Remember when you were out playing football with your mates, and your dad pulled up beside the pitch in a slightly too flashy car and told you it was time for tea or – even worse – tried to join in the game – and how you died inside. Actually, I don’t remember this Nick Hornbyesque scenario, having spent most of my childhood avoiding playing football, but I certainly recognise the sentiment. I recognised it again the other day when I dropped my 13 year old daughter at a party, and she said through gritted teeth as we were arriving, “Don’t say anything!” In other words, don’t upstage me, don’t cramp my style, don’t stop me from being who I want to be.

No matter how much we love our parents, no matter how much we want to think well of them, even to feel proud of them, they inevitably cramp our style. And they keep on doing it from beyond the grave.

Our parents inevitably cramp our style. And they keep on doing it from beyond the grave

My father was an artist. No, that doesn’t make me feel proud. Those words have on occasion made me feel almost physically sick. My father was a larger-than-life working class hero who carved out a niche for himself in the history of Post-War British art. He was one of the people who modernised British art education, throwing out antique casts in favour of machines and new materials, creating an emphasis on problem-solving rather than learning time-honoured crafts.

As a child I was greatly impressed by him, believed everything he said unquestioningly; in adolescence and early adulthood, I spent much of my time trying to get as far away from him as possible. He was too forthright, too unyielding, too loud in his opinions. By the time I went to art school myself, in the mid-1970s, his brand of utopian Modernism was so out of fashion I found it hard to imagine it had ever existed. When I went for an interview at the college where I eventually did my degree, the Head of Printmaking said, "We had Edward Bawden ’s son here. His work was exactly like his father’s. Yours is nothing like your dad’s." I glowed with pride. My portfolio might have been downright pitiful, but at least it had nothing to do with HIM.

As a child I was greatly impressed by him, believed everything he said unquestioningly; in adolescence and early adulthood, I spent much of my time trying to get as far away from him as possible. He was too forthright, too unyielding, too loud in his opinions. By the time I went to art school myself, in the mid-1970s, his brand of utopian Modernism was so out of fashion I found it hard to imagine it had ever existed. When I went for an interview at the college where I eventually did my degree, the Head of Printmaking said, "We had Edward Bawden ’s son here. His work was exactly like his father’s. Yours is nothing like your dad’s." I glowed with pride. My portfolio might have been downright pitiful, but at least it had nothing to do with HIM.

How then did I come to find myself curating an exhibition of my father and his associates’ work?

When he died in 1997, I found myself taking stock – as people tend to on such occasions. Having spent most of the previous three decades trying to outdo him – fulfilling my creative potential in a way I felt he hadn’t quite fulfilled his, and making quite a good job of it, I thought – I now had to face the fact that whatever one might think of his historical role, at least he had one. It was one of those moments – quite gratifying at the time – when the son realises that the father is bigger than him.

Looking through my father’s papers at the National Art Education Archive, I found vast numbers of slides, films and photographs that would make the basis of a fantastic exhibition. But was I going to organise it? Was I hell? With the revival of interest in Modernist design, his structural reliefs, that had long looked merely cranky, now appeared almost trendy. I’d thought he’d blown his chances as an artist by spending too much time teaching, but with the rise of multi-disciplinary art, the idea of the artist-as-teacher and teacher-as artist felt very current. But I couldn’t afford to spend time promoting his legacy when I needed to create one of my own.

Then last autumn, my sister was clearing her cellar prior to moving, and found a piece of our father’s work. As soon as I pulled the sheet of plastic from the fibreglass relief I was transported straight back to 1965, when my father had assembled a group of young turk artists to realise his educational ideas, and we were living the Modernist dream in a house my father had co-designed on the beach near Cardiff. It was a moment when my childhood sense that everything was for the best in the best of all possible worlds happened to coincide with the high water mark of heroic Post-War optimism: a faith in technology and the future that was reflected in the bright colours and polished surfaces of my father’s work.

Rubbing off the decades of grime I saw that the brilliant blue and green surfaces still gleamed. It occurred to me that we could get a few other pieces of work together in a room, open a bottle of wine, and we’d have a modest little exhibition.

I went to see Michael Richardson, whose excellent Art Space Gallery in Islington has given shows to two of the artists my father worked with – Michael Sandle and Terry Setch. I went into that meeting with a vague idea about exhibiting a few bits of familial stuff. I came out the curator of an exhibition. I had no idea what I’d let myself in for.

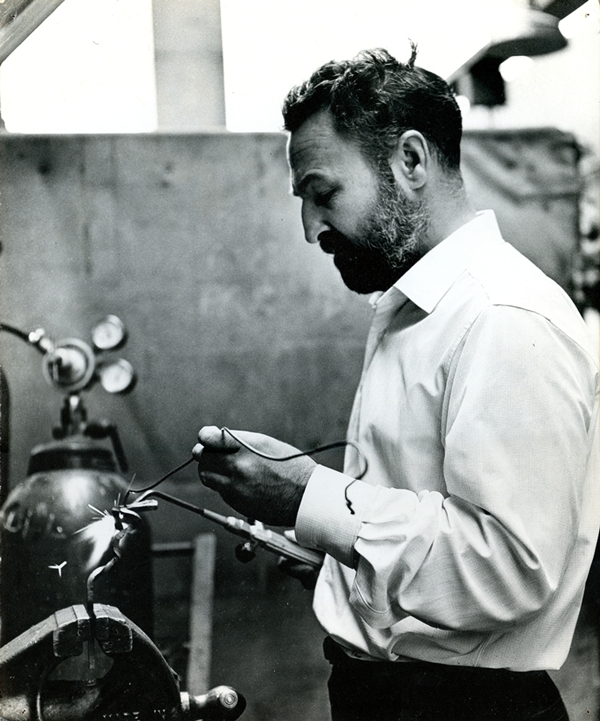

An exhibition has to have a coherent raison d’etre, a point to make, a story to tell, that will allow it to compete with all the hundreds, even thousands, of other exhibitions taking place in London alone at any one time. Michael and I hit on an idea relatively easily: centred on a photograph of my father and his colleagues in the so-called Leicester Group (left). Him and six younger artists, who all taught together at Leicester College of Art, looking young and bolshie. This we decided was an “iconic” image that represented a “moment” the world needed to know about: which would be all about the interaction of art and education in the heady Sixties.

An exhibition has to have a coherent raison d’etre, a point to make, a story to tell, that will allow it to compete with all the hundreds, even thousands, of other exhibitions taking place in London alone at any one time. Michael and I hit on an idea relatively easily: centred on a photograph of my father and his colleagues in the so-called Leicester Group (left). Him and six younger artists, who all taught together at Leicester College of Art, looking young and bolshie. This we decided was an “iconic” image that represented a “moment” the world needed to know about: which would be all about the interaction of art and education in the heady Sixties.

At first it was all good fun: persuading the surviving artists that it was worth being involved, getting together a body of work that would back up our thesis – and though it wasn’t yet 50 years ago, large amounts of work had been lost, particularly my father’s. Far from laughing in our faces, “people that mattered” were very encouraging. Yet the more it began to feel like a real exhibition, the more I was beset by a sense of visceral embarrassment at the idea of exposing my father – and myself alongside him.

I’d imagined some “expert” would write the catalogue essay, but of course it fell to me – there were no experts on this forgotten corner of British art history. Writing it took longer, per word, than anything I’ve ever written: trying to make it compelling without making one claim that was even slightly exaggerated. There was I felt a lot riding on this. If the show was a failure it would be an appalling embarrassment; if it was a success the implications were potentially even more onerous: I like to present myself as a maverick who owes nothing to anybody. Now in middle age, there was a chance I would be seen simply as the son of someone slightly well known.

By now some of the heavy hitters of the art world were coming out of the woodwork. “I didn’t realise Tom Hudson was your father,” said one. “That is major, major stuff.” But of course I had always suspected that.

As I walked towards the private view I realised that with the mad rush to get the exhibition installed, and my anxious ambivalence, I had failed to adequately publicise it. And now, of course, it was too late.

- Transition or The Inner Image Revisited is at Art Space Gallery, 84 St Peters Street, London N1 until 2 March.

Add comment