Tim Wardle: 'A documentary director has huge power over the interview subject' | reviews, news & interviews

Tim Wardle: 'A documentary director has huge power over the interview subject'

Tim Wardle: 'A documentary director has huge power over the interview subject'

Director of Three Identical Strangers on the most successful UK-made documentary in American box office history

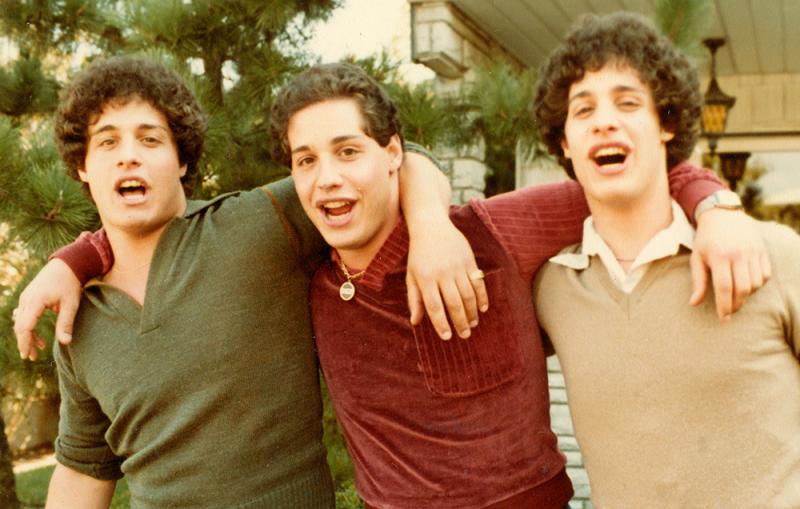

(Warning: spoilers ahead) For a brief 15 minutes, this was the biggest story in America: three boys, identical in looks, discovering each other at the age of 19. Edward “Eddie” Galland, David Kellman and Robert “Bobby” Shafran were all adopted from the same agency, but had no idea they were triplets.

Then, as quickly as it came, the attention disappeared, but this was only the beginning of their story. In the years that followed, the circumstances behind their split came to light. The agency assured the adoptive parents that it was because placing triplets was much more difficult, but there was a more menacing objective.

The agency was approached by leading psychiatrist Dr. Peter B. Neubauer with an intriguing proposition: what if we could definitively prove whether our personalities were influenced primarily by nature or nurture? The results dould fundamentally change our understanding of the human condition, and so these baby brothers were split 6 months after birth, and placed in families with vastly differing incomes and parenting styles. Then, they were covertly monitored over 20 years.

The full extent of the research and its outcomes have never been made public. For the brothers, it has been a dark cloud over their entire lives. After the suicide of Eddie, David and Bobby have barely stayed in contact. That is until a British filmmaker got in contact about telling their story and, possibly, finding some definitive answers behind the Neubauer experiment.

Three Identical Strangers releases in the UK this Friday, but has already become a major hit in the US. It’s an engaging and at times shocking look at what makes us human, serious in tone but told with style. Owen Richards spoke with director Tim Wardle about how he gained the trust of surviving triplets David and Bobby, to finish telling the world their story.

OWEN: How much were you aware of the triplets’ story ahead of choosing to film?

OWEN: How much were you aware of the triplets’ story ahead of choosing to film?

TIM: When I first heard about the idea, I’d never heard it before, and I kind of couldn’t believe that. Part of my job is to be across pop culture, and all these stories from the 80s and 90s; I also did psychology in university and thought: how have we not heard of this?

In the four years it took to develop it, to get the brothers on side, to get the money together, and by that point I knew about 50-60% of their story. That was the backstory, I didn’t have all the details but I had a broad overview of that. One of the huge challenges of getting funding for the film was funders asking “what’s the third act? Where does it go?” and I said I didn’t know. We were going to try to leave the study open, try to get answers for the brothers and get some justice for them. Find answers to these mysteries that have alluded them for about six decades. But we really didn’t know.

A lot of things that are in the film, we had no idea we’d get when we set out: interviews with key people we didn’t know existed, twists in the story we didn’t know were there. It was a real journey of discovery making this film, and it strikes me the thematic arc of the film is nature versus nurture – me and my producer really went on a journey making the film. It challenged us, every interview we did changed our mind on where we stood on nature versus nurture.

The film starts of quite upbeat, and then goes deeper and darker down the rabbit hole. Did you always expect it to go like that?

Because I knew enough of the backstory, I knew it would modulate in tone. A lot of films, both drama and doc, they establish a tone at the start and then stick with it. We always knew it would start out like a John Hughes film, or like one of those 80s body-swap comedies, and then it would modulate into something more serious and darker – more like an identity thriller.

I suppose I always imagined it being partially about the boys’ quests for identity, who they are and why they’ve come to the place they have. I didn’t think we’d end up as journalistic as we did, and that’s mainly due to the producer Becky Read trained as a journalist. She did an incredible job turning up stuff and ultimately getting a hold of these secret archives that hadn’t been seen until the very end of the film.

What was it like first making contact with Bobby and David? How did you build that trust?

It was pretty nerve wracking. It took four years – I got engaged, married and had two children in the space it’s taken to make this film – mainly because they don’t trust people after what happened to them, and you understand why that is. They’d also been promised a lot when they had their 15 minutes of fame in 1980, people saying “we’ll make a movie out of your story” and all this kind of stuff. They didn’t trust us, they weren’t really speaking to each other, their relationship was very fractured, and it just took a long long time.

The honest truth is the first conversations were incredibly difficult and unproductive. I think it helped being British, I think they were a bit intrigued why British people would be interested in this story, and that helps being an outsider making a documentary. It was a real challenge and definitely wasn’t an easy relationship at the start.

Their fractured relationship really showed when they finally get together on camera. Did you see that change through filming?

Their fractured relationship really showed when they finally get together on camera. Did you see that change through filming?

It was definitely very awkward when we got them together. They really weren’t talking at that point. Since the film’s come out, they’ve spent a lot more time together, and I think the experience of people recognising their story and what was done to them has brought them together. I think they very much describe it as a work in process, but it’s much closer than it’s been for a long time, which is great and unexpected. We didn’t set out to bring them together for the film, but that’s what happened.

As the film develops, it moves from retelling the story into a search for the truth. Was that from your own curiosity and need of closure, or was that driven by David?

It was a combination of both of us. As we say in the film, initially when they first got together they weren’t really interested in the circumstances of their separation because they were too busy having a good time. After the tragic events of their lives, they didn’t even want to engage with it because it was too painful, so I think now they were coming around to the point where they were hunting for answers and they did want to know what happened.

Through a combination of us pushing gently for answers and them actively wanting to do it themselves, David was the driving force, but it was a joint effort. Certainly we couldn’t have got access to this secret archive without their involvement and co-operation.

There are times when it gets pretty intense, whether it’s talking about Eddie with the other brothers, or discussing ethics with the researchers. How much did you keep a distance?

As a director I’ve never really had a problem with that, I think that’s par for the course doing a documentary. What you’re looking for is an emotional truth, and you’re upfront with people at the start saying “we’re going to have to talk about some stuff you’d probably rather not talk about” but it’s really important because that’s how an audience connects with a film. They don’t connect because they’re being told a load of information that’s factually correct and in the right order (which is obviously very important), they emotionally connect with the person and the feelings that they’re displaying.

One of the things I always wanted to do was tell it from their perspective. In the film, you see most of the things from the brother’s perspective. Information is revealed to the audience as it was revealed to them. When there are shocking twists, the idea was to make the audience feel like they felt when they suddenly found out that information for the first time. I very much wanted the audience on side, so when difficult stuff came up, we felt really invested because we were experiencing it with them, as opposed to more vicariously going: look at some person that’s upset. Here you’ve been with this person on the journey since the start of the film, so we really care about what you’re talking about.

In terms of directing technique, the important thing is building up to the difficult stuff, and then you build down from it too. You don’t end on the most emotional stuff and then say “right thanks, bye!” You have to take them out of it as well, so I quite often go back to talking about the happier times in their lives when they were first reunited before the interview ended, so I wasn’t leaving them in place where they were really distraught.

I think those documentary ethics are really important. Just as a scientist in the film has huge power over their subjects when doing research, so a documentary director has huge power of the interview subject. You can put a camera one someone and ask them pretty much anything, and most people will tell you. You have to be really mindful of how you use that power. I think rather than be worried about myself and keeping some distance when interviewing some people, I’m being really conscious of them and their mental state, and how this interview is going to affect them. I try to keep conscious of that all the way through. You let the families tell their story, but do you have your own views on the actions of the adoption service and Dr Neubauer?

You let the families tell their story, but do you have your own views on the actions of the adoption service and Dr Neubauer?

I do. I mean, I’m really interested in the grey areas of human behaviour – why decent people, which definitely the scientists were, do bad things. I’m much more interested in that than black and white, “they were evil/they were good” versions of humanity. I feel that they started out doing this thing with a combination of really good intentions and also a bit of ego – like “wow if we can definitively prove this one way or the other, nature versus nurture, we’ll be the most famous scientists ever,” and along the way they lost sight of the ethical and human implications of what they were doing.

I think the historical context is really important. In the 50s and 60s, it was sort of the wild west of psychology, and there were lots of experiments done then, like the Milgram Obedience Experiment, and later the Stanford Prison Experiment. They would never get past an ethics committee in a psychology department today. The context is important, but I also think they had an inkling that it was ethically suspect at best because they approached a lot of other agencies and were told you can’t do this, you can’t separate children. So it’s not like they didn’t have some sense that some people think this is wrong.

You use a lot of different techniques in the edit to achieve the emotional impact of the story, what was the edit process like once you got the materials?

I should start by saying for everyone that worked on this film (apart from the executive producer), this was their first feature documentary. Most of us had made TV documentaries before but this was a real step up, and that includes the editor Michael Harte.

We had a good plan going into the edit which always helps. He cut the entire thing in 18 weeks which for a documentary of this type is just extraordinary. Most people take about a year to edit films this long and with this much material, so he did an amazing job working incredibly hard.

As I mentioned before, we were conscious we were going to have these tonal shifts, and so we watched really weird things for reference points. We watched the Michael J. Fox film The Secrets of My Success for the 80s section, and then we were watching the Bourne films for the later bits when talking about narrative influences. There are these parallels between Bourne and the brothers, it’s about someone searching for their identity, involuntarily part of a secret experiment.

I think that the film contains a lot of different documentary filmmaking techniques, it’s kind of a love letter to all the filmmakers that I admire and the filmmakers I’ve worked with myself in the past. There’s elements of Errol Morris, elements of Michael Apted’s 7 Up, elements of Joe Berlinger’s Paradise Lost, the reconstruction that Bart Layton did on The Imposter.

I see documentary as a really broad church, and some people see documentary in very black and white terms. There are purists who feel like a documentary has to be a certain way, some believe it has to be completely dispassionate and just facts with no emotion. I really reject that, I think it can be all manner of things and have a variety of influences is a really good thing for a film.

It’s interesting you say that you watched films like Bourne, because there were moments watching it where I’d suddenly put the pieces of the plot together as if it was a thriller.

Yeah, I love films where information is seeded earlier and it pays off later on! It’s was there right from the start, so if you were paying attention, you see it pay off later. I love that in films, it’s not just “here’s a new thing, and here’s a new thing,” it’s “here’s something we mentioned before, but you can see it in a different context.” I think that’s where the influence of my love of drama and scripted techniques is visible in the film.

At the end of the film, it says that they’ve been granted access to the research. Do you know if they’ve found any answers?

At the end of the film, it says that they’ve been granted access to the research. Do you know if they’ve found any answers?

What happened right at the very end of the film, my producer and the brothers got access to their files. They’re very heavily redacted, they were given about 11,000 pages, and all the names of the other people involved have been cut out.

There are a few details: the first thing to say is that there are no formal conclusions, it’s more like here are our findings and what we’re thinking about this, but they never summarise or find hard conclusions. There’s a lot of notes of scientists sitting around in meetings discussing what the research might mean. It’s a weird mixture of really hard scientific research, and a lot more psychobabbly stuff.

One of the more tragic details in there was Eddie was adopted by another family before he was adopted by his eventual family. It was a failed adoption and he was given back to the agency. We didn’t know that while we were making the film and you wonder what impact that had on him.

There were details like that, and there’s a lot of scientists sitting around saying “all the kids in this study seem to have behavioural issues or problems, I wonder why that is?”, speculating whether it was due to forceps in the delivery or whatever, as opposed to going “maybe it was us and the act of separation that caused all this.” There’s a remarkable lack of insight, maybe intentionally so they could deny it in the future because they knew notes were being taken of these meetings.

One shocking detail as well was that around 1970 all the parents of the boys separately said “they don’t want to do this anymore, can you stop coming?”, and what’s clear is the scientists carried on studying them from afar and still making notes of them way into the late 80s, after their reunion. I find it extraordinary since they specifically asked not to be a part of it any more. But yeah, there’s a lot of detail in there but there’s nothing concrete in the findings of the experiment.

It’s quite ironic that in the film one of the scientists claims that all the research was pointing towards nature being the overwhelming driver, but the access and oversight you had points to a very different conclusion.

At the start of the experiment in the 60s, it was generally believed that nurture was really dominant. That was the political ideology of the day, and people felt children were blank slates and you could raise a child from the most deprived background to be an astronaut. They assumed something like 90% was nurture, but the study showed that nature was much more powerful than they realised. I think even nature being a 50% would be totally mind blowing for them. What she said still holds water. We’re just saying in the film that both are important.

It shocked me how important nature and DNA are in making us who we are, even though the film ultimately says nurture was really important too. They’re both right: she was right that nature was way more than they were expecting and it’s scary how powerful your genes are, but other people in the film are right that ultimately nurture is really important too. I think the older the brothers have got, the more that the nurture has shown through.

What was the feedback from the families on the finished film?

They have all pretty much loved it. I guess obviously the most difficult viewing was with Eddie’s father, and one of his daughters was there, but I think he liked it over all. I wasn’t there, my producer showed it to him, and apparently he said “good job kid, when are we going to the Oscars?”

It was interesting with the brothers. I showed it to David and Bobby separately, and they both loved the film, but the real emotional response I had from them was “you did what you said you were going to do.” I realised at that point, for the first time in five years of working with them, that so many people had let them down that just the act of following through and doing what we said we’d do, making this film and doing it in this way, that was the biggest deal for them. I guess I wasn’t prepared for that, I didn’t realise it would have such a strong impact for them. It was great, and I’m thrilled that they loved it and we’ve had the extended family come to a number of screenings, and the response has been great

As shown in the film, they were absolutely everywhere in the US media at one point. What has been the public reaction to their story coming back?

The first thing I should say is it’s pretty much the most successful UK-made documentary in the American box office ever. I think it’s made about $12.3 million, the next most popular was Amy which got $8 million, so it’s exceeded our expectations, especially because a lot of the documentaries that do well have famous people at their heart. People turn up to see a documentary about Quincey Jones or a big political figure, so that was quite surprising and lovely.

The brothers were really well known in the 80s briefly, but weirdly most people in America don’t seem to remember them. Occasionally someone will say “oh yeah vaguely, those brothers who separated and found each other.” No-one knows the full extent of the story out there.

What it has clearly is really good word of mouth. We just thought it was this little film that we made and were proud of, and it went completely crazy over there. It’ll be interesting to see how a British audience respond to it, because you could think it’s a very American story. I’ve always felt it’s a universal story and a story that people like to talk about. Certainly, at the small number of screenings we’ve done in the UK so far, afterwards people really want to talk about it. I’m hopeful it has a similar response here, but certainly over there, despite not having the recognition of the story you might imagine because most people had literally forgotten about it, it just took off and it has been completely unexpected and the most crazy year ever.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Add comment