'That brick red frock with flowers everywhere': painting Katherine Mansfield | reviews, news & interviews

'That brick red frock with flowers everywhere': painting Katherine Mansfield

'That brick red frock with flowers everywhere': painting Katherine Mansfield

Anne Estelle Rice painted the New Zealand writer 100 years ago, spinning a tale of love, friendship and artistic kinship

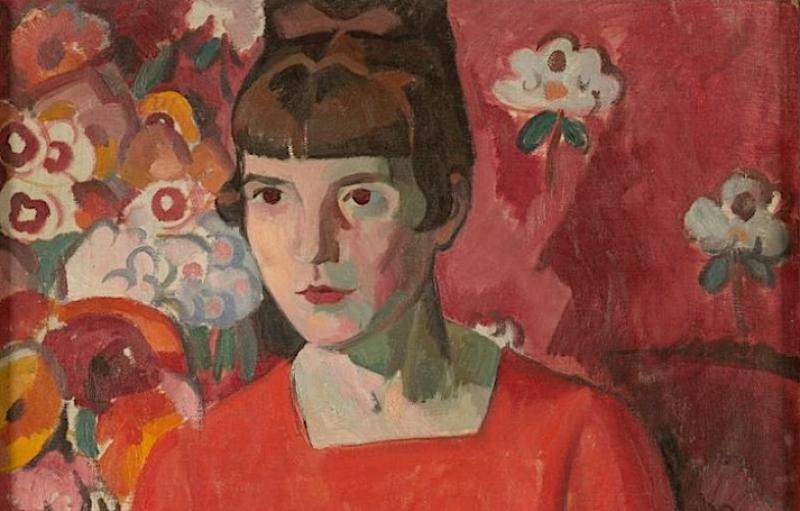

The well-known portrait of New Zealand’s greatest writer, Katherine Mansfield, is exactly 100 years old on 17 June 2018 (main picture). It was painted by the American artist Anne Estelle Rice.

In December Mansfield had been diagnosed with tuberculosis, at that time incurable, and from which she died five years later, but in May, her very brief marriage to George Bowden having been terminated, she married writer-editor John Middleton Murry. Mansfield and Murry were to have a highly unusual relationship, notable not only for its frequent and lengthy partings. Katherine was in Cornwall without him, with the aim of resting in the fresh seaside air. We know the date of the sitting from a letter that Katherine sent to her husband in London on 17 June:

Anne came early and began the great painting – me in that red (sic) brick red frock with flowers everywhere. It’s awfully interesting even now.

That last phrase implies that there were to be later sittings, but, if there were, Mansfield did not mention them in surviving letters or notebooks. Nevertheless, the fact that it was not finished is evident from a meeting between Mansfield’s first biographer Ruth Mantz and Rice in 1933, where Mantz encouraged the artist to complete it. In fact, there had been an earlier sitting at Looe, Katherine reporting to Murry on 29 May that "Anne is painting me and old Rib – Rib of course – is violently flattered and keeps flattening down his fringe at the thought". Rib is Katherine’s Japanese doll, who makes an appearance in several letters. This earlier effort may have been a sketch for the 17 June portrait.

Mansfield was not enamoured with life in hotels: "I seem to spend half my life arriving at strange hotels," she wrote, "and asking if I may go to bed immediately." Katherine’s friend and rival Virginia Woolf, writing to their friend Ottoline Morrell on 24 May noted: "I saw Katherine Murry the other day – very ill, I thought …". Rice seems to have come to visit Katherine at the Headland Hotel on an almost daily basis, and she appears regularly in Mansfield’s letters and notebooks, in which Katherine posted two paragraphs entitled ‘Pic-Vic’, as if the possible beginning of a new short story:

Mansfield was not enamoured with life in hotels: "I seem to spend half my life arriving at strange hotels," she wrote, "and asking if I may go to bed immediately." Katherine’s friend and rival Virginia Woolf, writing to their friend Ottoline Morrell on 24 May noted: "I saw Katherine Murry the other day – very ill, I thought …". Rice seems to have come to visit Katherine at the Headland Hotel on an almost daily basis, and she appears regularly in Mansfield’s letters and notebooks, in which Katherine posted two paragraphs entitled ‘Pic-Vic’, as if the possible beginning of a new short story:

When the two women in white came down to the lonely beach – She threw away her paintbox – and She threw away her notebook. Down they sat on the sand. The tide was low. Before them the weedy rocks were like some herd of shaggy beasts huddled at the pool to drink and staying there in a kind of stupor.

Then She went off and dabbled her legs in a pool thinking about the colour of flesh under water. And She crawled into a dark cave and sat there thinking about her childhood. Then they came back to the beach and flung themselves down on their bellies, hiding their heads in their arms. They looked like two swans.

In Rice’s portrait of Mansfield, the contrast between the colourful flower-filled background and Mansfield’s "brick red" dress, and the serious, intense expression on her face is striking. This is no warm, cuddly representation of the writer, rather a representation that underlines Katherine’s seriousness. At the same time, the light streaming in from the left leaves the right side of her face highly illuminated with the left side in relative darkness, the shadow, together with the yellow on her cheek, signalling her recently-diagnosed TB. The floral background to the portrait is not easy to read – not least the flowers themselves. Those to the left of the sitter are a mixture in a vase, whereas those to the right are decoration on wallpaper or curtain material. Mansfield sits in an armchair, her hands, crossed on her lap and holding a book, all indicated by mere slabs of paint.

Although Katherine was attracted to the artist, Rice and Mansfield were not likely to become loversAnne Estelle Rice had first met Murry at the Café d’Harcourt in the Boulevard St Michel in Paris in 1910. At that time Anne lived with the Scottish painter John Duncan Fergusson, who recalled that he and Anne had "sat beside a very good-looking lad [Murry] with a nice girl ["Yvonne", Murry’s current girlfriend]." Murry first met with Mansfield late the following year, and Murry soon introduced Fergusson and Rice to Katherine (Pictured above right: JD Fergusson, Anne Estelle Rice in Paris (Closerie des lilas), 1907. She and Anne were to become close friends through the rest of Mansfield’s life, although Rice is only mentioned in passing in the many biographies of the writer. Mansfield dedicated her New Zealand story of 1912, "Ole Underwood", to her, Katherine summing up her warm feelings for Anne in a letter to Murry on 23-24 May:

Drey and Anne came last evening and we sat up late talking of Anne’s life … You know she is an exceptional woman – so gay, so abundant, in full flower just now and really beautiful to watch. She is so healthy and you know when she is happy and working she has great personal "allure" – physical "allure" ‒ I love watching her.

Mansfield concludes this passage by reassuring Murry: "Of course she is not in the least important." Perhaps this was a coded message to him that, although Katherine was attracted to the artist, Rice and Mansfield were likely neither to become lovers, nor to intrude in their relationship. In a later letter to Rice (26 December 1920), Katherine makes clear her admiration of the artist: "Whenever I examine things here – the lovely springing line of flowers and peach leaves par exemple, I realise what a marvellous painter you are – the beauty of your line – the life behind it."

Eleven years older than Mansfield, Anne Estelle Rice was born in 1877 at Conshohocken, a mill town near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, then grew up at Pottstown, some 50 kilometres away. She was said by her husband to be of Scottish, Irish and Pennsylvania-Dutch descent. From 1894 she studied art for three years at the School of Industrial Art in Philadelphia before going on to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where she studied with William Merritt Chase and others.

Even in her student years, she was contributing fashion illustrations for Collier’s, Harper’s and the Saturday Evening Post, before moving to Paris in 1905, where she worked for Philadelphia’s North American magazine. At Paris-Plage (now Le Touquet) on the Normandy coast two years later, she met and formed the close relationship with John Duncan Fergusson, who introduced her to the Fauvists.

The aesthetic concept of "rhythm" provided the connective tissue between the writers and artists involved with the magazineJD Fergusson has come to be associated with three other Scottish painters with similar artistic aims – Samuel John Peploe (who joined them in Paris in 1910), George Leslie Hunter and Francis Cadell – now together known as the Scottish Colourists. In recent years they have become well-known and popular, particularly in Scotland. Rice could well be a member of this group, her work being closely in tune with theirs, but for the fact that she was American, not Scottish. The Colourists were influenced by a range of earlier French artists, among them Realists, Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, but most immediately by their Fauvist contemporaries ‒ Matisse, Derain, Marquet and others ‒ and also the young Picasso and Braque. At the heart of the Colourists’ oeuvre was a fascination with French culture, which deeply influenced their work.

What brought the four of them together professionally ‒ Murry and Mansfield, Fergusson and Rice ‒ was Murry’s new literary and arts quarterly Rhythm (later called The Blue Review). Launched in the summer of 1911, the magazine was edited by Murry, with Mansfield as assistant editor (until June 1912) and Fergusson as art editor. Rice provided illustrations (and an article on Diaghilev’s Russian ballet in Paris), while Fergusson contributed the cover. Other notable contributors included Max Beerbohm, Frank Harris, Walter de la Mare, DH Lawrence (in The Blue Review) and Rice’s husband, Raymond Drey.

The aesthetic concept of "rhythm" ‒ harmony in nature, vigour and directness ‒ provided the connective tissue, not only between two Scottish Colourists (Fergusson and Peploe, plus Rice), but also between the writers and artists involved with the magazine. "We must be ferocious, merciless, pitiless," wrote Murry, "tearing at all before us." Lawrence and his wife Frieda became close friends with Mansfield and Murry, and in Women in Love Lawrence adapted an anecdote which Katherine had told him about a party at Rice’s Paris studio in Montparnasse, which opens:

"What did you do in Paris?" asked Ursula [Frieda].

"Oh," said Gudrun [Mansfield] laconically – "the usual things. We had a fine party one night in Fanny Rath’s [Rice’s] studio."

"Did you? And you and Gerald [Murry] were there! Who else? Tell me about it."

In Paris, Rice exhibited first in the Ashnur Gallery, then from 1908 to 1913 (the period of her close association with Fergusson) at the Salon d’Automne and at the Salon des Indépendants. In London, she showed at the Baillie Gallery in 1911 and 1913. New Zealand-born John Baillie moved to London in 1897, and by 1901 was including the work of fellow New Zealander Frances Hodgkins in his exhibitions. In their six years together, Fergusson painted portraits of Rice frequently. Many of these feature the bold outlining, bright colours and floral backgrounds present in Rice’s portrait of Mansfield.

Rice and Fergusson’s relationship ended when Fergusson met the dancer Margaret Morris in 1913, who was to become Fergusson’s partner for the rest of his life. Rice and Drey lived in England following their marriage. Through the 1920s and 1930s she was drawn strongly to the theatre and opera, designing both costumes and sets for a range of productions, including Walter Leigh’s Jolly Roger with George Robey in the lead, and Peter Garland’s Basilik with Paul Robeson and Coral Browne, while she continued to paint. Aged 82, she died in 1959.

- Anne Estelle Rice’s Portrait of Katherine Mansfield has been a prized part of the National Art Gallery collection in Wellington (now the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) since January 1946.

- Roger Neill is an arts historian who works on Australasian and other artists, musicians and writers of the fin de siècle

- Read more features on theartsdesk

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Comments

Gabino Amaya Cacho is the

The painting had an outing at