West Coast pop art always was a poor relation to the world-beating New York original. Beside the Big Apple titans – Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and Claes Oldenburg – LA painters such as Ed Ruscha, Robert Irwin and John Altoon remained essentially local figures. Or that’s certainly the way it has looked from this side of the pond. Ruscha (pronounced to rhyme with touché) may now be acclaimed as one of America’s greatest living artists, but with this first major British retrospective, the 72-year-old artist still has a lot to prove here and a lot to tell us about an aspect of American art about which we’ve remained remarkably ignorant

While New York pop eschewed the autobiographical and the anecdotal, situating itself in a brutally mechanistic present in which it was forever 1962, Ruscha’s paintings with their abstracted gas stations and suburban homilies are tinged with a vernacular Americanness that remains ambiguous, but is born out of the artist’s own life experience. At 19 Ruscha left his home in Oklahoma City, driving along the mythic Route 66 to California to enrol in an art school sponsored by, of all people, Walt Disney. He studied graphic design and typesetting alongside fine art, and the interplay of words and images has remained a constant in his art over five decades. His deadpan disjunctions of sounds, appearances and meanings are never less than witty and occasionally laugh-out-loud funny

Oof from 1963 takes the kind of comic-book sound that Lichtenstein makes explicit in his images, and reduces it to a hermetic Zen abstraction of yellow letters on blue. In Hurting the Word Radio from 1964, the letters are squeezed with meticulously painted clamps in a way that does look weirdly painful. If these early works tells us little new about their period, they remain remarkably fresh. Indeed, such is the current influence of early pop and neo-Dada that these paintings might have been created by a thirty-something artist of today.

By 1966, Ruscha had hit on his best-known image, Standard Gas Station (pictured above), the building squeezed into a narrow diagonal perspective that has become in effect the artist's own logo; the word "Standard", both a brand name and a gnomic text in its own right.

By 1966, Ruscha had hit on his best-known image, Standard Gas Station (pictured above), the building squeezed into a narrow diagonal perspective that has become in effect the artist's own logo; the word "Standard", both a brand name and a gnomic text in its own right.

While exhibitions by contemporary artists tend to cultivate a distant, even anonymous feel, Ruscha’s droll pronouncements are used liberally throughout the exhibition. Of The LA County Museum of Art from 1965, which shows the then newly opened museum on fire, he says, "I knew at the time I started the picture I was going to assault that building somehow." Indeed, for all his conceptual canniness, Ruscha’s utterances have a quality of hickory-tinged folk wisdom: "The most an artist can do is start something and not give the whole story – that’s where mystery begins."

If some of his visual jokes are pat one-liners you don’t need to see to get the point – "It’s a Small World" is just a tiny globe floating in a void – his best work is imbued with a deeper sense of ambiguity. Cryptic phrases drawn from everyday life – Wen Out for Cigrets N Never Came Back or Japan is America – float over chocolate-box sunsets and LA nightscapes in his 1980s paintings: an effect that feels part sculptural, part cinematic. A later series of monochrome airbrushed paintings of archetypal American images – suburban houses, a New England church, a howling coyote – have an eerily numinous feel.

This is a hugely entertaining exhibition that achieves the rare feat of making you actually like the artist as a human being. And stripped of its usual cluttering screens, the Hayward has seldom looked better, its 1960s Brutalist architecture perfectly complementing the tongue-in-cheek alienation of Ruscha’s paintings.

In the final room his laconic cool reaches its apotheosis in clichéd images of the American sublime, vast mountainscapes that reduce into meaningless marks as you move closer, over which float blunt, quasi-commercial pronouncements: Baby Jet, Parking for House of Blues or simply The. The images are banal, the language almost drained of meaning, yet the effect is peculiarly and paradoxically transcendent.

GREAT POP ART RETROSPECTIVES

Allen Jones, Royal Academy. A brilliant painter derailed by an unfortunate obsession

Andy Warhol: The Portfolios, Dulwich Picture Gallery. An exhibition of still lifes which are anything but still

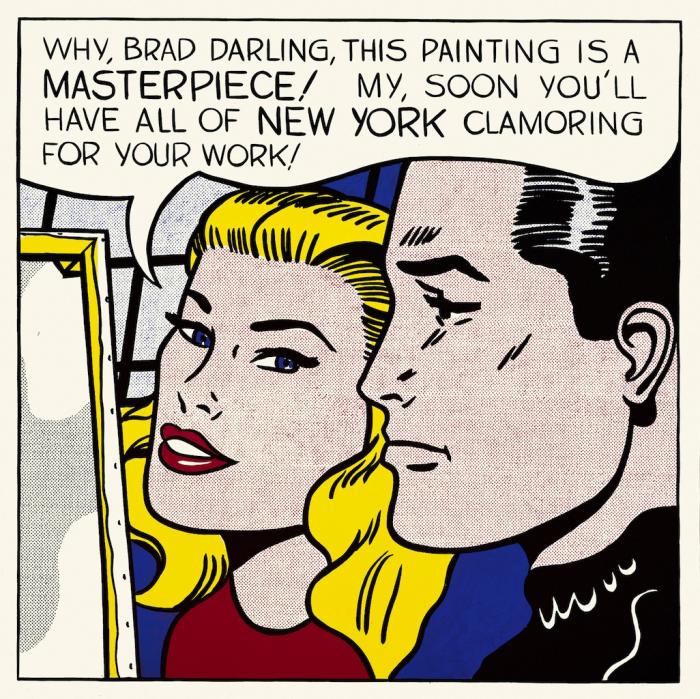

Lichtenstein: A Retrospective, Tate Modern. The heartbeat of Pop Art is given the art-historical credit as he deserves (pictured above, Lichtenstein's Masterpiece, 1962)

Lichtenstein: A Retrospective, Tate Modern. The heartbeat of Pop Art is given the art-historical credit as he deserves (pictured above, Lichtenstein's Masterpiece, 1962)

Patrick Caulfield, Tate Britain. A late 20th-century great emerges into the light

Pauline Boty: Pop Artist and Woman, Pallant House Gallery. The paintings are wonderful, but the curator does a huge disservice to this forgotten artist

Richard Hamilton, Tate Modern /ICA. At last, the British 'father of Pop art' gets the retrospective he deserves

Add comment