Serge Gainsbourg vs The Anglo-Saxons | reviews, news & interviews

Serge Gainsbourg vs The Anglo-Saxons

Serge Gainsbourg vs The Anglo-Saxons

How a louche French national treasure became an international cult

The arrival of Gainsbourg: Vie Héroique in British cinemas this week – under its Anglo-Saxon title Gainsbourg – assumes that distributors think there’s an audience. Even so, Gainsbourg hardly has the appeal of a Johnny Cash biopic. Or even an Ike Turner biopic.

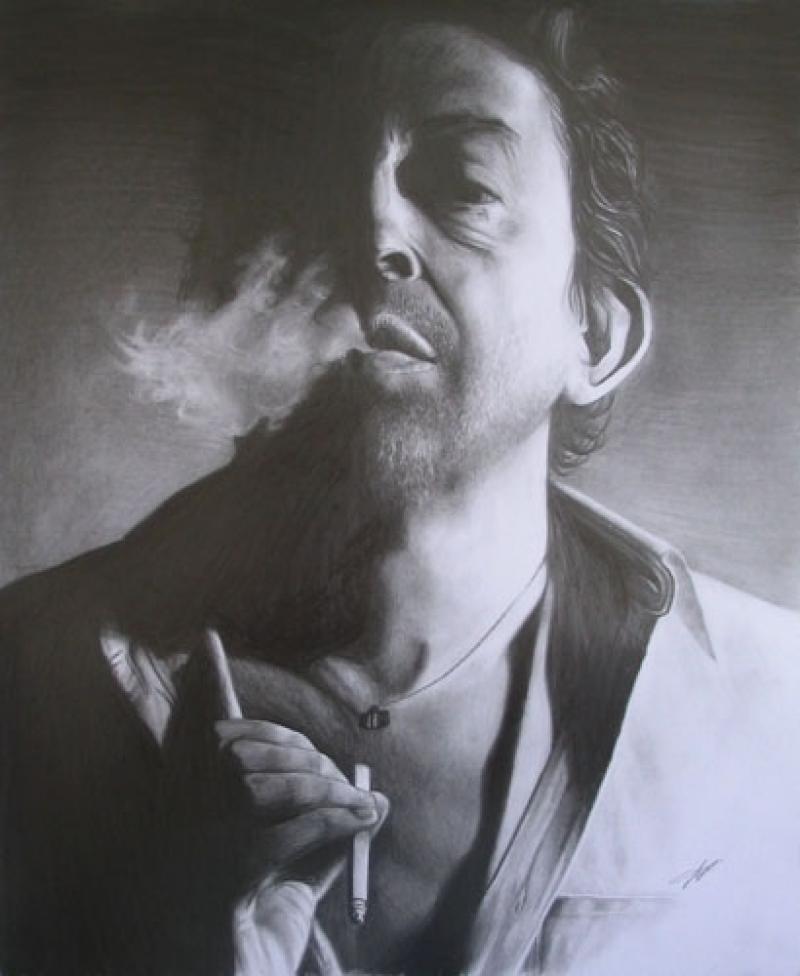

Which means that the film’s ads gloss over the music and cultural context to play up the man with the cabbage head’s liaisons with Bardot, Birkin and the rest. Most coverage is content to tag along with stereotypical ideas of Gainsbourg as a big-nosed, besuited Casanova. It’s as if Eric Elmosnino’s remarkable channelling of the persona is about the louche, constant fag-in-mouth cliché of Gainsbourg as the cipher for a type of French manhood irresistible to les femmes.

But this is just part of it. Serge Gainsbourg is a national monument in France, a Baudelaire, a Chopin – a buffoonish provocateur too. This is the vie héroique the film celebrates. His death brought France to a standstill in 1991, but for the English-speaking world he was barely heard of until the mid-Nineties. Before that, any discussion centred on his only British hit, 1969’s “Je t’aime…moi non plus”. And most mentions of that record were confined to its banning and the temperature-raising performance of his muse Jane Birkin. A classic one-hit wonder, and after its success Gainsbourg was pretty much forgotten.

Yet Gainsbourg was well known within the British music business. He regularly recorded in London, with legendary arrangers/ producers like Arthur Greenslade in the 1960s and Alan Hawkshaw in the Seventies. 1975’s Rock Around the Bunker album featured the voice of Clare Torrey, recognised world wide from Pink Floyd’s “Great Gig in the Sky”. She’s the one chirping “Nazi rock, Nazi rock". It’s an odd world where a session singer is more prominent than the artist.

The first hint of a new Anglo-Saxon awareness of Gainsbourg came in 1987 when The Bollock Brothers (featuring John Lydon’s brother, Jimmy) issued a version of “Harley Davidson”. But that one-off was an eccentric expedition into largely unknown territory. Gainsbourg’s infiltration of non-French music really began in 1991 – the year of his death – with two albums from disparate, but equally adventurous, artists. De La Soul’s second album, De La Soul is Dead, featured samples from Melody Nelson, while the entire sonic palette of My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless was borrowed from “Bonnie and Clyde”.

"Ballade de Melody Nelson" by Portishead feat. Jane Birkin, on YouTube

{youtube}Hs1zM6vOyEk {/youtube}

After these pioneers set their stall, the doors fell open in 1994-5. Portishead remixed Massive Attack’s “Karmacoma” in 1994 with a dollop of Melody Nelson (see video of Portishead and Jane Birkin, above) and Mick Harvey of Nick Cave’s Bad Seeds issued his Intoxicated Man album in 1995 (see video below). A collection of straight English-language Gainsbourg covers with sensitively translated lyrics, Intoxicated Man proved so successful that Harvey followed it up in 1997 with Pink Elephants, another all-Gainsbourg set.

Mick Harvey's "Intoxicated Man" on YouTube

1995 was a busy year for the newly Gainsbourg-obsessed as it also saw Shaun Ryder’s Black Grape release their first long-player, It’s Great When You’re Straight….Yeah. The track “A Big Day in the North” liberally sampled “Initials B B” (see Gainsbourg's original version below). That year also found Stereolab’s Laetitia Sadier joining New Yorkers Luna on their cover of “Bonnie and Clyde”. The mid-Nineties Gainsbourg fest continued in 1996 with David Holmes’s Let’s Get Killed album, which featured yet more Melody Nelson samples on “Don’t Die Just Yet”. Then John Zorn produced the Gainsbourg-themed Great Jewish Music compilation in 1997, with covers by Sean Lennon and Faith No More’s Mike Patton.

Serge Gainsbourg's "Initials B B" on YouTube

But why was Gainsbourg so attractive to these cutting-edge acts in the mid-Nineties? St Etienne’s Bob Stanley suggests it followed an evolution in British pop, signalled by the rise of stylish frontmen like Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker and Suede’s Brett Anderson – both, like Gainsbourg, performers with an unconventionally individual take on how pop singers should look and act.

“After Jarvis and Brett, Gainsbourg suddenly made more sense here,” says Bob. “Both were always fans. The crumpled pin-stripe suit look is always very now, and was very modern in the mid-Nineties. Before that, no one talked about Gainsbourg’s 1970s records. I remember Lawrence from Felt playing "L’Homme a tête de chou" in about 1990 and I thought he was being deliberately obscure. Back then you knew about "Torrey Canyon" and the France Gall records from the 1960s, but not Melody Nelson. Suddenly in the mid-Nineties everyone knew the Whitney Houston story.”

Watch a drunk Gainsbourg propositioning Whitney Houston on YouTube

For me, hearing Gainsbourg and Bardot’s duet “Bonnie and Clyde” (see video, below) was the epiphany. It was around 1994. I’d bought a load of French records in the Netherlands. Most were amazing – Jacques Dutronc, Michel Polnareff, Antoine. But “Bonnie and Clyde” was extra-terrestrial. You could hear chanson, Dylan, The Stones, The Beach Boys in those others, but atmospherically all “Bonnie And Clyde” related to was Lee Hazelwood’s “Some Velvet Morning”. Suddenly, I understood “Bonnie and Clyde”'s influence on My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless, the early-Nineties’ über-coolest indie album. Then I heard 1972’s Histoire de Melody Nelson. Its sparse mix of bass and drums was as radical as Can’s Tago Mago, yet there were strings, tunes, that brooding atmosphere and the peculiar story. Gainsbourg was obviously a powerful force.

Gainsbourg and Brigitte Bardot sing "Bonnie and Clyde", on YouTube

As I found out more, I learnt that in France Gainsbourg was as significant as Bowie, as provocative as The Sex Pistols, but with a wider cultural profile than both. He existed in a mainstream world. I bought Giles Verlant’s biography. Fired up, I saw Jane Birkin at Paris’s L’Olympia in October 1996 and couldn’t believe the audience: old people, children and everyone in between. No trendies. Gainsbourg’s music really did mean something to all France.

At home, it was clear I wasn’t alone. 1999 saw the publication of the first English-language biography, View From the Exterior by Alan Clayson. Although terrible, the publishers had identified a market. Sylvie Simmons redressed the balance in 2001 with A Fistful of Gitanes, a fine English-language biography that properly served the legend.

And the interest thrived. Beck eventually caught on and pilfered Melody Nelson in 2002 on Sea Change’s “Paper Tiger”. Just listen to the opening cut from the Super Furry Animals’ 2005 Lovecraft album, which echoes the arrangements of Gainsbourg’s collaborator Jean-Claude Vannier.

Vannier himself was disinterred to conduct a late 2006 first-ever live run through of the entire Histoire de Melody Nelson with the album’s original British session musicians at London’s Barbican. Cheerleaders Jarvis Cocker, Mick Harvey, the Super Furry Animals’ Gruff Rhys and Laetitia Sadier took turns on vocals. Jarvis also worked with Gainsbourg’s daughter Charlotte, writing lyrics for her 2006 album 5.55. Beck took the chance more recently, conjuring up her IRM album. For some artists, the chance to actually be Gainsbourg is irresistible.

Bob Stanley is sure Gainsbourg’s increased profile has had a significant effect, and not just on pop singers: “Even though he’s dead, Gainsbourg has single-handedly opened up people’s minds to foreign-language records over here. The interest in Tropicalia wouldn’t have happened without Gainsbourg having become relatively mainstream first. It’s been taken away from record collectors, the CDs and DVDs are now in the shops. So it’s not a fashion thing now, it’s an awareness thing. For some 15-year-old forming a new band, Gainsbourg will be another thing to take on board, another one of all the possible influences. Fifteen years ago it wasn’t like that. Everyone can hear Gainsbourg now.”

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Add comment