Michael Powell fell in love with his celluloid mistress in 1921 when he was 16. It’s a love affair that he’s conducted for 65 years. At 81, he’s not stopped dreaming of getting behind the camera again. At Cannes this year he hinted at plans to make a silent horror film, but he’s reluctant to talk about it.

I met Powell in his club, accompanied by his son Columba. It’s quite an uncanny experience seeing the two of them together in real life, so clearly warm and comfortable with each other. I’m familiar with them onscreen in Peeping Tom, made in 1960 when Columba was a child. He took the role of Mark Lewis (the protagonist played by Carl Boehm) as a little boy.

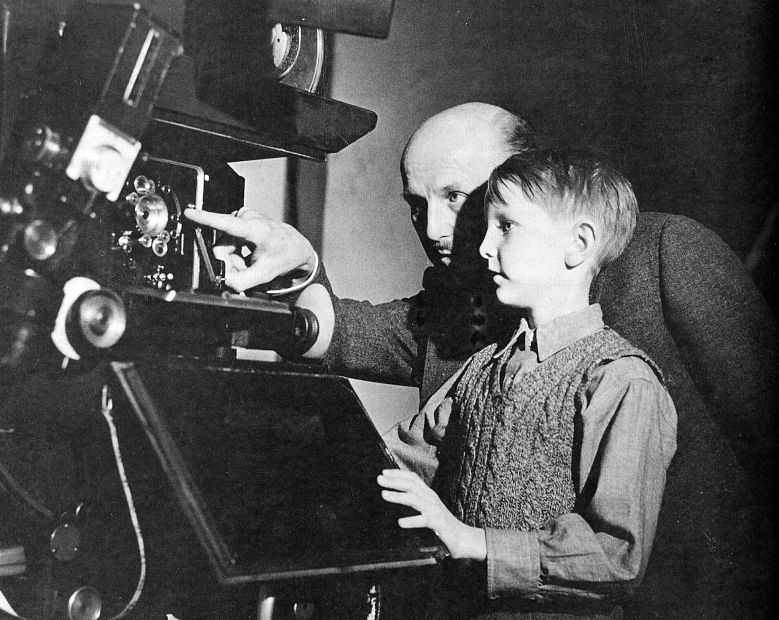

Mark’s father in Peeping Tom was a professor researching into the origins of fear and voyeurism: he tortures his son and films his reactions in silent black and white. We watch in horror as the father terrifies his child, his camera recording every flicker of fear. The traumatised child grows up to become the film’s shy, gentle, and quietly murderous photographer. (Pictured below: Michael Powell with his son Columba during the making of Peeping Tom) The father in those scenes with Columba was played by Powell himself, adding a further twist to a movie about a serial killer who films his victims. The subject alone so outraged the critics that they ignored the movie’s oblique, Freudian commentary on voyeurism in the cinema.

The father in those scenes with Columba was played by Powell himself, adding a further twist to a movie about a serial killer who films his victims. The subject alone so outraged the critics that they ignored the movie’s oblique, Freudian commentary on voyeurism in the cinema.

Powell maintains that he never really understood all the fuss. “To me it was a simple, good idea for a film," he says. “Leo Marks – who’d been a code-breaker during the war so naturally everything he did was double-edged – and I had been discussing doing a film about Freud, not a biography, but about him.

“And then John Huston announced he was making his film [Freud: The Secret Passion]. I never saw it, but it was a disastrous idea. But Peeping Tom really was a film about Freud, and we cast Carl Boehm, the Viennese actor. And it was such a model picture. We shot it in 30 days on a budget of £140,000 on schedule. And then when we’d finished we were all sitting there with our tails thumping on the floor, so pleased with ourselves.”

And the horrified critical reaction that followed? “I had no idea that critics were so innocent. I didn’t find the film shocking. But Anglo-American distributors should have taken space in the papers inviting people to come and decide for themselves, putting in all the things the critics said – ‘it’s lecherous, it’s terrible’. That’s been done before, but it works.

“Instead they just yanked the film straight out of the Plaza. I went down to see how it was doing, and found another film playing. They sold the television rights to some fly-by-night character in America who went bankrupt and died. And for 20 years the film practically vanished, and me with it. When I found it again, it was in a pretty bad state. Weird experience.” (Pictured below: Carl Boehm and Anna Massey in Peeping Tom)

This was not the first time a producer-distributor had pulled the plug on a Powell movie. In 1948, J Arthur Rank refused to give The Red Shoes a proper release because he couldn’t see its audience appeal.

This was not the first time a producer-distributor had pulled the plug on a Powell movie. In 1948, J Arthur Rank refused to give The Red Shoes a proper release because he couldn’t see its audience appeal.

The Archers, the nom d’ecran of Powell and Pressburger’s combined creative team, left Rank, with whom they’d had their big wartime successes, and went back to the producer who had first introduced them to each other, Alexander Korda. But with Korda came American co-productions, first with Samuel Goldwyn and then David O Selznick, which proved less than easy ventures.

In 1950 Powell and Pressburger made Gone to Earth for Selznick, who had admired A Matter of Life and Death (1946) and The Red Shoes (1948) and thought that an adaptation of Mary Webb’s novel would be a good vehicle for his wife, the actress Jennifer Jones.

Unfortunately the film lived up to its name, literally going to earth in America when Selznick didn’t like the Archers’ work and hired Rouben Mamoulian to reshoot some key scenes, eliminate the local colour, add a spoken prologue by Joseph Cotten, and then retitled his version of the film The Wild Heart. Gone to Earth in its original form would not re-emerge until the National Film Archive restored it.

Powell looks back ruefully on his experience with the Hollywood mogul: “Selznick was a strange man, a dangerous mixture. He always maintained that every David O Selznick movie had to be great, and usually they were only big, not great. He was really keen and boyish, and immensely powerful in the business. But somehow, except for Gone with the Wind, he never really made it. But we liked him.

“With Gone to Earth Selznick just wanted to say: ‘Those boys didn’t know what they were doing, I took hold of it and put it together, I don’t say that I actually directed the scenes with Jennifer Jones, but I masterminded them.’ And of course it was very difficult because at that time there was this tremendous passionate romance between Selznick and Jennifer Jones. We loved Jennifer, the whole crew did. She was a wonderful girl, simple, very straight. She could have been a great actress, she had all it takes, strength, imagination, and temperament. But she hadn’t a chance chained to Selznick’s wheel.” (Pictured below: Jennifer Jones in Gone to Earth)

Jones’s incandescent performance as the half-gypsy wild child Hazel, on the brink of womanhood and closer to her pet fox than her fellow humans, lights up the Hardyesque Technicolor melodrama. Hazel is pursued by two men, the timid ineffectual minister and the lecherous country squire, both of whom desire her without any true understanding of her nature. Gone to Earth also makes something mystical out of the Shropshire-Welsh border land and its wildlife.

Jones’s incandescent performance as the half-gypsy wild child Hazel, on the brink of womanhood and closer to her pet fox than her fellow humans, lights up the Hardyesque Technicolor melodrama. Hazel is pursued by two men, the timid ineffectual minister and the lecherous country squire, both of whom desire her without any true understanding of her nature. Gone to Earth also makes something mystical out of the Shropshire-Welsh border land and its wildlife.

There’s an echo of a different kind in Jones’s life. Hazel is literally hounded to her fate by her lover. In The Wild Heart you can spot Selznick’s scenes intercut with Powell’s if by no other clue than that Jones’ face is plumper and more heavily rouged: the fiery young actress once back in Hollywood is already giving way to the unhappy trapped star she became in the 1950s.

Powell tells the story of Jones and many of the other great actors he worked with in his first autobiography, A Life in Movies. The inspiration for the book came from his mother, a keen photographer. But he always found writing a chore, preferring to work with gifted screenwriters like his partner Emeric Pressburger, with whom he made 18 films, or Leo Marks, who wrote Peeping Tom.

“The cinema is a universal art, much more than books because it’s so effective and emotional," Powell says. "Everyone knows roughly what’s going on. Oh, it’s so wonderful... Once you’re in it, you never want to get out of it.”

Shunned for many years after Peeping Tom scandal, Powell hoped that working with Francis Ford Coppola at Zoetrope Studios in California in the early 1980s might have led to a return to directing. “It could have been wonderful but they were underfinanced and Coppola went a little bit wild. He put under contract two artists and wanted to use them in all the pictures at once, so they got in a muddle over the schedule.

"When I arrived they had been at it six months, and they were already in deep waters. I like Coppola but he’s not an executive and he was trying to be the head of the studio, make a picture and develop something new. He had the same bee in his bonnet as I had about trying to control the picture more, use process work more, and try to cut down on the expense. But he didn’t really know how to go about it, and he didn’t have the time. Pity. It was a great chance and he knows it. And he’s been working like a galley slave ever since to pay off all his debts, and made some strange pictures along the way.”

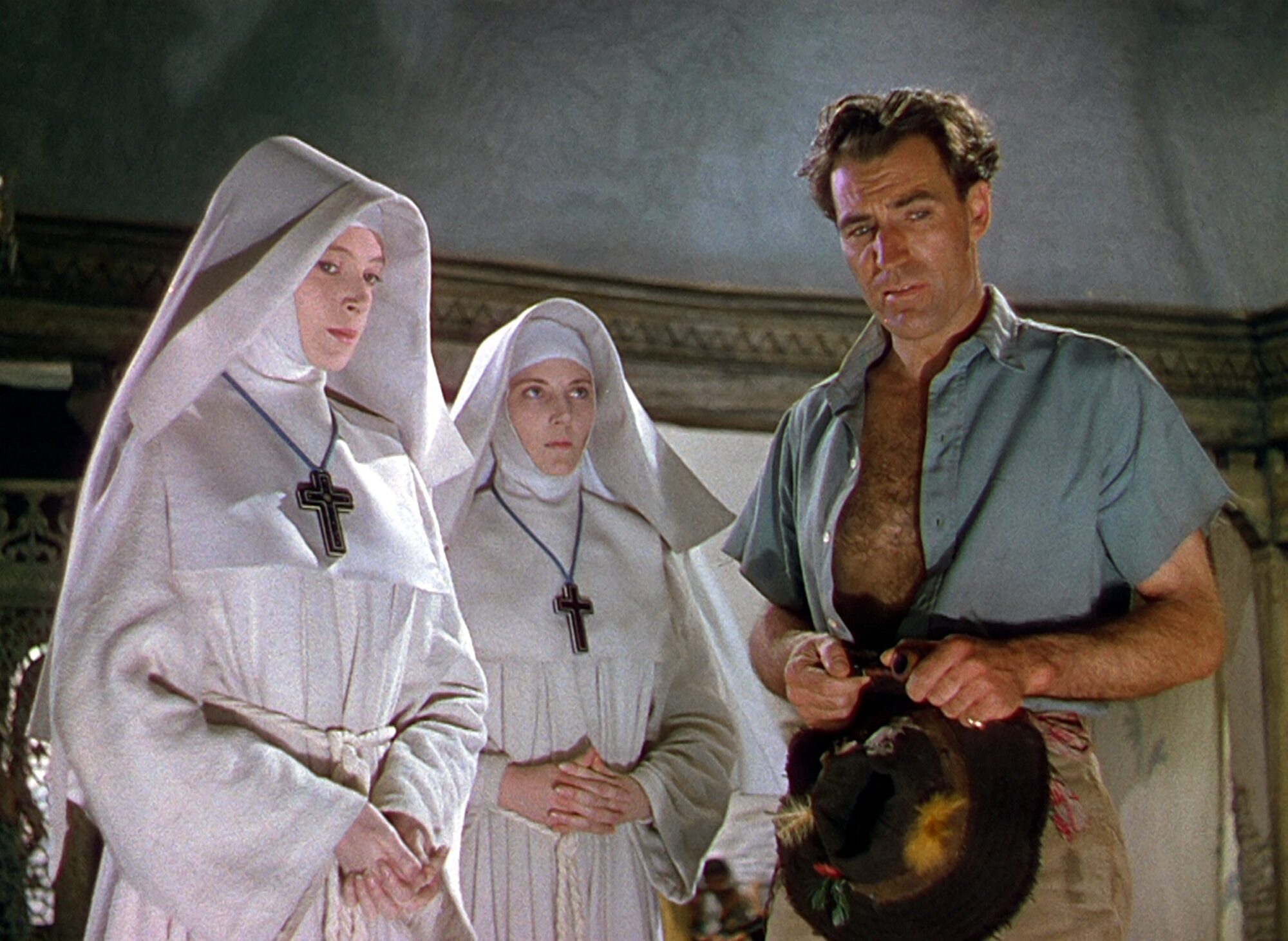

Coppola shares Powell's yearning for independence, not just from cost-cutting studio executives but also from the conventions of cinema. In A Life in Movies, Powell writes about his dream of a "composed cinema" in which "music, emotion and acting" made a complete whole, of which the music was the master. He feels he came closest to achieving that on Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948). (Pictured above: Deborah Kerr, Kathleen Byron, and David Farrar in Black Narcissus)

Coppola shares Powell's yearning for independence, not just from cost-cutting studio executives but also from the conventions of cinema. In A Life in Movies, Powell writes about his dream of a "composed cinema" in which "music, emotion and acting" made a complete whole, of which the music was the master. He feels he came closest to achieving that on Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948). (Pictured above: Deborah Kerr, Kathleen Byron, and David Farrar in Black Narcissus)

Starting his career in the silent era, Powell maintains that the coming of sound had repercussions that were far more acute than is commonly realised.

“The tragedy was that we were jogging along quite comfortably with all the best artists in Europe and having a lovely time,” he says. “But when talkies came in, it brought in vaudeville, ordinary actors, just everyone in an avalanche of talent. But all of it was commercial talent. They weren’t interested in mime or anything else but getting it on screen and making a buck.

“The cinema has never recovered from sound in my opinion. Only people who see silent films and analyse what they’re seeing or people with very long memories, who are probably out of a job like me, understand what we’ve missed.”

With sound the movies’ capacity to cross all national frontiers was severely curtailed, something that Powell, always strong on teamwork and with many foreign collaborators including the Hungarian Pressburger, feels passionately about. As a director he put together the best crews, even during the war when some of them were classified as "enemy aliens".

“When you get a group of artists together, everybody contributes something, that’s what really made our films interesting. We wouldn’t think of them as foreigners. In the film business there’s an incredible camaraderie; nobody’s foreign, they’re either good or bad at their job."

That camaraderie didn’t always sit well with the authorities. When Powell made The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, a film intended to encourage patriotic fervour in 1943, he not only famously irritated Churchill by making a hero out of an old duffer of an officer, but he also had Anton Walbrook play a German officer who is not a cartoon villain. (Pictured above: Roger Livesey in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp)

That camaraderie didn’t always sit well with the authorities. When Powell made The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, a film intended to encourage patriotic fervour in 1943, he not only famously irritated Churchill by making a hero out of an old duffer of an officer, but he also had Anton Walbrook play a German officer who is not a cartoon villain. (Pictured above: Roger Livesey in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp)

The suggestion that this was politically dangerous water to have sailed into during the war, provokes this reply: “I’m not very good at any ‘ism’, really. I’m just human. I have no axe to grind and no political theories of any kind. I simply liked the whole idea that they should be enemies, then friends, and that the old boy should go on still dreaming of this ideal friendship. It’s so very, very English.”

Add comment