Charlotte Salomon: Life? or Theatre?, Jewish Museum London review - rallying against death | reviews, news & interviews

Charlotte Salomon: Life? or Theatre?, Jewish Museum London review - rallying against death

Charlotte Salomon: Life? or Theatre?, Jewish Museum London review - rallying against death

Set aside time to absorb the stunning work of this modernist painter murdered at Auschwitz

For a loved one to die by suicide provokes both pain and hurt. Pain, because they are gone. Hurt, because it can feel like an indictment or a betrayal. For Charlotte Salomon, the suicides that ripped holes in her family were also foreshadowings which provided the structure for her monumental cycle of narrative paintings Leben? oder Theater? (Life?

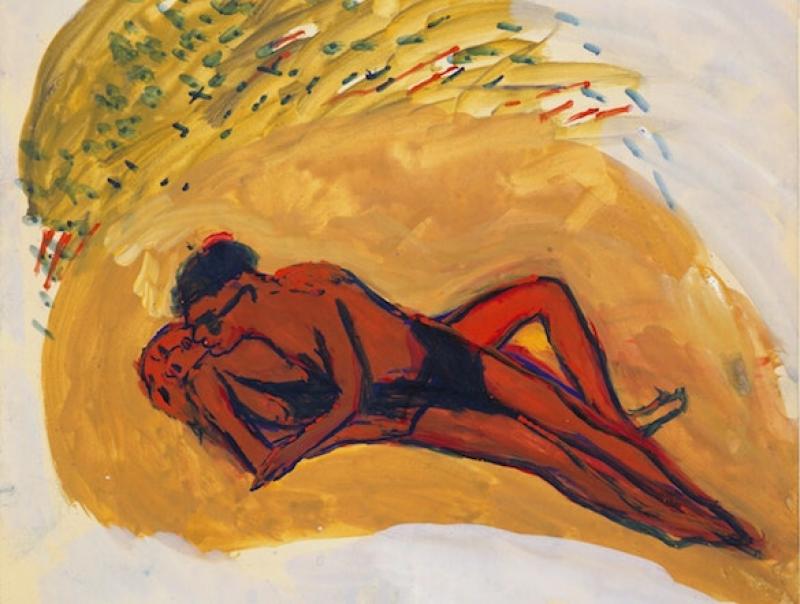

About a third of the 769 gouaches that Salomon selected of the roughly 1,300 she painted over the course of two years are displayed in the exhibition. Like the full work, and in keeping with her subtitle to the piece (Ein Singspiel, or A Song Cycle) the fictionalised account of her life opens with the suicide of her aunt Charlotte four years before her own birth and ends a little after her grandmother’s suicide — which she herself witnessed. Through a combination of words, text and musical references, using only three colours and a dizzying array of compositional methods, Salomon charts her progress from young girl to young woman and her growth as an artist. Alongside, she weaves in the stories of her family and associates, to whom she gives punning pseudonyms, including her first love Alfred Wolfsohn, who plays a principal role in the character of Amadeus Daberlohn (pictured top).

Their stories play out against the backdrop of the National Socialists coming to power in Germany (pictured below) and the tightening restrictions on freedoms for Jewish people. Yet though Salomon’s own life was under threat while painting the work — she composed Life? or Theatre? while in hiding in the Côte d’Azur in France — the dangers which in the work she dramatises herself as overcoming are more invidious. In total, ten members of her family — including her mother, aunt and grandmother — died by suicide and Life? or Theatre? stands primarily in defiance against what Salomon saw as one possible version of her own end. As Griselda Pollock writes in Charlotte Salomon and the Theatre of Memory, the acts of imagining and of painting became “a way of deflecting such a death”.

Their stories play out against the backdrop of the National Socialists coming to power in Germany (pictured below) and the tightening restrictions on freedoms for Jewish people. Yet though Salomon’s own life was under threat while painting the work — she composed Life? or Theatre? while in hiding in the Côte d’Azur in France — the dangers which in the work she dramatises herself as overcoming are more invidious. In total, ten members of her family — including her mother, aunt and grandmother — died by suicide and Life? or Theatre? stands primarily in defiance against what Salomon saw as one possible version of her own end. As Griselda Pollock writes in Charlotte Salomon and the Theatre of Memory, the acts of imagining and of painting became “a way of deflecting such a death”.

Salomon’s grandfather only revealed to her the true extent of her family’s history of mental illness after her grandmother’s suicide, but even before the Nazis upended her genteel life in Berlin, she was already fighting for her life on multiple fronts. Salomon was gripped with a sense of existential precarity and her sense of herself was so intimately tied up with her calling as an artist it seems to be only through her work she was able to recognise herself as a person capable of saying “I”. In one of her most gorgeous gouaches, where this sense of self and self-as-artist combine, she show herself three times, totally absorbed in her work at the Berlin art academy. Tulips, sunflowers and daisies fill the frame; there are vases, a child and a ball. Bright colours, a vivid sense of concentration and intense details show her flourishing, thriving.

Yet by her own admission, mustering this belief in her work was intermittent, hard won and came late. Given that the cycle may be described as a bildungsroman, it’s notable that the Haupttiel (or Main Action), which opens with Daberlohn’s entrance into her life, is ecstatically subtitled: “AND NOW OUR PLAY BEGINS!” While these five words mark the beginning of an important part of her life, they also suddenly and retrospectively categorise all the preceding years as artificial: she needed Daberlohn in order to feel herself as alive.

Yet by her own admission, mustering this belief in her work was intermittent, hard won and came late. Given that the cycle may be described as a bildungsroman, it’s notable that the Haupttiel (or Main Action), which opens with Daberlohn’s entrance into her life, is ecstatically subtitled: “AND NOW OUR PLAY BEGINS!” While these five words mark the beginning of an important part of her life, they also suddenly and retrospectively categorise all the preceding years as artificial: she needed Daberlohn in order to feel herself as alive.

It’s a troubling moment in the drama for it casts doubt upon how long this belief in herself — a version of which sustained her through the creation of Life? or Theatre? — would have endured. By the time Salomon wrote a passionate letter to Wolfsohn in February 1943, she had completed the work. Yet while she describes how his encouragement allowed her to believe in her art and therefore herself (“You said I was talented even though the whole world insisted the opposite […] you knew how – to give me a place in life.”) it’s clear from the very fact of composing the letter that she still needed him to be nurturing that belief. If her place in the world, after all, was given to her by him, she hadn’t yet created it for herself. Still indebted, her journey remained incomplete.

Nevertheless, the final painting of Life? or Theatre? (pictured above) is characterised by self-sufficiency. Salomon sits alone on a beach, her back to the viewer, beginning the very work that the gouache concludes. The sky is a deep, enduring blue. The artist is absorbed in her work. In the paintings directly preceding she claims to have realised she “did not have to kill herself like her ancestors.” Her justifications for living are still predicated on Daberlohn’s theories, not yet her own, but the humour, vision and self-reflection which characterise the work suggest a sense of purpose, confidence and great artistic conviction. What the future would have held is impossible to say, however. Six months later, aged 26 and five months pregnant, she was murdered upon arrival in Auschwitz. Her marvellous work now stands testament not just to her talent and resilience, but also her betrayal. Not by fate, but by history.

Nevertheless, the final painting of Life? or Theatre? (pictured above) is characterised by self-sufficiency. Salomon sits alone on a beach, her back to the viewer, beginning the very work that the gouache concludes. The sky is a deep, enduring blue. The artist is absorbed in her work. In the paintings directly preceding she claims to have realised she “did not have to kill herself like her ancestors.” Her justifications for living are still predicated on Daberlohn’s theories, not yet her own, but the humour, vision and self-reflection which characterise the work suggest a sense of purpose, confidence and great artistic conviction. What the future would have held is impossible to say, however. Six months later, aged 26 and five months pregnant, she was murdered upon arrival in Auschwitz. Her marvellous work now stands testament not just to her talent and resilience, but also her betrayal. Not by fate, but by history.

- Charlotte Salomon, Life? or Theatre? is at the Jewish Museum London until 1 March 2020

- Read more visual arts on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment