Street Scene, Young Vic Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Street Scene, Young Vic Theatre

Street Scene, Young Vic Theatre

Kurt Weill's American opera seethes with stifled passions and broken dreams

“A simple story of everyday life in a big city, a story of love and passion and greed and death.” That was how Kurt Weill described Elmer Rice’s 1929 play, Street Scene, set on the front stoop of a New York brownstone in sweltering summertime.

This revival by John Fulljames for the Opera Group and the Young Vic was first seen in 2008; returning now, it has a roughness that, while it might displease operatic purists, doesn’t detract from either its defiant Big Apple swagger or its intense, brooding quality of routine deprivation and stifled dreams.

The band – for the first part of the run the BBC Concert Orchestra under musical director Keith Lockhart, later the Southbank Sinfonia Touring – are positioned within designer Dick Bird's graffiti-scarred block, festooned with lines of washing, its iron staircases rising from stained sidewalks that bisect the auditorium. Here the neighbours gather, wilting in the heat, the women vainly attempting to fan a little cool air up their sweat-sodden skirts, to share confidences or grievances, or gloat over some tasty tidbit of gossip, the nasty nourishment of lives starved of many moments of joy or pleasure.

They are a richly multicultural crowd, yet disparaging remarks about “foreigners”, “Squareheads” and “Polacks” drop casually from the sour-faced Queen Bitch of the backbiting circle, Emma Jones (an acid Charlotte Page). But the object of bilious tittle tattle is most often Anna Maurrant (Elena Ferrari), wife to violent stage-hand Frank (Geof Dolton) and mother to young tearaway Willy and his wistful sister, Rose (Susanna Hurrell). Yearning for tenderness and some respite from her existence of cowed drudgery, Anna is having an affair with the milkman, Steve Sankey (Paul Featherstone) – and almost everybody knows it. It’s only a matter of time until the dangerously volatile Frank does, too.

Meanwhile, other domestic climaxes and crises play out: a family is evicted, a young couple have their first child, and romance blossoms, with the quiet optimism of weeds growing through cracked flagstones, between Rose and Sam Kaplan, the earnest, bookish son of an elderly Jewish radical who is regarded with mistrust by the building’s other inhabitants. And children scamper everywhere, marking out this little patch of tatty turf as their own with doodles, names and slogans scrawled in white chalk. Weill’s score is as restless and lively as they are, almost cinematic in its scale.

Meanwhile, other domestic climaxes and crises play out: a family is evicted, a young couple have their first child, and romance blossoms, with the quiet optimism of weeds growing through cracked flagstones, between Rose and Sam Kaplan, the earnest, bookish son of an elderly Jewish radical who is regarded with mistrust by the building’s other inhabitants. And children scamper everywhere, marking out this little patch of tatty turf as their own with doodles, names and slogans scrawled in white chalk. Weill’s score is as restless and lively as they are, almost cinematic in its scale.

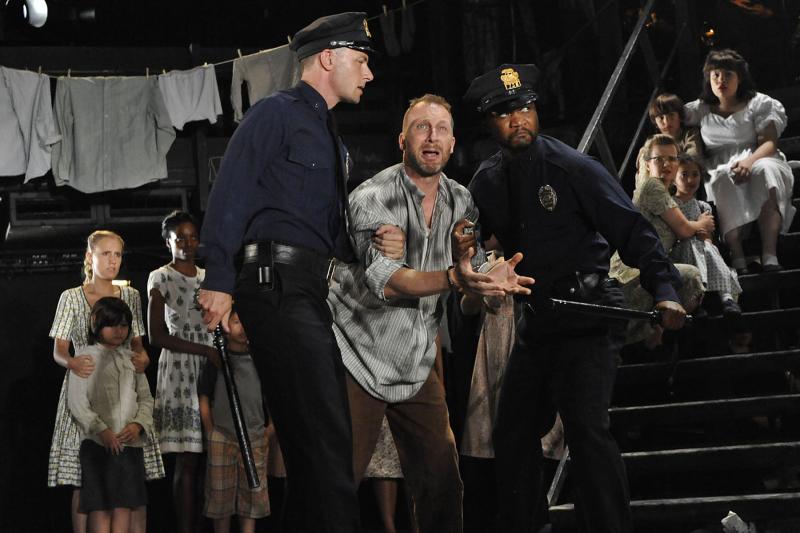

One moment there’s a rolling blues refrain sung by the building’s soft-spoken black janitor; next, an ecstatic ode to ice cream for flamboyant Italian resident Lippo Fiorentino (Joseph Shovelton), to which, in Arthur Pita’s vibrant choreography, the cast lift their vanilla cones aloft like so many Statues of Liberty. Another stand-out sequence is supplied by the bravura song and dance sequence between Mrs Jones’ brassy daughter Mae and her boozy beau (Kate Nelson and John Moabi, pictured, above right), an explosion of shameless, high-kicking, hot-blooded sensuality lighting up a down-at-heel street.

Most memorable of all, though, are the moments when Hughes’ heartbreaking poetry comes to the fore. Anna Maurrant’s huge aria Somehow I Never Could Believe, which tells the story of a marriage begun in naiive hope, now mired in misery, is exquisitely desolate. “I don’t know,” she sings despairingly. “It looks like something awful happens/In the kitchens where women wash their dishes... the greasy soapsuds drown our wishes.” Ferrari delivers it with devastating simplicity. And Dolton’s Frank, confronting his ruined, wasted years and the awful consequences of his own violent temper, summons a fierce and tragic emotional intensity.

The acoustics are uneven and not every step, line and note executed by the cast, which includes young community performers, is altogether in place. But this is a pungent, gutsy work of music theatre, pulsating to the relentless rhythm of irrepressible urban life.

rating

Buy

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Comments

The reviewer really is too

How harsh you are, first

How harsh you are, first messager. In response - since I went back to see this fine show last night after the run a couple of years back - Street Scene is minorly, not majorly, flawed. Some of the lyrics are toe-curling, some of the numbers superfluous, but there are patches of Weill at his absolute genius best (the underscoring for the dialogue has extraordinary invention and detail). The hybrid nature was a strength, not a weakness, on Broadway, and to my mind remains so. I don't find anything banal about the resolution: desolate daughter strikes out on her own, rejects implausible soft options. Both Maurrant women, mother and daughter, were superbly portrayed last night - all you need are a strong technique and empathy with the characters (not difficult to find). You're stretching a point on the multi-racial issue when we willingly suspend our disbelief in other areas of the theatre where the performances are good enough.

As for the circumstances, don't blame the supposed 'cavern' for the sound problem, but the fact that the orchestra is playing directly out at the audience. I'd rather hear a fullish complement for Weill's masterly orchestrations and voices courageously unmiked, rather than the where's-the-voice-coming-from amplification I've heard unnecessarily engaged in the Menier. The seats seemed perfectly comfortable to me, space fine (this from a long-legged person), sightlines good everywhere I looked. You miss the point about the novel programme - it's supposed to be a broadsheet of the times. £4 would have been overpriced, but £2.50 is just fine. And the 'pub' aspect in no way impinges on your experience in the auditorium. Bah humbug!