Q&A: Playwright Nick Dear on Adapting Frankenstein | reviews, news & interviews

Q&A: Playwright Nick Dear on Adapting Frankenstein

Q&A: Playwright Nick Dear on Adapting Frankenstein

The man who lured Danny Boyle back to the stage answers the critics' questions

It is one of the most hotly anticipated new productions at the National Theatre in years, for which all but day seats have long since been sold out. Danny Boyle has been lured back to the stage to direct a version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

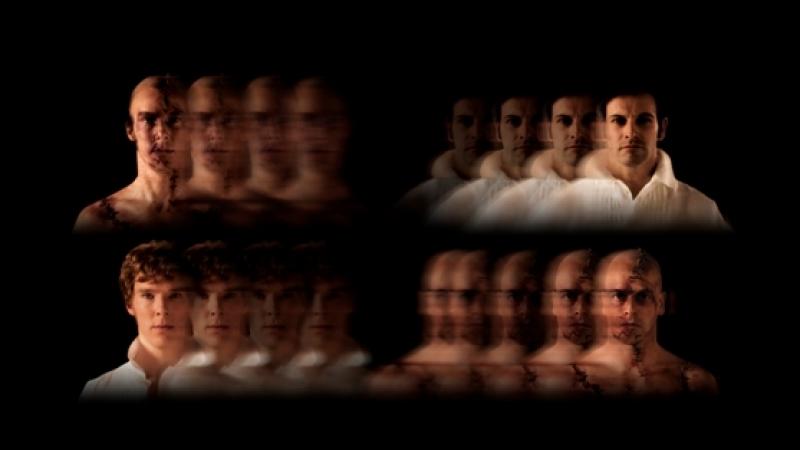

It is one of the most hotly anticipated new productions at the National Theatre in years, for which all but day seats have long since been sold out. Danny Boyle has been lured back to the stage to direct a version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. In a rare and daring instance of double casting, Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller will share the duties of playing Victor Frankenstein and the creature which, in popular mythology, has taken his name. NT Live will thus be screening two separate performances. But in the first instance, the names which will make the box office tick over can do nothing without an adaptation. The task of going into the laboratory to create the theatrical facsimile of a novel subtitled A Modern Prometheus has fallen to the playwright Nick Dear.

In Frankenstein, Dear returns to the theme of fulminating creativity. For the theatre he has written about Hogarth in The Art of Success (1986) and the life of Chekhov in Summerfolk (1999). He is also a regular visitor to the crucible of the Romantic Age. Among his television dramas, his two-part Byron (2003) featured a compelling performance from Miller, while in the same year came Eroica, his dramatisation of the creation of Beethoven’s third symphony. He also adapted the first and, for some, still the finest of the long run of Jane Austen novels for the screen with Persuasion (1995). "Curious fact," says Dear: "Persuasion was published in the same month as Frankenstein."

Four of theartsdesk's theatre writers were each asked to address a couple of questions to Nick Dear on different aspects of adapting Frankenstein.

MATT WOLF: What do you think of the Branagh film? Did the story’s film history come up in discussion with Danny Boyle, and if so how?

NICK DEAR: We would have made this show a lot earlier had it not been for Branagh’s film! Danny and I were working on a stage version of Frankenstein in the early Nineties; we shelved it when Branagh’s version came out. What I think of that is not important here. We didn’t really reference any of the movies, except as examples of things we didn’t want to do – eg no bolt through the neck, no hunchbacked assistant, no slab. Perhaps no Robert de Niro (model of De Niro's make-up pictured right). Mainly I concentrated on the book. Although the story has of necessity had to be trimmed, and I have re-shaped it somewhat, the ambition has always been to express the spirit of Mary Shelley’s novel of ideas as faithfully as possible.

NICK DEAR: We would have made this show a lot earlier had it not been for Branagh’s film! Danny and I were working on a stage version of Frankenstein in the early Nineties; we shelved it when Branagh’s version came out. What I think of that is not important here. We didn’t really reference any of the movies, except as examples of things we didn’t want to do – eg no bolt through the neck, no hunchbacked assistant, no slab. Perhaps no Robert de Niro (model of De Niro's make-up pictured right). Mainly I concentrated on the book. Although the story has of necessity had to be trimmed, and I have re-shaped it somewhat, the ambition has always been to express the spirit of Mary Shelley’s novel of ideas as faithfully as possible.

MATT WOLF: Such diverse and disparate plays as Richard II and Sam Shepard's True West have gone the changing-roles route. What are the advantages/disadvantages? Matthew Warchus said it was very tricky with True West because one Austin would hear laughs (although in Frankenstein’s case it would be shrieks) garnered by Lee that weren't there when the roles were reversed. Is there a comparable danger with this?

We don’t really know how the switch-around will work, as we haven’t put it before an audience yet. The two guys seem to be enjoying the challenge; they each sit in on the other’s rehearsals. What’s interesting is that it doesn’t allow the actor to become possessive of their character. It’s not unusual for an actor to see a play entirely from his/her character’s point of view. But in this case the two actors are forced constantly to experience the whole play – usually only the writer and director do this, and of course the audience. Will that make a difference? We’ll find out.

It’s a rewarding idea for this particular project because there are so many elements of the Doppelgänger in the original story. Victor Frankenstein is a narcissist – when he comes to create a man, he tries to do so in the image of himself. He fails, but only because his technology isn’t up to the task. And then, as any father does, he finds elements of himself in his "child".

My two characters, Victor and The Creature, reflect and complement each other, and we can only hope that the double casting will yield a rich interpretation from the actors playing them. They’re such good actors that seeing the show either way round should be fun. The double casting is also useful as an announcement to the audience that we are working here on a human scale: it’s the theatre, not the movies, and our actors are not computer-generated or otherwise enhanced. In other words, expect the power of the story to be what is scary, rather than slasher-movie prosthetics.

ALEXANDRA COGHLAN: This is a story by a woman. It is easy to forget that remarkable fact. How conscious were you when adapting it that Frankenstein represents an important step in the development of the Female Gothic. Did you put it out of your mind, and if so why? Or is it possible to retain this gendered narrative element in a stage adaptation?

ALEXANDRA COGHLAN: This is a story by a woman. It is easy to forget that remarkable fact. How conscious were you when adapting it that Frankenstein represents an important step in the development of the Female Gothic. Did you put it out of your mind, and if so why? Or is it possible to retain this gendered narrative element in a stage adaptation?

No, I never forgot that it’s a story written by a woman who was only 18 when she started it. But she didn’t know she was taking an important step in the development of the Female Gothic, and I tend to dismiss such academic concerns as not really pertinent to the job I do. It’s not a question of putting it out of my mind; it’s just that it doesn’t help very much. In fact it can actively stop you writing! How do you think that appreciating the development of the Female Gothic is likely to help me write a good character? It might help me write a good essay, but that’s not my territory.

On the other hand, the abiding presence of Mary Shelley’s dead mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, hovers over every page. But the feminism that her very name suggests does not really manifest itself in the book. Many stage and film versions of the story have helicoptered in the character of Mary Shelley herself as a replacement for Elizabeth, Victor’s fiancée, whose feminist leanings are hidden under a very large bushel. I decided that I’d save writing about Mary Shelley herself for another time, and concentrate on Elizabeth, who with a little help might be persuaded to grow into an interesting character. Yet the fact remains that her great ambition is to marry Victor and have lots of children – unlike her creatrix, she is no bohemian fellow traveller, she is quite at home embroidering at the bourgeois hearth.

Look, the three narrators in the book are male. The essential plot is one of two men, or one man and an almost-man. The subject matter seems to me "universal". Every dramatist makes choices as to how they will adapt something, and perhaps those choices are influenced by gender, or perhaps they aren’t. But, without wishing to sound entirely reactionary, a task at which I usually fail, these questions are never asked when women adapt books written by men. Either everything is a gendered narrative, or nothing is.

I found a lot of feminist criticism, for example the work of Anne Mellor, very useful in trying properly to understand the book. A raft of ideas, especially regarding the relationship of pregnancy and birth to the story, and particularly Mary Shelley’s experience of it, might not have occurred to me otherwise.

ALEXANDRA COGHLAN: How are you going to address the narrative frame with its letters and reported action?

Easy. I’ve cut it.

Watch a clip of the first ever Frankenstein film, from 1912

JAMES WOODALL: The last line of The Art of Success has Fielding saying something like, "I'm off to invent something: it's called the novel." Is there in your view an intrinsic relationship between novel and playwriting/ a novel and a play, or are the forms mutually exclusive?

I think they’re pretty exclusive. Most novelists think writing plays is easy, leading to the excruciatingly embarrassing chapters one sometimes finds in the middle of novels where they decide to have a go at "dialogue" form. And although most playwrights spend a lot of work-avoidance time dreaming of writing novels, we don’t usually get around to it, daunted – I suspect – by the thought of all those words. Henry Fielding was a very particular example, as it was overt and specific state censorship which curtailed his playwriting career. He had no choice but to try a new form, which we might see as a happy accident, since his novels are fab and his plays… not often revived. However, dramatists are always hungry for the fresh meat of good stories, and have always plundered other formats shamelessly for them. In making a play out of Frankenstein I’m only doing what Shakespeare often did – purloining someone else’s story. And there the comparison ends. (But at least I acknowledge my sources.)

The most significant difference between plays and novels seems to me that novels operate in the past. They both are, and are about, things which have happened – whereas plays operate in a kind of continuous present, due to the requirement that living actors must perform them in front of us. There isn’t really a past tense in a play. And although a novel can be written in the present tense, the actuality of the thing which you hold in your hand is that it was made in the past, not now. This isn’t a value judgement, just an observation of difference.

I think that to create and activate an authentic-seeming world on a stage is a different skill from creating an authentic-seeming world in the mind of a reader, and very few writers are good at both. Does anyone read Henry James’s plays?

JAMES WOODALL: Your works have very specific historical settings, with these amazing figures - Hogarth, Zenobia, Louis XIV - navigating treacherous waters; Frankenstein also has a clear historical hinterland, though is of course fictional. To what extent do you feel you need these contexts, and these huge characters, to fire your dramas?

Um, I have been known to write about the quotidian realities of South London but to date have been unable to find a producer for these outpourings. I think need may be a little strong, but I do seem to respond to big narratives, larger-than-life figures, extreme events, unusual predicaments. They just seem to me to offer dramatic possibilities in a way that daily life doesn’t – although someone like the brilliant Tony Marchant seems well able to find them there, which suggests I may need to get out more. Also I like intriguing costumes, colour on a set, worlds apart, strange horizons. I like the idea that for two or three hours we inhabit a different universe. And then I like to go home. I may change tack one day. Ibsen did, to great benefit.

SAM MARLOWE: The main point that strikes me about Frankenstein is that despite Branagh's more faithful film version, most people still associate the monster with Boris Karloff (and some even still think Frankenstein is the monster's name rather than his creator's). Does that feel like a powerful mythology to take on – especially since anyone expecting creepy thrills and delving into the book quickly discovers that it's a tough and sometimes pretty plodding read?

Well, I hope and trust I’ve cut most of the plodding bits. I don’t think a book written 200 years ago is mythology, exactly – but I do think it is a kind of fairy tale, a fairy tale for grown-ups. It still has wonderful resonance: whereas Jane Austen looks back over the previous century, manners and marriage, Mary Shelley – only about 20 years younger – looks forward to the coming century, the machine age, the death of God, the humanist revolution. And the moral questions she airs – about parental responsibility, scientific progress, difference and otherness, what it means to be human – will I hope feed into an evening in the theatre which is characterised more by questing intelligence than by creepy thrills. Neither Danny Boyle nor myself are interested in creepy thrills for their own sake. Hammer Horror it ain’t.

Well, I hope and trust I’ve cut most of the plodding bits. I don’t think a book written 200 years ago is mythology, exactly – but I do think it is a kind of fairy tale, a fairy tale for grown-ups. It still has wonderful resonance: whereas Jane Austen looks back over the previous century, manners and marriage, Mary Shelley – only about 20 years younger – looks forward to the coming century, the machine age, the death of God, the humanist revolution. And the moral questions she airs – about parental responsibility, scientific progress, difference and otherness, what it means to be human – will I hope feed into an evening in the theatre which is characterised more by questing intelligence than by creepy thrills. Neither Danny Boyle nor myself are interested in creepy thrills for their own sake. Hammer Horror it ain’t.

SAM MARLOWE: Are you aware of or have you seen any previous stage versions? One I saw in Northampton in 2008, adapted by Lisa Evans, featured a framing device in which a woman (Mary) accused of murdering her baby, wandered around a modern psychiatric ward, poring obsessively over Shelley's novel. It was a collaboration with Frantic Assembly that attempted to integrate stylised movement. Does your version allow for any particular theatrical/visual techniques to animate the prose? Have you introduced any "concept" or adjustment that gives the text 21st-century immediacy?

The only other stage version I know is Liz Lochead’s lovely Blood and Ice, but that – again – introduces the historical characters (Byron et al) into the novel, which I was determined not to do. I haven’t seen any of the more recent ones, perhaps as a result of not getting out enough. I don’t animate the prose at all - I just ditch it altogether. And although we experimented, over the years, with framing concepts, in the end we ditched them too. I have refocused the narrative for specific reasons, but the tale we tell is very much Mary Shelley’s, set roughly in period, and not deviating in any major way from her central narrative. Whether it has 21st-century immediacy is for you all to judge.

- Frankenstein will be shown in cinemas twice by National Theatre Live. Benedict Cumberbatch as the Creature and Jonny Lee Miller as Frankenstein can be seen on 17 March. The roles will be reversed on 24 March, also at 7.00pm (with worldwide screenings at a later date)

- Frankenstein at the National Theatre is sold out until 17 April. Day seats are available

- Find Mary Shelley's Frankenstein on Amazon

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Interview, Riverside Studios review - old media vs new in sparky scrap between generations

Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes make worthy sparring partners

Interview, Riverside Studios review - old media vs new in sparky scrap between generations

Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes make worthy sparring partners

Fat Ham, RSC, Stratford review - it's Hamlet Jim, but not as we know it

An entertaining, positive and contemporary blast!

Fat Ham, RSC, Stratford review - it's Hamlet Jim, but not as we know it

An entertaining, positive and contemporary blast!

Juniper Blood, Donmar Warehouse review - where ideas and ideals rule the roost

Mike Bartlett’s new state-of-the-agricultural-nation play is beautifully performed

Juniper Blood, Donmar Warehouse review - where ideas and ideals rule the roost

Mike Bartlett’s new state-of-the-agricultural-nation play is beautifully performed

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

Add comment