Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland on a lifetime of chronicling the dramatic changes in the Arctic | reviews, news & interviews

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland on a lifetime of chronicling the dramatic changes in the Arctic

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland on a lifetime of chronicling the dramatic changes in the Arctic

For him, the most ominous change has been the appearance of dark patches on the Greenland ice sheet

Sebastian Copeland’s images of the Arctic may look otherworldly – with their tilting cathedrals of ice, hypnotic light, and fractured seascapes that seem to stretch to infinity – but it would be a mistake to see them that way.

For Copeland’s whole mission is to make us see how intimately our lives are caught up with a region which – for all its frozen austerity – is in flux. In his most recent book of photographs, The Arctic: A Darker Shade of White (winner of an International Photography Award), he writes that Arctic sea ice has just lost “more volume in 30 years than it has in the last 5,000”. Whether you’re hurtling through northern Greenland on a dog sled or attending – as he is when we talk – a photography festival near Dubai, you will, without doubt, feel the impact as weather becomes ever more schizophrenic and sea levels surge.

One of the challenges of getting this message across is the fact that to the untutored eye, the primary impact of the photographs is the magnificence of what they depict. Maybe you’ll be beguiled by the geometrically pristine reflections of icebergs off Ellesmere Island in Canada, or by the titanic needle of ice in northern Greenland besieged by ominous clouds. Yet for Copeland – whose exhibition The Vanishing North (based on his book) is currently at the Xposure 2025 Festival at Sharjah – the changes he has observed over the last two decades have left him in no doubt of the urgency of his message. The most ominous sign, for him, has been the appearance of dark surfaces over the south Greenland ice sheet, “the result of dust and carbon particles transported by the jet stream,” he writes. “The dark shade reverses the ice’s ability to reflect solar energy back into the atmosphere…[contributing] directly to the accelerated melting of the Greenland ice.”

“We see ice as an inanimate element, but that couldn’t be further from the truth,” he says when we talk on Zoom. “The incidence of the ice on the planet has been so instrumental in the development of life. Without ice 650 million years ago, we wouldn't have seen an explosion of multicellular life forms [scientific theories about “Snowball Earth” suggest that limited photosynthesis in frozen-over oceans led to fewer nutrients which meant that only larger organisms survived]. Today ice, especially at the poles, regulates our climate – and as it disappears it’s having an impact on Earth’s entire biodiversity chain.”

“We see ice as an inanimate element, but that couldn’t be further from the truth,” he says when we talk on Zoom. “The incidence of the ice on the planet has been so instrumental in the development of life. Without ice 650 million years ago, we wouldn't have seen an explosion of multicellular life forms [scientific theories about “Snowball Earth” suggest that limited photosynthesis in frozen-over oceans led to fewer nutrients which meant that only larger organisms survived]. Today ice, especially at the poles, regulates our climate – and as it disappears it’s having an impact on Earth’s entire biodiversity chain.”

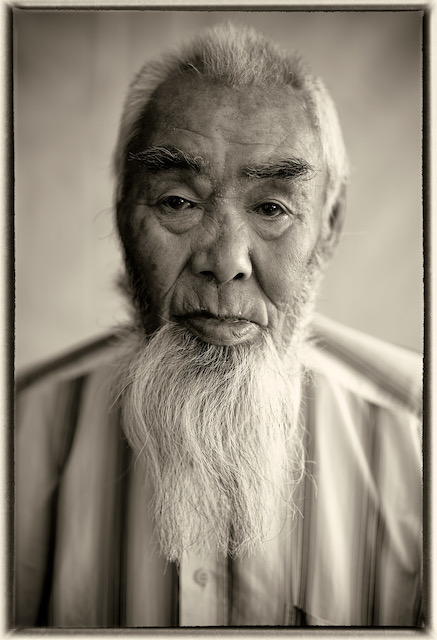

Some of Copeland’s images are portraits of the Inughuit [sic] people in Greenland, who have been among the populations most directly impacted by the receding sea ice. He has come to know many of them well over his decades of travelling in the Arctic. One photograph shows a hunter dressed fearsomely in polar bear, seal, caribou and wolf hides. Another shows a man with a striking white goatee (pictured above – also a hunter) whose family was forcefully relocated in the 1950s from what became the US Thule military airport base and is now the Pituffik Space Base. At a point when Trump’s proprietary posturing has pushed Greenland into the headlines, what has Copeland found from his more nuanced relationship with the country?

He talks about the second hunter with a goatee – Akku Suersaq – who was born in 1939 and was 82 when Copeland did his portrait just a few months before he died. “His generation was so close to the land and the hunting tradition. He used to sleep in igloos during the winter. Yet he was forced to go from the Ice Age to the Space Age in such a short time. He ended up in a retirement facility in Qaanaaq, surrounded by people with iPhones. I wanted to create a record of this unique culture in the northern latitudes, where people from a very traditional culture are being forced to cope with a rapidly transforming world.”

It's just one example of how the balance of life in these remote communities was being jolted even before Trump’s intervention. Talking more specifically about what he describes as Trump’s “pipe dream” Copeland declares, “Several people I’ve been talking to are saying ‘we’ve been under administrative control from Denmark for more than 300 years. What might it mean to have that kind of a relationship with a more powerful country that will enable us to have access to more capital?’” Recent reports have shown that Greenlanders are certainly interested in renegotiating their governmental contract; while one opinion poll showed that 85% don’t want to belong to the US, the idea of independence combined with free association with countries including Canada and Norway is of interest. Whatever the outcome, Copeland thinks the combination of rapid geopolitical and climatic change means “this is an existential moment in the history of Greenland”. While there’s no shortage of conceptual challenges negotiating the Arctic (and Antarctic, where he has also made films and put together images for books), the physical challenges are also substantial. Most people who are aware of Copeland’s work know about his prowess as an explorer – in 2017, the American magazine Men’s Journal named him as one of the 25 most adventurous men of the last 25 years. His trips to the Arctic include making a documentary, Into the Cold: A Journey of the Soul, about his arduous 2009 expedition with Keith Heger to the geographical North Pole that won best director award at the Los Angeles Reel Film Festival. He also (together with Eric McNair-Landry) in 2010 went kite skiing across the 2300 km length of the Greenland ice sheet, in the process setting a world record for the longest distance travelled on kites and skis over a 20-hour period.

While there’s no shortage of conceptual challenges negotiating the Arctic (and Antarctic, where he has also made films and put together images for books), the physical challenges are also substantial. Most people who are aware of Copeland’s work know about his prowess as an explorer – in 2017, the American magazine Men’s Journal named him as one of the 25 most adventurous men of the last 25 years. His trips to the Arctic include making a documentary, Into the Cold: A Journey of the Soul, about his arduous 2009 expedition with Keith Heger to the geographical North Pole that won best director award at the Los Angeles Reel Film Festival. He also (together with Eric McNair-Landry) in 2010 went kite skiing across the 2300 km length of the Greenland ice sheet, in the process setting a world record for the longest distance travelled on kites and skis over a 20-hour period.

At the age of 60, Copeland is still clearly hungry – both for adventure and for finding new ways of drawing people's attention to what's happening in the Arctic and the Antarctic through his photography. Talking about his latest book, Graeme Chesters, Research Director of 90 North Foundation, an organisation that campaigns to protect the biodiversity of the Central Arctic Ocean, praises the way that Copeland "combines personal testimony, revealing scientific insight and dramatic imagery to convey the urgency and importance of conserving and preserving the Arctic environment”. Though it’s not just the dramatic icescapes, it’s also the more intimate images that strike the message home about what’s at stake. Take the calligraphy-style perfection of his solitary Arctic tern perfectly reflected in the still Arctic water, or the quietly devastating close-up of a decaying polar bear.

Figures who have written forewords to Copeland’s books in the past include the late President Gorbachev and Leonardo di Caprio. For The Arctic: A Darker Shade of White, the English zoologist and primatologist Jane Goodall has drawn on her extensive experience in Africa to point out the connection between what happens in the Arctic and everywhere else in the world. “The loss of ice is not just a danger to those who live there,” she writes. “It also impacts weather patterns that affect all parts of the globe, manifesting in the worsening of storms, floods, droughts, heat waves and wildfires. Initially this disproportionately affected the poorer nations, but today the wealthy nations are also feeling the effects.”

In other words, no one is immune. As Copeland says, “If I’ve learnt one thing from my work, it’s about the interconnectedness of all systems. If, for example, spring comes early in the Arctic, then the breeding cycle peaks earlier than it used to, and when this doesn’t match food supply it impacts on the survivability of chicks. This doesn’t just have an effect on the local ecosystem, it affects wherever the birds fly back to. So it can easily create a domino effect; we see biodiversity affected, which can, for instance, lead to a proliferation of insects impacting on local agriculture, which in turn can reduce food production and lead to the migration of people. Right there you see how the health of the Arctic impacts on the health of this entire planet.”

In other words, no one is immune. As Copeland says, “If I’ve learnt one thing from my work, it’s about the interconnectedness of all systems. If, for example, spring comes early in the Arctic, then the breeding cycle peaks earlier than it used to, and when this doesn’t match food supply it impacts on the survivability of chicks. This doesn’t just have an effect on the local ecosystem, it affects wherever the birds fly back to. So it can easily create a domino effect; we see biodiversity affected, which can, for instance, lead to a proliferation of insects impacting on local agriculture, which in turn can reduce food production and lead to the migration of people. Right there you see how the health of the Arctic impacts on the health of this entire planet.”

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland on a lifetime of chronicling the dramatic changes in the Arctic

For him, the most ominous change has been the appearance of dark patches on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland on a lifetime of chronicling the dramatic changes in the Arctic

For him, the most ominous change has been the appearance of dark patches on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Lygia Clark: The I and the You, Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, Whitechapel Gallery review - breaking boundaries

Two artists, 50 years apart, invite audience participation

Lygia Clark: The I and the You, Sonia Boyce: An Awkward Relation, Whitechapel Gallery review - breaking boundaries

Two artists, 50 years apart, invite audience participation

Mike Kelley: Ghost and Spirit, Tate Modern review - adolescent angst indefinitely extended

The artist who refused to grow up

Mike Kelley: Ghost and Spirit, Tate Modern review - adolescent angst indefinitely extended

The artist who refused to grow up

Monet and London, Courtauld Gallery review - utterly sublime smog

Never has pollution looked so compellingly beautiful

Monet and London, Courtauld Gallery review - utterly sublime smog

Never has pollution looked so compellingly beautiful

Michael Craig-Martin, Royal Academy review - from clever conceptual art to digital decor

A career in art that starts high and ends low

Michael Craig-Martin, Royal Academy review - from clever conceptual art to digital decor

A career in art that starts high and ends low

Add comment