In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine 1900-1930s, Royal Academy review - famous avant-garde Russian artists who weren't Russian after all | reviews, news & interviews

In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine 1900-1930s, Royal Academy review - famous avant-garde Russian artists who weren't Russian after all

In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine 1900-1930s, Royal Academy review - famous avant-garde Russian artists who weren't Russian after all

A glimpse of important Ukrainian artists

Ukraine’s history is complex and often bitter. The territory has been endlessly fought over, divided, annexed and occupied. From 1917-20 it enjoyed a brief period of independence before being swallowed up once more by the Soviet Union after a vicious three year war – an example that Vladimir Putin is copying with his monstrous invasion.

Now Ukrainians are being forced to fight, once more, for independence is an appropriate time to reveal that many artists of the so-called Russian avant-garde were actually from Ukraine. Famous pioneers of abstract art such as Kasimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin, Alexandra Exter, Sonia Delaunay and Davyd Burliuk were born or raised there.

And as Russian bombs rain down, for safety it makes sense to send one’s art treasures abroad. So most of the exhibits on show at the Royal Academy are from Ukraine’s National Art Museum and Museum of Theatre, Music and Cinema, which means that the exhibition’s remit is limited by what they own.

Exter was a powerhouse of creativity as a painter and theatre designer (pictured right: Composition (Genova), 1912). Born in what is now Poland, she grew up in Kyiv where she studied art before moving to Paris in 1907. She met Picasso and Braque, exhibited there and became a key player in the art scene. Over the next few years she jet-setted between Paris, Rome, Moscow, Saint Petersburg and Kyiv. She was especially interested in Ukrainian folk art and in 1915 set up craft co-ops in the villages of Skoptsi and Verbivka. In 1918 she set up a private art school in Kyiv teaching painting and theatre design which produced the generation that created Kyiv’s radical theatre scene.

Exter was a powerhouse of creativity as a painter and theatre designer (pictured right: Composition (Genova), 1912). Born in what is now Poland, she grew up in Kyiv where she studied art before moving to Paris in 1907. She met Picasso and Braque, exhibited there and became a key player in the art scene. Over the next few years she jet-setted between Paris, Rome, Moscow, Saint Petersburg and Kyiv. She was especially interested in Ukrainian folk art and in 1915 set up craft co-ops in the villages of Skoptsi and Verbivka. In 1918 she set up a private art school in Kyiv teaching painting and theatre design which produced the generation that created Kyiv’s radical theatre scene.

On show are three of her early cubo-futurist paintings plus costume and set designs by herself and students such as Anatol Petrytskyi, who was a painter and brilliant theatre designer. (Pictured below left: The Tailor’s Family, c. 1920 by Marko Epshtein).

Delaunay was born in Ukraine but brought up in St Petersburg. In 1905 she moved to Paris where she became a mover and shaker in the art and design worlds and married Robert Delaunay. She stayed there until her death in 1979, by which time her importance had finally been recognised. On show is one of her gloriously colourful abstract paintings.

Tatlin, famous for his design for the Monument to the Third International, is not mentioned at all, even though he lived and studied art in Kharkiv and, from 1925 to 1927, was director of the theatre, film and photography department at the Kyiv Art Institute, which under the Soviets became one of the USSR’s leading art schools.

Tatlin, famous for his design for the Monument to the Third International, is not mentioned at all, even though he lived and studied art in Kharkiv and, from 1925 to 1927, was director of the theatre, film and photography department at the Kyiv Art Institute, which under the Soviets became one of the USSR’s leading art schools.

Malevich also taught at the Institute from 1928-30, by which time he abandoned Suprematism, the glorious form of abstraction that gained him an international reputation. Born in Kyiv, he studied drawing there, but moved to Moscow in 1904 where he developed his radical abstraction. On show is a landscape in the rather wooden figurative style he adopted after the Soviet authorities denounced abstract art as a bourgeois irrelevance.

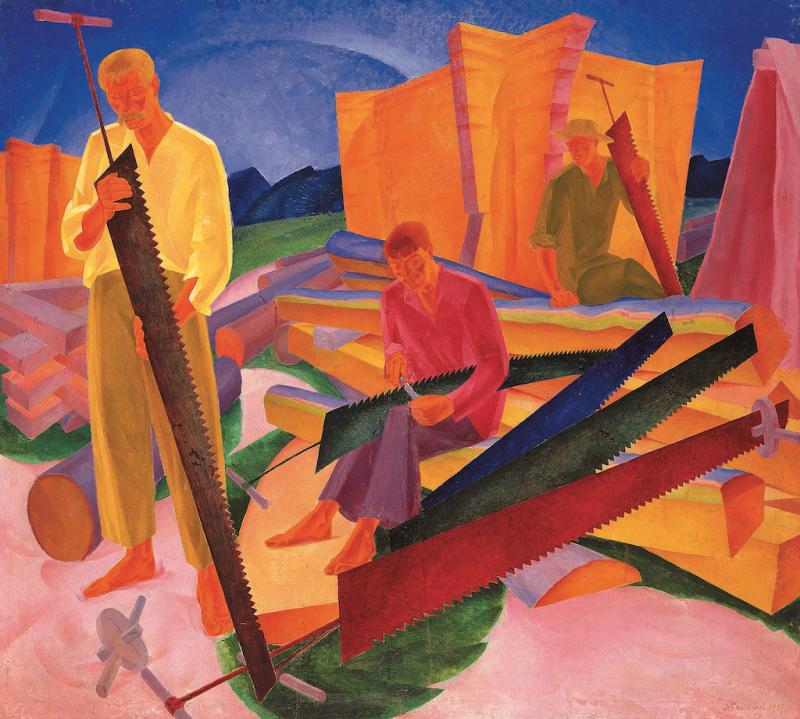

Despite his importance as a teacher and painter, Oleksandr Bohomazov (main picture) has only recently been rescued from obscurity. From 1922 until his death in 1930, he was professor at the Kyiv Arts Institute where his theories on art as outlined in his paper “The Art of Painting and the Elements” became part of the set course. Like Malevich, he tempered the abstract elements of his cubo-futurist paintings so as to avoid censure from the Soviet authorities.

They were right to be cautious. In 1928 and 1930 the Russian pavilion at the Venice Biennale hosted a group of Ukrainian artists led by Mykhailo Boichuk who created a fusion between folk art and geometric abstraction. Their acceptance was shortlived, though. Denouncing them as “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists”, Stalin had them all killed or sent to labour camps along with the writers, designers and directors of Kyiv’s theatre scene. Alexandra Exter had already defected to Paris and Davyd Burliuk to the United States. {Pictured below: Carousel, 1921 by Davyd Burliuk). The exhibition ends with examples of the tedious socialist realism imposed by Stalin as the official Soviet style. This modest exhibition is, then, both a revelation and a frustration. It whets your appetite for information about this fascinating subject but, with so few works on display by such major figures, it doesn’t begin to do justice to their inspiring achievements. Nevertheless, it makes the point that Ukraine deserves to be recognised alongside Paris, Rome, Moscow and St Petersburg, as a cradle of modern art.

This modest exhibition is, then, both a revelation and a frustration. It whets your appetite for information about this fascinating subject but, with so few works on display by such major figures, it doesn’t begin to do justice to their inspiring achievements. Nevertheless, it makes the point that Ukraine deserves to be recognised alongside Paris, Rome, Moscow and St Petersburg, as a cradle of modern art.

- In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine 1900-1930s at the Royal Academy until 13 October

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment