Samuel Takes a Break in Male Dungeon No 5 after a long but generally successful day of tours, The Yard Theatre review - funny and thought-provoking | reviews, news & interviews

Samuel Takes a Break... in Male Dungeon No. 5 after a long but generally successful day of tours, The Yard Theatre review - funny and thought-provoking

Samuel Takes a Break... in Male Dungeon No. 5 after a long but generally successful day of tours, The Yard Theatre review - funny and thought-provoking

'We don't use the word slave round here' - 21st century tourism skewered

You do not need to be Einstein to feel it. If the only dimension missing is time, 75% of a place’s identity can invade your very being, hollow you out, replace your soul with a void. It happened to me at Auschwitz and it’s happening to Samuel at Cape Coast Castle, Ghana.

Not at first. We meet him as our host, full of bonhomie, not just reading his script, but revelling in communicating his love of history to the tourists who come to the last staging post for slaves before the dreadful Middle Passage to the Americas.

Disillusion sets in. Some visitors are ticking off a bucket list, others vlogging to build their influencer profile and others going through a performative act of self-discovery. One or two are finding firm ground in a shifting, alienating world.

Samuel can’t. We learn that the place holds two traumas for him, two levels of abandonment, two histories overlaid, each invading his waking dreams. He needs that biscuit break in more senses than one, but where can he go, physically and psychologically? He has no home. If that makes Rhianna Ilube’s impressive debut play sound like hard work, I am misleading you. Her characters and dialogue sparkle with humanity and wit and, while the message hits and hits hard (Samuel is, obviously, a metaphor for Africa’s diaspora and migrants everywhere) there are plenty of laughs along the way.

If that makes Rhianna Ilube’s impressive debut play sound like hard work, I am misleading you. Her characters and dialogue sparkle with humanity and wit and, while the message hits and hits hard (Samuel is, obviously, a metaphor for Africa’s diaspora and migrants everywhere) there are plenty of laughs along the way.

Many spark from Orange, the 21-year-old ticket seller who aspires to be a television presenter or, failing that, a guide like Samuel. Bola Akeju times the wisecracks perfectly, and does some of her best work reacting with a flirtatious look or a quizzical smile or just a face that says “WTF!” at the parade of tourists who take the tour. It’s not that she doesn’t understand what Samuel is feeling, she just chooses not to, embracing a future untethered to the past – ever the privilege of youth.

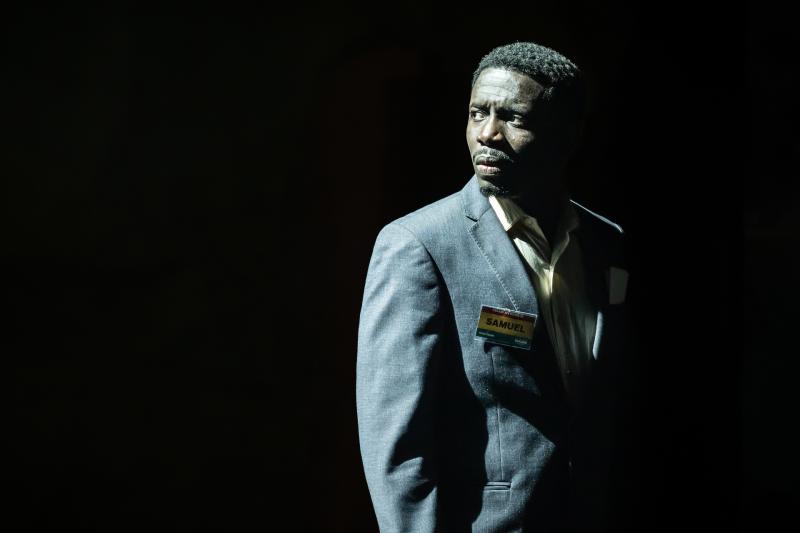

After a gruesomely hilarious turn as the YouTuber from hell, Tori Allen-Martin and Stefan Asante-Boateng (pictured above) leave the multi-rolling cameos and short scenes behind and play the parts of Letty and Trev, a mixed-race/Black British couple who aren’t really getting on at all. He is more interested in his phone and resents his wife’s fulsome embrace of her African roots (Letty grew up with her white father). She’s not sure what she wants or what she expects, but she is so keen to project her own neuroses on to the space that she never allows it to come to her.

These three performances are excellent, but the play can only succeed if its protagonist is comic and tragic, present and distant, wholly realised yet fatally incomplete. Fode Simbo is tremendous as Samuel, warm when acting as our guide, cold and introspective when taking his break, grounded when explaining what the place means to him, nightmarish when the ghosts in the walls invade his thoughts. It is a testament to the writing and Fode’s grasp of its intention that Samuel never becomes a caricature or a cypher, but never loses the sense that he stands for millions in his repressed agony.

Director Anthony Simpson-Pike keeps the pace high over 90 minutes all-through and there’s super work too from Christopher Nairne on lighting, slowly hemming us into the dungeons that are still incarcerating Samuel today.

This play hits the sweet spot with its engaging characters, its compelling story and its beautifully created sense of place. What lifts it beyond much that is available in London theatre now is its willingness to make serious, even essential, arguments about how the past infects the present without allowing he didactic to overpower the dramatic.

The door through which African men and women passed to be transported to the plantations was called “The Door of No Return”. Everyone who sees this play will return to its exploration of the price we pay to bury the past, and wonder how we can bear witness without damaging ourselves or sugar-coating our histories.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment