Venice Biennale 2022 review - The Milk of Dreams Part 1: The Giardini | reviews, news & interviews

Venice Biennale 2022 review - The Milk of Dreams Part 1: The Giardini

Venice Biennale 2022 review - The Milk of Dreams Part 1: The Giardini

The biggest and most challenging exhibition you’ll be seeing in some time

Cecelia Alemani's vision for The Milk of Dreams, the International Exhibition at the Venice Biennale 2022 had me excited – and perplexed – from the moment I heard about it.

Never mind the national pavilions which tend to dominate coverage of the world’s biggest and oldest art festival, the International Exhibition is the central event at any Venice Biennale: the chance for a single curator to stamp their vision on the culture of their time in a truly epic exhibition traversing two colossal venues. The Milk of Dreams features works by 213 artists from 58 countries spread through the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, the Biennale’s lagoon-side site, and the neighbouring Arsenale shipyard. The latter space alone is nearly half a mile in length. Yet 2022’s theme and rationale seemed simultaneously too fanciful in conception and too overweening in range - even for a show on this scale - when they were announced in February by Alemani, director of New York’s High Line art programme, and the first Italian woman to curate this exhibition.

The Milk of Dreams takes its title from a 1950s children’s book by Surrealist painter Leonora Carrington, set in a “magical world where life is constantly re-envisioned through the prism of the imagination… where everyone can change, be transformed, become something or someone else.” The show, is conceived as an imaginary journey, in which Carrington’s “otherworldly creatures, along with other figures of transformation, (act) as companions on an imaginary journey through the metamorphoses of bodies and definitions of the human.”

Alemani and her co-curators are promoting instead a softer, more poetic and inclusive Surrealism, that’s been side-lined until very recently, not just because of the misogyny that was intrinsic to mainstream Surrealism

Along the way the show will ask, we are told, “How is the definition of the human changing? What are our responsibilities towards the planet, other people, and other life forms? And what would life look like without us?” Good grief, is that all?

You can hardly accuse Alemani of failing to think big. And better fanciful, than clumpingly predictable. But does her project represent a courageous assertion of the power of the imagination in the aftermath of a devastating global pandemic? Or is it more a retreat into whimsical wishful thinking in the face of endemic intolerance and catastrophic climate change. The current vogue for personal transformation seems largely confined to the privileged West. And while Alemani talks about “responsibilities towards the planet”, her rarefied tone, and starting point in magical worlds and imaginary journeys, suggests the show won’t be digging too deeply into the dirty actualities. And this was before the nastiest war of recent times had even started.

But hell, you can’t criticise what you haven’t seen. And there was more than enough in the sheer kooky, saccharine-tinged hubris of the enterprise to get me flying half way across Europe (my first time on a plane in three years) to see what it was going to look like.

And while I was still at baggage claim at Marco Polo Airport, Alemani seemed to have added a few sub-clauses to the proposition behind The Milk of Dreams, wanting now to examine the “interrelations of species” and to “imagine a posthuman condition that challenges the modern Western vision of the human being – and especially the presumed universal ideal of the white, male Man of Reason.” Oh and yes, the large majority of the artists will be women.

Without getting bogged down in nit-picking before we’re even through the doors of the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, isn’t there a laziness in that reference to whiteness and maleness? The Renaissance-Enlightenment rationalist tradition may have enabled the Slave Trade and planet-destroying chemicals, and most of its best known exemplars were undoubtedly white men. But aren’t many of today’s inheritors of that “presumed universal ideal” actually black women, in the form of scientists, doctors and, not least, artists?

But let’s put that aside as we confront the show’s gobsmacking opening exhibit: German artist Katharina Fritsch’s "Elephant": a life-cast of an enormous elephant in deep green polyester, that looms up into the frescoed cupola of the Central Pavilion’s entrance hall, reflected in four gigantic mirrors (main picture). It embodies the notion of the “interrelations of species” in an implicit and visually awe-inspiring critique of the way old school “heroic” museums – such as the Natural History Museum – frame our proprietorial attitudes towards the natural world. And after that big, punchy opening we’re shown the first examples of the promised “metamorphoses of bodies”: envisionings of the “hybrid, manifold beings” that Alemani imagines will be replacing the Man of Reason in an already existent reality where “boundaries between bodies and objects have been utterly transformed” by technology.

And after that big, punchy opening we’re shown the first examples of the promised “metamorphoses of bodies”: envisionings of the “hybrid, manifold beings” that Alemani imagines will be replacing the Man of Reason in an already existent reality where “boundaries between bodies and objects have been utterly transformed” by technology.

Judging by Romanian artist Adra Ursata’s extraordinary glass sculptures, cast from digitally-scanned bodyparts and everyday objects, the human of the futures – if we are still “humans” by then – will be a monstrous hybrid of a plastic water bottle, a heap of bondage-wear and a machine gun (Adra Ursata’s "Lead Crystal Sculpture", pictured above). The late Mrinalini Mukherjee’s enormous draped sculptures in woven hemp hint at primordial presences – Hindu deities perhaps – and the “bumps and folds of human sexual organs”, the wall texts tell us.

For all the show’s futuristic rhetoric, much of the work in this early section has a comfortingly old fashioned flavour. Ethiopian painter Merikokeb Berhanu’s rich colours and biomorphic shapes bring to mind the neo-traditional forms of Africa’s post-Independence era, rather than the more conceptual approach that prevails across the continent today. Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuna’s room-filling installation of suspended driftwood and other ephemera may critique “the sins of sexism and colonialism”, but the accompanying paintings feel like cutesy updated magic realism.

But it’s with a display on neglected women Surrealist artists, under the title "The Witch’s Cradle", that the exhibition really sets out its stall. Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo’s hallucinatory dream paintings hang alongside Leonor Fini’s poetic reversals of the male gaze and Claude Cahun’s androgynous photographic self-portraits. Belgian artist Jane Graverol merges painting and photography in her sphinx-like "L’Ecole de la Vanitas", which dates from 1967, but feels, significantly, much older in spirit. (Pictured below, Remedios Varo's "Simpatia La Rabia Del Gato", 1955)

If the two erstwhile best known works by women Surrealists aren’t included – Meret Oppenheim’s "Object" (a fur-covered cup and saucer) and Lee Miller’s "Radical Mastectomy" (a severed breast on a plate) – that’s probably because they feel too much like pieces of hard-and-nasty, bad boy Surrealism that just happen to be by women.

If the two erstwhile best known works by women Surrealists aren’t included – Meret Oppenheim’s "Object" (a fur-covered cup and saucer) and Lee Miller’s "Radical Mastectomy" (a severed breast on a plate) – that’s probably because they feel too much like pieces of hard-and-nasty, bad boy Surrealism that just happen to be by women.

Alemani and her co-curators are promoting instead a softer, more poetic and inclusive Surrealism, that’s been side-lined until very recently, not just because of the misogyny that was, we are now persuaded, intrinsic to mainstream Surrealism, but because it didn’t conform to the formalist – for which, read male-oriented – orthodoxies of Modernist art criticism. Beside the punchy shock-jockery of Dali, Magritte, Ernst and co, the works of Varo and Carrington have tended to be written off as twee and illustrative (and frankly I can quite see why). Yet with the overturning of categories that’s come to a head with #MeToo and Black Lives Matter those positions of esteem appear to be going into reverse.

It’s still bemusing, though, to find an entire room devoted to Paula Rego. Skillful and extraordinarily popular her sinister nursery symbolism may be, but I’ve always found it not just crushingly literal, but fundamentally conservative – backward, not forward looking. I’d as soon have expected to have encountered Lucian Freud here as a pointer to the future – if, of course, he’d been a woman.

It’s only, in fact, with an appearance by the male Martinican poet Aime Cesaire in a section on multi-cultural precursors and outsider artists – and then only admitted in partnership with his wife Suzanne – that it occurs to me that everything I’ve seen so far is by women. But then when you’re looking at the work of only one demographic, it’s the variety rather than the commonality you notice. The show is already so multifarious, you hardly register the further difference of gender – or lack of. And with most of the big collateral exhibitions around the Biennale given over to old school, alpha male “hero” artists – Kiefer, Kapoor, Baselitz, Gormley and on and on – you hardly miss that vibe here.

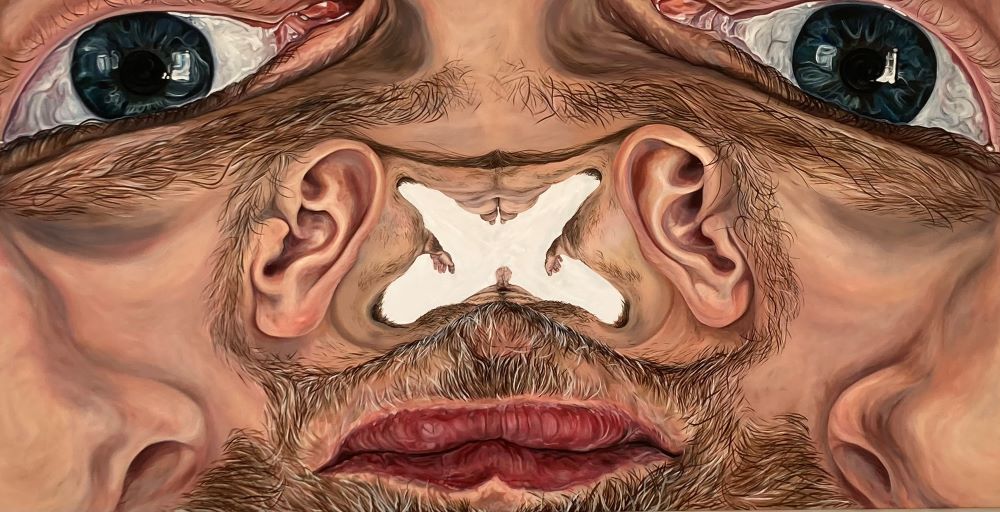

If The Milk of Dreams seems to be looking to the past for the makings of a new and more expansive, oestrogen-powered Surrealism, much of the rest of the first part of the show seems a demonstration of the fact that it’s already here, with endless permutations on the human body as “hybrid, manifold being”.  German artist Jana Euler’s lumpen photo-realist paintings turn the body outside-in, offering brain-twisting vistas through the interior and exterior of the human form (Jana Euler's "Venice Void 2022", pictured above). American artist Christina Quarles tears the body into strips of brilliantly coloured painterly matter in canvases that resemble a kind of brutalised updated feminist pop part. Proxies for the human body are everywhere, many of them decidedly sinister, from Danish artist Sidsel Meineche Hansen’s repurposed sex dolls to Polish artist Aneta Grzeszykowska’s disturbingly life-like sculptures of herself, posed in photographs with her daughter as a kind of lifeless stand-in mother.

German artist Jana Euler’s lumpen photo-realist paintings turn the body outside-in, offering brain-twisting vistas through the interior and exterior of the human form (Jana Euler's "Venice Void 2022", pictured above). American artist Christina Quarles tears the body into strips of brilliantly coloured painterly matter in canvases that resemble a kind of brutalised updated feminist pop part. Proxies for the human body are everywhere, many of them decidedly sinister, from Danish artist Sidsel Meineche Hansen’s repurposed sex dolls to Polish artist Aneta Grzeszykowska’s disturbingly life-like sculptures of herself, posed in photographs with her daughter as a kind of lifeless stand-in mother.

Canadian artist Elaine Cameron-Weir reduces the body to a set of aluminium crates, which are, we are told, “US military transfer cases” – coffins for transporting soldiers killed in action back to their relatives. Cameron-Weir’s work alludes variously, to “laboratory equipment, torture devices, instruments of fetishism, military gear or medieval armour”, holding “associations of protection, pleasure and pain in a precarious balance”. So much for the widely disseminated belief – and not least by women themselves – that women’s art is by its very nature nurturing and emotionally supportive.

And so far, so coherent as an exhibition; though the artist who covers most of its key bases is Ovartaci, a transsexual Danish outsider Surrealist who spent much their life creating human proxies: life-size metal cut-outs of women – seen here hanging, a shade disturbingly, from a clothes rack – that were intended as “companions” for outings that never took place. As the artist died in a psychiatric hospital in 1985, they’re unlikely to be providing further pointers for the future of art – or none that we can envisage yet.

And so to the second leg of the show at the Arsenale, where the whole shebang proceeds to rapidly unravel.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment