Picasso 1932: Love Fame Tragedy, Tate Modern review - a diary in paint? | reviews, news & interviews

Picasso 1932: Love Fame Tragedy, Tate Modern review - a diary in paint?

Picasso 1932: Love Fame Tragedy, Tate Modern review - a diary in paint?

Biography prevails in a compelling account of the artist's year of wonders

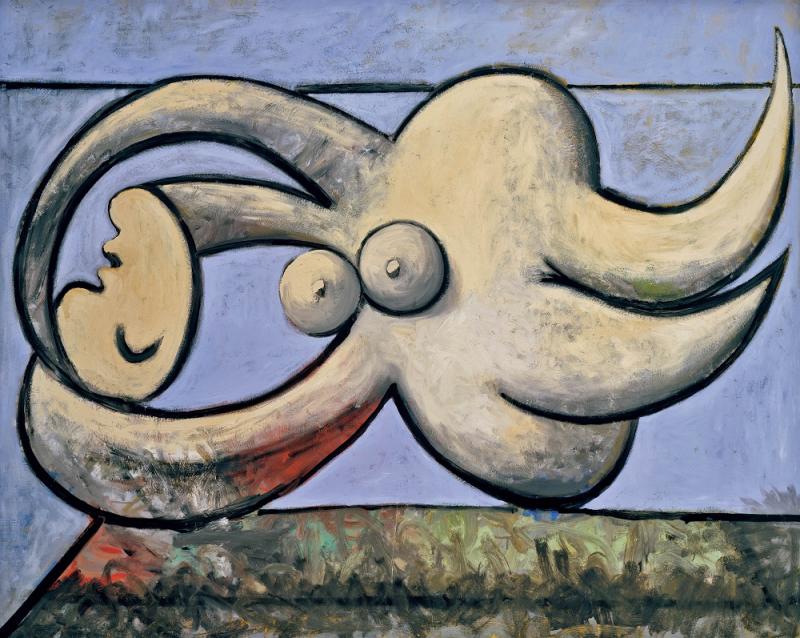

Painted in ice-cream shades punctuated with vivid red, the series of portraits made by Picasso in the early weeks of 1932 are as dreamy as love letters. His mistress Marie-Thérèse Walther – we assume it is she – lies adrift in post-coital languor, her body spread before us as a delicious and endlessly fascinating confection.

In Sleeping Woman by a Mirror, Marie-Thérèse’s bright yellow hair is now an ashen grey, her face cracked open like an egg, her arm lying limp across a construction that is at once her lap, and her breast, and a monstrous phallus. Love seems so easily to have fallen into decay and violence. We are drawn into a hopelessly literal way of looking at these pictures, encouraged both by Picasso’s handy comment that “the work that one does is a way of keeping a diary” and the curators’ decision to present these paintings as if they are pages in a journal. Dated by day, they suggest a ferocious work rate fuelled by his intense affair with Marie-Thérèse. Picasso’s system for dating works is unknown: that he probably dated them when finished, thus giving no indication of a start date, is mentioned but not allowed to spoil a good story.

Cultivating tabloid appeal – Love, Fame, Tragedy – while aiming to satisfy standards of academic probity, the curators at Tate Modern are pulled hard in two directions, evident in lukewarm warnings against overly biographical interpretations. Woman with Dagger, painted over Christmas 1931, is often treated as an expression of his strained relationship with his wife, Olga. Here though, we are advised to see it less as a therapeutic release, and more as an indication of Picasso’s interest in surrealist preoccupations, which emerges in his work from this time as a distinct and opposing tendency to his interest in colour and form.

Cultivating tabloid appeal – Love, Fame, Tragedy – while aiming to satisfy standards of academic probity, the curators at Tate Modern are pulled hard in two directions, evident in lukewarm warnings against overly biographical interpretations. Woman with Dagger, painted over Christmas 1931, is often treated as an expression of his strained relationship with his wife, Olga. Here though, we are advised to see it less as a therapeutic release, and more as an indication of Picasso’s interest in surrealist preoccupations, which emerges in his work from this time as a distinct and opposing tendency to his interest in colour and form.

Such tensions culminated in 1932: an annus mirabilis for Picasso according to his biographer John Richardson, during which he produced some of the most significant work of his career. The need to reconcile his by now stellar reputation with his place at the cutting edge, his dual interests in surrealism and coloration, sculpture and painting, all form counterpoints in a period of astonishing creativity galvanised by the energising effects of an affair that itself stood in marked contrast to his 13-year-long marriage.

If Marie-Thérèse, so readily identifiable by her blonde hair and prominent Roman nose, is everywhere here, the much-maligned Olga is consigned to the shadows, emerging halfway through in a partial reconstruction of the Picasso retrospective held in Paris in June 1932. Here Picasso’s most famous – though certainly not his most vicious – portrait of his wife, painted in the classicising style typical of his work in the years after the First World War, is surrounded by portraits of their children, notably Paulo as a Harlequin, 1924. Cast as a matriarch, Olga’s restrained elegance contrasts uncomfortably with the luscious extravagance of Marie-Thérèse.

The retrospective marks a highpoint in Picasso’s year, after which the playfulness and joy of the early months seems gradually to dissipate. Brightness and light give way to monochrome in studies of the crucifixion after Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, 1512-16, and a preoccupation with death by water. Sheer erotic force is replaced by something more ambiguous as the female figure transmutes into the watery shape of an octopus. It’s a fairly subtle shift, and not always a repulsive one, the flipper-like hands sometimes only intensifying the sense of Marie-Thérèse as an otherworldly creature, capable of metamorphosis. Bathed in cool blue light, she becomes a moon-goddess once more in Nude Woman in a Red Armchair (pictured left) from the summer; elsewhere a creature more like a mermaid is invoked.

The retrospective marks a highpoint in Picasso’s year, after which the playfulness and joy of the early months seems gradually to dissipate. Brightness and light give way to monochrome in studies of the crucifixion after Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, 1512-16, and a preoccupation with death by water. Sheer erotic force is replaced by something more ambiguous as the female figure transmutes into the watery shape of an octopus. It’s a fairly subtle shift, and not always a repulsive one, the flipper-like hands sometimes only intensifying the sense of Marie-Thérèse as an otherworldly creature, capable of metamorphosis. Bathed in cool blue light, she becomes a moon-goddess once more in Nude Woman in a Red Armchair (pictured left) from the summer; elsewhere a creature more like a mermaid is invoked.

The trouble is that the biographical narrative of the hang overpowers any efforts to remind us that Picasso was responding to an artistic imperative, for all his talk of paintings as pages from a diary. We may be reminded to look with eyes informed by his interest in Japanese erotica, and the dark urges of the subconscious so fascinating to surrealist artists, but such attempts fall flat. Heightened by the show’s storytelling power, the temptation becomes overwhelming to see his reclining nudes from the summer of 1932, in which limbs curl and twist like the tentacles of an octopus, as symptomatic of his state of mind, and by extension the state of his domestic arrangements.

Lost in the seductive thrill of biography is the question of artistic identity, as it applies both to Picasso, and his muse. Because while it is deeply misleading to consider these paintings to be about – and only about – Marie-Thérèse, it is equally clear that without her, this work could not have been made. The exhibition’s great centrepiece is a room dedicated to the series of monumental nudes painted in March of 1932: proof, according to Picasso’s awestruck dealer, that painting was not dead. Ostensibly, they are paintings of Marie-Thérèse, yet in depicting both her, and the series of large-scale sculptures of previous months in which her features swell into generous, curving forms, they point to the fugitive nature of identity in the hands of an artist (Pictured right: Nude, Green Leaves and Bust). Ultimately Picasso’s words count for less than his work, but in navigating this exhibition with a sense of the complex transformations of identity that occur despite an apparently overwhelming biographical narrative, we would do well to remember his own comment: “I would love to paint like a blind man who pictures an arse by the way it feels.”

Lost in the seductive thrill of biography is the question of artistic identity, as it applies both to Picasso, and his muse. Because while it is deeply misleading to consider these paintings to be about – and only about – Marie-Thérèse, it is equally clear that without her, this work could not have been made. The exhibition’s great centrepiece is a room dedicated to the series of monumental nudes painted in March of 1932: proof, according to Picasso’s awestruck dealer, that painting was not dead. Ostensibly, they are paintings of Marie-Thérèse, yet in depicting both her, and the series of large-scale sculptures of previous months in which her features swell into generous, curving forms, they point to the fugitive nature of identity in the hands of an artist (Pictured right: Nude, Green Leaves and Bust). Ultimately Picasso’s words count for less than his work, but in navigating this exhibition with a sense of the complex transformations of identity that occur despite an apparently overwhelming biographical narrative, we would do well to remember his own comment: “I would love to paint like a blind man who pictures an arse by the way it feels.”

- Picasso 1932: Love Fame Tragedy at Tate Modern until 9 September

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment