4 48 Psychosis, Royal Court review – powerful but déjà vu | reviews, news & interviews

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review – powerful but déjà vu

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review – powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s exceptionally groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

Sarah Kane is the most celebrated new writer of the 1990s. Her work is provocative and innovative. So it seems oddly unimaginative to mark the 25th anniversary of her final play, 4.48 Psychosis, by simply recreating the original production, with the original actors and the original production team in a joint Royal Court and Royal Shakespeare Company venture.

Sadly this is typical of our reboot culture, which prefers the old to the new, nostalgia over experiment, but it does feel like a wasted opportunity. After all, when David Byrne, artistic director of this venue, was head of the New Diorama Theatre, he staged a thrilling production of the same play, with Deafinitely Theatre’s all-male cast, a move which decisively challenged the idea that the work has to be performed mainly by women, and that it is, to use the prevailing cliché, a “suicide note”.

Of course it’s easy to see why 4.48 Psychosis has been given this headline-grabbing label. Kane completed it just before she took her own life, and the first production at the Royal Court in 2000 – now being mimicked – was posthumous. Of course, the play does deal with suicidal thoughts, mental disturbance and so on, although I would argue that a lot of the emotional fuel of the piece also comes from its passages about love, and about rejection by a loved one. Even a completely fantasy lover. I think this playwright’s writing defies over-simplification – there’s always a lot going on.  As a valediction, this play is a culmination of Kane’s quest to experiment in form and content, and to challenge the easy options offered by good old English naturalism, where what you see is what you get. And that’s all you get. Given its title, which suggests extreme anguish and refers to waking up in the middle of the night, Kane approaches her themes by radically questioning the structure of ordinary drama. So 4.48 Psychosis has no named characters, no specified setting, no actual plot and no stage directions. Instead, on the page it looks like a modernist poem, a refugee from the pages of TS Eliot or even Dada, an open text which is so free that it can be performed as a monologue, or by three actors or by 30.

As a valediction, this play is a culmination of Kane’s quest to experiment in form and content, and to challenge the easy options offered by good old English naturalism, where what you see is what you get. And that’s all you get. Given its title, which suggests extreme anguish and refers to waking up in the middle of the night, Kane approaches her themes by radically questioning the structure of ordinary drama. So 4.48 Psychosis has no named characters, no specified setting, no actual plot and no stage directions. Instead, on the page it looks like a modernist poem, a refugee from the pages of TS Eliot or even Dada, an open text which is so free that it can be performed as a monologue, or by three actors or by 30.

What’s the text about? Well, in a series of jagged fragments, it describes mental distress, feelings of fault and shame, medical intervention and its rejection, despair, depression and disgust. The sensation of being utterly alone. Inside your head. The piece is composed of several voices, which run through a checklist of symptoms, a litany of drug treatments and their results, a conversation about self-harming, a list of life goals. Acute desperation is shown, and always the running theme of unrequited love, feelings of rejection. There are short passages of fine writing, internal monologues, psychiatric questionnaires, lists of numbers and small blazes of spirituality. The dark glory of “Remember the light and believe the light” recurs through the play.

Just as the word “psychosis” means losing contact with reality, suffering a splintering of the world, so the form of Kane’s masterpiece is splintered, a patchwork of diverse styles. Here the notion of mental collapse is both real and a metaphor for anything, from passionate love to sudden death, that turns our lives upside down. Despite the intensity of some of this material, there are lighter bits, Kane’s trademark being dark humour. For my taste, there are too many Eng Lit references, overblown stuff about cockroaches, cold black ponds, and mind-numbing punky declarations such as “We are anathema/ the pariahs of reason” or “fuck you God”. All a bit too juvenile.

In other passages, there’s both the lucid confusion of the most despairing of the depressed, and explosions of rage, rage, rage. Most disturbing is the suggestion that the mentally ill embrace their condition, defend their identity as incurable, rejecting treatment as a badge of pride. Being suicidal is a role played — by the suicidal. Exaggerated. Then there are moving bits about friends and friendlessness, about sympathetic doctors and unsympathetic ones. And about the desire for love, but also for freedom. Religious thoughts next to bleak jokes. The hallmarks are extreme subjectivity and solipsism.

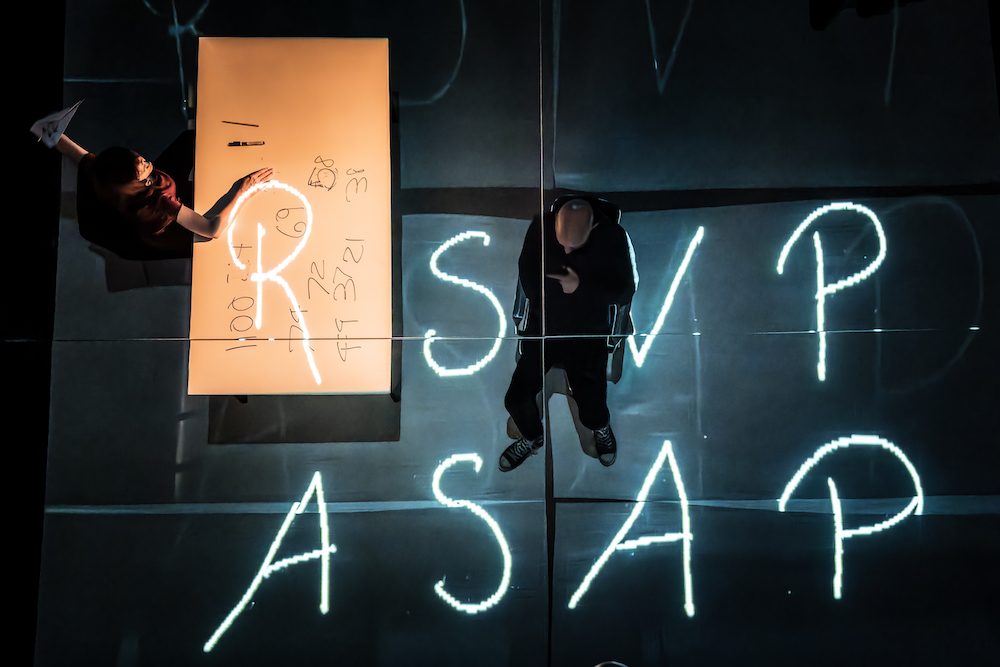

Reprising their roles from 25 years ago, Daniel Evans, Jo McInnes and Madeleine Potter explore the sensibility of the 70-minute play’s agonized self-consciousness: “It is myself I have never met, whose face is pasted on the underside of my mind.” Compared to the original production, they are more controlled and more choral, more focused. Director James Macdonald and designer Jeremy Herbert return to their original design of bare white stage with large mirror, plus projections of street scenes (video by Ben Walden), static and occasional text (pictured above) to emphasize the disjunction of the inner life from external reality.

This is almost identical to the original production, also staged in the claustrophobic Theatre Upstairs. I remember this memorial performance on Saturday, 24 June 2000. The atmosphere was funereal, an air of reverence. The show began with a long agonizing silence – broken by a mobile phone. As its owner struggled to silence it, Vince O’Connell (Kane’s mentor and friend since her teenage years) let out a long growl: “Arseholes”. After this tribune to Kane’s no-nonsense personality, the performance did succeed in honouring the play’s dark humour as well as its moments of spiritual awe. At the end, a window was opened and sounds from the summer street outside floated into the theatre, a reminder that whatever happens inside your head, life flows on regardless.

This current reboot, which remains powerful enough to leave me shaken, also seals the play in the aspic of commemoration. It’s a poor choice for this venue, which has a reputation for radical innovation rather than nostalgic repetition. Not only are the cast arguably now too old for such a young person’s play – Kane was 28 when she killed herself – but it’s depressing that they are all white: isn’t it time that contemporary classics were staged with at least some non-white actors? Still, for those new to Kane this restaged production does offer a kind of definitive experience: I only hope it will inspire challenges from other theatre-makers, as well as new and innovative explorations of her work.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review – powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s exceptionally groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review – powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s exceptionally groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

Joyceana around Bloomsday, Dublin review - flawless adaptations of great dramatic writing

Chapters and scenes from 'Ulysses', 'Dubliners' and a children’s story vividly done

Joyceana around Bloomsday, Dublin review - flawless adaptations of great dramatic writing

Chapters and scenes from 'Ulysses', 'Dubliners' and a children’s story vividly done

Stereophonic, Duke of York's Theatre review - rich slice of creative life delivered by a 1970s rock band

David Adjmi's clever and compelling hit play gets a crack London cast

Stereophonic, Duke of York's Theatre review - rich slice of creative life delivered by a 1970s rock band

David Adjmi's clever and compelling hit play gets a crack London cast

North by Northwest, Alexandra Palace review - Hitchcock adaptation fails to fly

Emma Rice's storytelling at fault in misconceived production

North by Northwest, Alexandra Palace review - Hitchcock adaptation fails to fly

Emma Rice's storytelling at fault in misconceived production

Hamlet Hail to the Thief, RSC, Stratford review - Radiohead mark the Bard's card

An innovative take on a familiar play succeeds far more often than it fails

Hamlet Hail to the Thief, RSC, Stratford review - Radiohead mark the Bard's card

An innovative take on a familiar play succeeds far more often than it fails

The King of Pangea, King's Head Theatre review - grief and hope, but no connection

Heart and soul proves insufficient in world premiere of therapeutic show

The King of Pangea, King's Head Theatre review - grief and hope, but no connection

Heart and soul proves insufficient in world premiere of therapeutic show

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Bridge Theatre review - Nick Hytner's hit gender-bender returns refreshed

This Dream is a great night out, especially for Shakespeare first-timers

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Bridge Theatre review - Nick Hytner's hit gender-bender returns refreshed

This Dream is a great night out, especially for Shakespeare first-timers

Miss Myrtle’s Garden, Bush Theatre review - flowering talent, but needs weeding

New play about loss, love, grief and gardening is humane, but flawed

Miss Myrtle’s Garden, Bush Theatre review - flowering talent, but needs weeding

New play about loss, love, grief and gardening is humane, but flawed

Fiddler on the Roof, Barbican review - lean, muscular delivery ensures that every emotion rings true

This transfer from Regent's Park Open Air Theatre sustains its magic

Fiddler on the Roof, Barbican review - lean, muscular delivery ensures that every emotion rings true

This transfer from Regent's Park Open Air Theatre sustains its magic

In Praise of Love, Orange Tree Theatre review - subdued production of Rattigan's study of loving concealment

Unspoken emotion flows through this late work

In Praise of Love, Orange Tree Theatre review - subdued production of Rattigan's study of loving concealment

Unspoken emotion flows through this late work

Letters from Max, Hampstead Theatre review - inventively staged tale of two friends fighting loss with poetry

Sarah Ruhl turns her bond with a student into a lesson in how to love

Letters from Max, Hampstead Theatre review - inventively staged tale of two friends fighting loss with poetry

Sarah Ruhl turns her bond with a student into a lesson in how to love

Elephant, Menier Chocolate Factory review - subtle, humorous exploration of racial identity and music

Story of self-discovery through playing the piano resounds in Anoushka Lucas's solo show

Elephant, Menier Chocolate Factory review - subtle, humorous exploration of racial identity and music

Story of self-discovery through playing the piano resounds in Anoushka Lucas's solo show

Add comment