Frankenstein, National Theatre at Home review – creature discomforts | reviews, news & interviews

Frankenstein, National Theatre at Home review – creature discomforts

Frankenstein, National Theatre at Home review – creature discomforts

NT Live version of this iconic tale of creative hubris features a dynamic acting duo

So far, it could be said that the National Theatre is having a good lockdown. Every week, this flagship streams one of its stock of NT Live films, which are always a welcome reminder of the range of its output over the past decade or so.

The familiar story is told with great rapidity: Victor Frankenstein, an ambitious scholar-scientist, creates a creature out of body parts and manages to reanimate it. Appalled by its monstrous appearance, he throws his creation out of the house. Alone in the world, the creature inspires horror in all who meet him, and only finds peace when he finds a kind old blind man in a remote forest. Here he acquires an education, symbolically following Shelley’s original invocation of Milton’s Paradise Lost, and then conceives of a desire for a mate. He travels to Geneva to demand that Frankenstein build him a female, just as the scientist is about to marry his adopted sister Elizabeth. Events stumble to a brutal conclusion.

Dear and Boyle’s version recounts events from the point of view of the nameless creature. It starts not with Frankenstein and his hunchback helper setting up in a laboratory, in the middle of a lightning-laced thunderstorm, but with the birth of the creature, in a kind of placenta-ripping sequence in which first his hand and then his finger pushes against a membrane, which splits, allowing him to emerge into the world naked, like Adam (although a blush-sparing loin cloth is used here). Following this elemental creation, he moves into society and we witness his rejection by prejudiced people, until he finally finds temporary solace with the blind man in his isolated hut. So when he meets Frankenstein again we see their relationship from the perspective of an outsider.

Our sympathy is with the creature, and the story emphasizes the destructive consequences of not knowing your name, of being solitary and of being unloved. The creature’s violence comes from his ill treatment. On Frankenstein’s side, the picture is mixed: clearly, he has acted irresponsibly in making a being who he doesn’t care for, and there is more than one exchange when Elizabeth points out that he shouldn’t play God, but rather take his family responsibility by becoming a father. Trouble is, he is obsessed with science and not much interested in love. He never even touches her. Like anyone who has made a truly tragic mistake, the story is also about his desperate efforts to put things right.

Dear has thankfully eliminated some of the original story’s complexity, and this version powerfully shows how both Frankenstein and his creation are two sides of the masculine self; one is rational and cerebral, the other sensuous and full of feeling. The antagonism between the two, which focuses on the creature’s intense desire for a wife, is the conflict between vaulting intellectual ambition and a more grounded bodily happiness. Nurture and nature struggle together. Care and control fight it out. In the end, it is no spoiler to note that both scientist and creature are locked together in an eternal embrace. Paradise has been well and truly lost.

Dear has thankfully eliminated some of the original story’s complexity, and this version powerfully shows how both Frankenstein and his creation are two sides of the masculine self; one is rational and cerebral, the other sensuous and full of feeling. The antagonism between the two, which focuses on the creature’s intense desire for a wife, is the conflict between vaulting intellectual ambition and a more grounded bodily happiness. Nurture and nature struggle together. Care and control fight it out. In the end, it is no spoiler to note that both scientist and creature are locked together in an eternal embrace. Paradise has been well and truly lost.

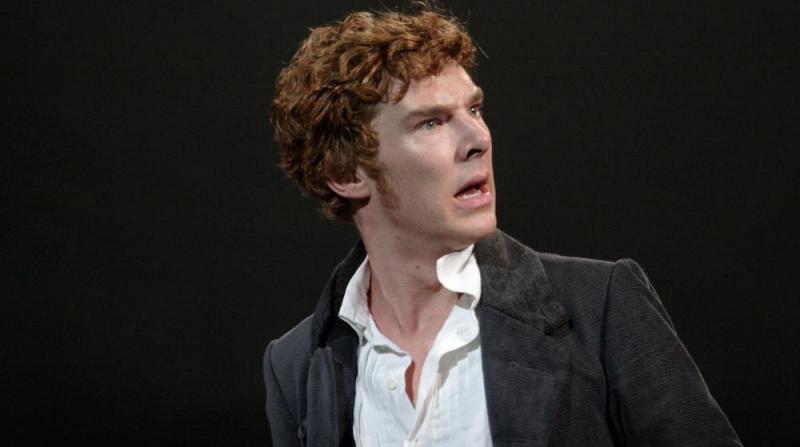

The production’s double casting allows us, especially in the close ups of Tim van Someren’s thrillingly filmed version, to savour two strong performances. Cumberbatch’s creature is a mesmerizing creation, at first uncomfortably jerky, then gradually being educated into humanity and finally astonishing us by his eloquent plea for love. His anger is scalding, and his energy is palpable, although some might accuse him of over-acting. As Frankenstein, by contrast, he is both icy and frantic. Miller’s interpretation is less detailed, but perfectly carries a brute panting force as the creature (pictured above) and a confident arrogance as Frankenstein. Both actors are at their best in their passionate advocacy of social transgression and intellectual creativity. But my preference is for Miller as the creature and Cumberbatch as Frankenstein.

By itself double casting suggests the story’s doppelgänger theme in what is essentially a fairy tale for grown-ups. With its aerial shots, hazy passages and delight in splashes of light, shots of a myriad glowing bulbs and red then phosphorous-blinding moments, this filmed record is enjoyable and occasionally almost enchanting. For example, the creature’s early pleasure in childlike joy, amazed by the dawn, or a flight of birds, bathed by rain and thrilled by falling snow. But the film also cruelly exposes Dear’s writing, which is often banal and lacks both subtext and ideas. Infuriatingly, there’s not a trace of Shelley’s profundity, and the quotations from Milton only point up the thinness of the text, despite its numerous references to Adam and Eve.

Likewise, Boyle’s directing is by no means flawless. At its best, there’s sense of a ranging imagination, greatly aided by designer Mark Tidesley and especially Bruno Poet’s superb lighting. But too often the staging is static and so lacking in dynamism that you are forced to reassess the director’s awesome reputation. In many passages the show lacks visual stimulation, and Underworld’s electronic music rarely galvanizes the emotions. It’s all a bit clumsy. Exceptional moments, like the birthing and the arrival of the metaphorical industrial age train, or the creature’s dream of a mate, are just that — exceptions. Apart from the dynamic duo, the rest of the cast, such as Naomie Harris’s Elizabeth, is under-used. Despite some flashes of resonance, as when Frankenstein claims he can cure any sickness, this show is not uniformly brilliant.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment