Singular in its variousness, this is a three-act ballet that need some unpicking. No wonder those hooked on first acquaintance in 2021, like theartsdesk’s dance critic Jenny Gilbert, have been back to see it more than once.

So long as you accept that the interpretation by choreographer Wayne McGregor, composer Thomas Adès and artist Tacita Dean of hell, purgatory and heaven isn’t always contingent with Dante’s and Virgil's descent through the ever-narrowing circles of the damned, up the magic mountain of Purgatory to the garden where Beatrice awaits, and then on in a rare celestial flight, you’ll go with the surprising creative takes involved, at least in the first two parts.

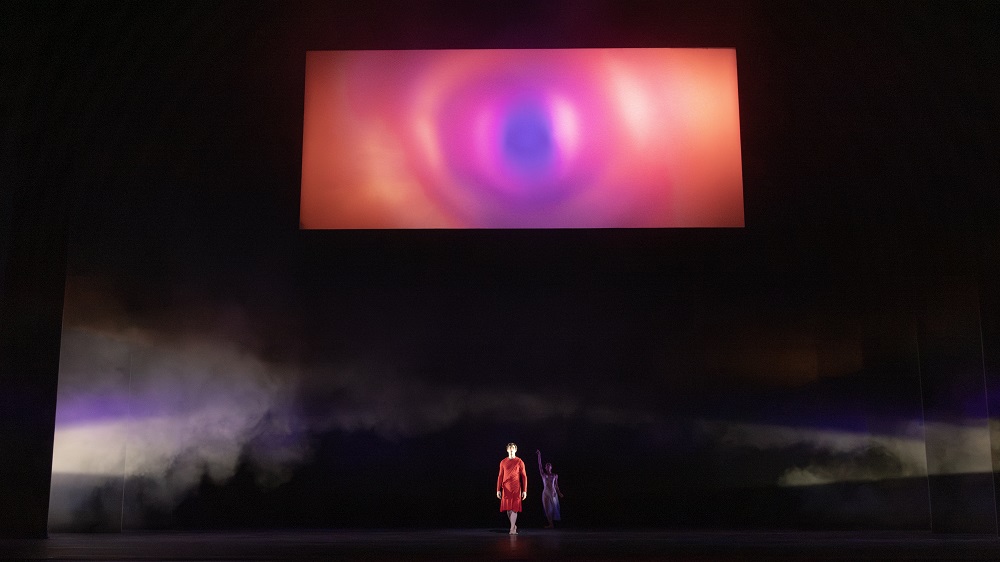

Adès himself tells us in the programme how, like many of us reading Dante for the first time, he was hooked on that topography. And yet no sense of down and up features until "Paradiso: Poemo Sacro," the weakest part of the triptych here in every sphere as it palpably is not in Dante. Not for him a wishy-washy heaven. And yet, accompanying the Cinemascope screen which shows us evolving planetary circles high above the dancers, not really meshing with them, Adès's music has a naively pretty "hook" to last most of the journey, but doesn't move forward through space, a quality SImon Rattle identified in John Adams's music (and what a marriage of true souls that might have been).  Adding a choir at the end doesn't really budge the score from its prettily-orchestrated essential state, multiple modulations notwithstanding. Two composers have captured this "inexpressive lightness" and the direction of travel - Elgar in Part Two of The Dream of Gerontius and Mahler in his Eighth-Symphony setting of Goethe's final scene to Faust Part 2, where the poet acknowledged his debt to Dante's Paradiso.

Adding a choir at the end doesn't really budge the score from its prettily-orchestrated essential state, multiple modulations notwithstanding. Two composers have captured this "inexpressive lightness" and the direction of travel - Elgar in Part Two of The Dream of Gerontius and Mahler in his Eighth-Symphony setting of Goethe's final scene to Faust Part 2, where the poet acknowledged his debt to Dante's Paradiso.

This is the one sequence where long-term musical movement was an option. "Purgatorio: Love", where McGregor eschews all the figures on the ascent of the purgatorial mountain in favour of a backstory to Beatrice, whom Dante encounters right at the top, is a more tightly-knight dance suite than the hell's-cabaret "Inferno: Pilgrim". The orchestra's response to the recorded ancient prayer (baqashot) in a Syrian synagogue - this could just as easily be an Islamic muezzin - gives us the "real" Adès, if he's anywhere to be found, in wind and brass writing. that veers between the punchy and the lyrical. It's the most original music in the score, and compels until the crucial afterlife meeting in the garden. We surely need something of the beauty and pathos in Dante's poetry here, but we get a bright banality which explodes the magic of the previous middle-eastern homages. It also works against the miracle orf Lucy Carter's lighting on Dean's over-coloured photograph of a jacaranda tree in a Los Angeles street, evolving into lovely lilac light.

The various illumiinated transformations of Dean's Doré-esque chalk on blackboard for "Inferno" may give it dimension, but can't counter the relative flatness of a hell that doesn't essentially evolve downwards. The musical choice has to be taken here on its own terms: a divertissement with Lisztian quotations and transformations, superbly scored to veer between heavy darkness and flickering light. But as Jenny Gilbert pointed out in her original review, a first-time viewing will tell us little of McGregor's choices from the savage parade of the damned, for the simple reason that Dante's characters real and mythical give us their contexts, and dance can't (least of all when they all sport the same chalked black costumes). Francesca and Paolo could be any tormented lovers, Dido any suicide who kills herself following the desertion of her love. When have we reached the souls near the bottom in the frozen lake? Is that Beatrice making an early appearance before Dante sees the light? No; it turns out to be Satan. The dissonant chords might tell you so, but they come too abruptly on the heels of a joky ensemble number, which sounds more like Shostakovich in revue mode than Liszt. The overall achievement is hard to rate, but in terms of Adès's work for the theatre, I'd place it somewhere between the too establishment-friendly The Tempest and the more arresting instrumental sounds, though not the angular vocal writing for the women, of The Exterminating Angel. As so often with this composer, the head is engaged, the ears especially, but the heart less so.

The overall achievement is hard to rate, but in terms of Adès's work for the theatre, I'd place it somewhere between the too establishment-friendly The Tempest and the more arresting instrumental sounds, though not the angular vocal writing for the women, of The Exterminating Angel. As so often with this composer, the head is engaged, the ears especially, but the heart less so.

It's not my place to discuss the quality of the dancing, but William Bracewell's Dante (pictured above in "Inferno") carries the emotional weight well, Francesca Hayward and Fumi Kaneko share graceful honours as Beatrice, Anna Rose O'Sullivan commands the stage as Dido and Leo Dixon undulates creepily as the damned Pope. Last time round, conducting honours were shared between Adès and Koen Kessels; this time it's Jonathan Lo of the Australian Ballet. He's surely authoritative. And the orchestra must be grateful to play a score very much more rewarding than, say, the one for Don Quixote.

Add comment