DVD: Glory | reviews, news & interviews

DVD: Glory

DVD: Glory

Second film from accomplished Bulgarian directing duo adds dark comedy to repertoire

The Bulgarian co-directing duo of Kristina Grozeva and Petar Valchanov proved their skill with the scalpel in slicing through the unforgiving world depicted in their first film, The Lesson, from 2014. Their follow-up in a loosely planned trilogy, Glory continues that dissection of Bulgarian society, one now depicted on a broader canvas and with an element of pitch-black comedy that is new.

It’s a darkly entertaining watch, which involves direct comparison between two very different worlds – one that appears virtually unaffected by the social changes that followed the end of communism, the other infected with a cynicism that is very much a product of the new order that followed. Grozeva and Valchanov’s story has a pronounced simplicity that gives the film an aspect of parable.

Tsanko is treated more as an object than as a human being

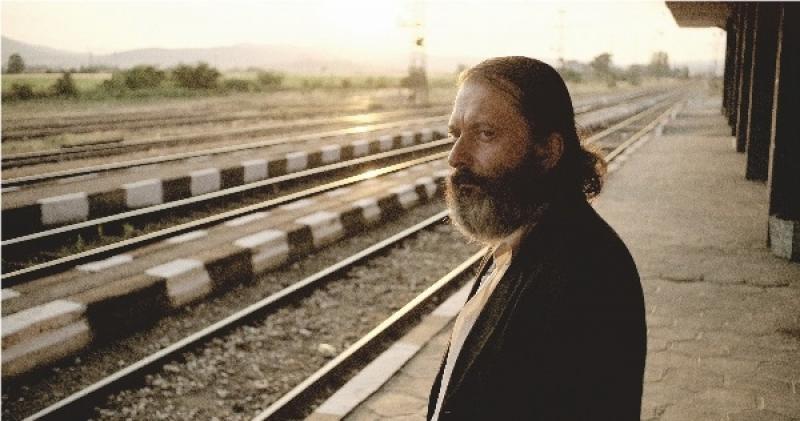

Their main character, Tsanko (Stefan Denolyubov), represents the uncorrupted old order, his thick beard and generally unkempt look making clear that he’s not concerned with appearances. He works as a linesman on the railways somewhere out in the provinces, checking the track. Something of a loner – he has a severe stammer – he’s engaged with his own private world, which revolves around domestic tasks, and keeping the exact time, something essential for his work. When one day he finds a stash of cash on the railway line, his innate honesty means he doesn’t hesitate – though he lives a very basic life indeed – to turn it in to the police. It’s a deed that sees him labelled, given the corruption of his surrounding world, a “fool of the nation”.

But it draws the attention of his bosses at the Ministry of Transport off in Sofia, for whom such a selfless gesture comes as a welcome corrective against wider corruption allegations being bandied around about the high-ups. Arch Ministry PR boss Julia Staykova (Margita Gosheva, pictured below) arranges an award ceremony that sees Tsanko brought to the capital – he’s treated throughout more as an object than as a human being – to be paraded to the press. When her distracted forgetfulness means that Tsanko loses the family watch which is a crucial part of his identity (it’s a Russian-made Slava, or "Glory" in English, historic brand), a whole destructive chain of events is set in motion, and her thoughtless (but unwitting) mistake brings drastic consequences for all. The unlucky hand of fate is a familiar element in the cinema of Eastern Europe – “inexorable” seems to be one of its recurring words – and it assumes an extra tragic element here, given the extreme innocence and naivety of one party in the story. Tsanko becomes something of a holy fool, his stammer making him excruciatingly unsuited for the cynical PR world to which he is exposed: when we witness the thoughtless laughter that he provokes there, real cruelty hits home. The directors are equally unsparing in their depiction of their heroine, however: Julia’s work concerns are played out incongruously against the background of her attempts to conceive a child through IVF, with each clinic appointment perpetually interrupted by calls on her mobile. The directors don’t need to labour their point, that she has lost track of the important things in her life: the closing chaos in which she finds herself brings that home. Even so, the darkness of the film’s implied conclusion endorses a markedly bleaker view of the world than anything that has come before.

The unlucky hand of fate is a familiar element in the cinema of Eastern Europe – “inexorable” seems to be one of its recurring words – and it assumes an extra tragic element here, given the extreme innocence and naivety of one party in the story. Tsanko becomes something of a holy fool, his stammer making him excruciatingly unsuited for the cynical PR world to which he is exposed: when we witness the thoughtless laughter that he provokes there, real cruelty hits home. The directors are equally unsparing in their depiction of their heroine, however: Julia’s work concerns are played out incongruously against the background of her attempts to conceive a child through IVF, with each clinic appointment perpetually interrupted by calls on her mobile. The directors don’t need to labour their point, that she has lost track of the important things in her life: the closing chaos in which she finds herself brings that home. Even so, the darkness of the film’s implied conclusion endorses a markedly bleaker view of the world than anything that has come before.

The satire of Glory is certainly impressive: it’s the very fluency of some of its comedy that gives rise to a more profound feeling that something is very wrong in this story told in microcosm from a wider national narrative. The gradual process of adaptation to drastic change in society is bound to be slow, and we can only hope that Grozeva and Valchanov will be around to chart it for a long time to come. The Lesson proved that they could make powerful drama out of everyday events. Glory reunites them with both that film's main cast and technical collaborators – DP work, playing heavily with handheld style, from Krum Rodriguez looks as accomplished as ever, while Margita Gosheva as Julia simply carries all before her – from their first film, but has stretched both their perspective and repertoire. Their style certainly veers towards the understated, but its power grows incrementally, and most importantly it compels an element of human involvement from us as viewers.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Glory

The Bulgarian co-directing duo of Kristina Grozeva and Petar Valchanov proved their skill with the scalpel in slicing through the unforgiving world depicted in their first film, The Lesson, from 2014. Their follow-up in a loosely planned trilogy, Glory continues that dissection of Bulgarian society, one now depicted on a broader canvas and with an element of pitch-black comedy that is new.

It’s a darkly entertaining watch, which involves direct comparison between two very different worlds – one that appears virtually unaffected by the social changes that followed the end of communism, the other infected with a cynicism that is very much a product of the new order that followed. Grozeva and Valchanov’s story has a pronounced simplicity that gives the film an aspect of parable.

Tsanko is treated more as an object than as a human being

Their main character, Tsanko (Stefan Denolyubov), represents the uncorrupted old order, his thick beard and generally unkempt look making clear that he’s not concerned with appearances. He works as a linesman on the railways somewhere out in the provinces, checking the track. Something of a loner – he has a severe stammer – he’s engaged with his own private world, which revolves around domestic tasks, and keeping the exact time, something essential for his work. When one day he finds a stash of cash on the railway line, his innate honesty means he doesn’t hesitate – though he lives a very basic life indeed – to turn it in to the police. It’s a deed that sees him labelled, given the corruption of his surrounding world, a “fool of the nation”.

But it draws the attention of his bosses at the Ministry of Transport off in Sofia, for whom such a selfless gesture comes as a welcome corrective against wider corruption allegations being bandied around about the high-ups. Arch Ministry PR boss Julia Staykova (Margita Gosheva, pictured below) arranges an award ceremony that sees Tsanko brought to the capital – he’s treated throughout more as an object than as a human being – to be paraded to the press. When her distracted forgetfulness means that Tsanko loses the family watch which is a crucial part of his identity (it’s a Russian-made Slava, or "Glory" in English, historic brand), a whole destructive chain of events is set in motion, and her thoughtless (but unwitting) mistake brings drastic consequences for all. The unlucky hand of fate is a familiar element in the cinema of Eastern Europe – “inexorable” seems to be one of its recurring words – and it assumes an extra tragic element here, given the extreme innocence and naivety of one party in the story. Tsanko becomes something of a holy fool, his stammer making him excruciatingly unsuited for the cynical PR world to which he is exposed: when we witness the thoughtless laughter that he provokes there, real cruelty hits home. The directors are equally unsparing in their depiction of their heroine, however: Julia’s work concerns are played out incongruously against the background of her attempts to conceive a child through IVF, with each clinic appointment perpetually interrupted by calls on her mobile. The directors don’t need to labour their point, that she has lost track of the important things in her life: the closing chaos in which she finds herself brings that home. Even so, the darkness of the film’s implied conclusion endorses a markedly bleaker view of the world than anything that has come before.

The unlucky hand of fate is a familiar element in the cinema of Eastern Europe – “inexorable” seems to be one of its recurring words – and it assumes an extra tragic element here, given the extreme innocence and naivety of one party in the story. Tsanko becomes something of a holy fool, his stammer making him excruciatingly unsuited for the cynical PR world to which he is exposed: when we witness the thoughtless laughter that he provokes there, real cruelty hits home. The directors are equally unsparing in their depiction of their heroine, however: Julia’s work concerns are played out incongruously against the background of her attempts to conceive a child through IVF, with each clinic appointment perpetually interrupted by calls on her mobile. The directors don’t need to labour their point, that she has lost track of the important things in her life: the closing chaos in which she finds herself brings that home. Even so, the darkness of the film’s implied conclusion endorses a markedly bleaker view of the world than anything that has come before.

The satire of Glory is certainly impressive: it’s the very fluency of some of its comedy that gives rise to a more profound feeling that something is very wrong in this story told in microcosm from a wider national narrative. The gradual process of adaptation to drastic change in society is bound to be slow, and we can only hope that Grozeva and Valchanov will be around to chart it for a long time to come. The Lesson proved that they could make powerful drama out of everyday events. Glory reunites them with both that film's main cast and technical collaborators – DP work, playing heavily with handheld style, from Krum Rodriguez looks as accomplished as ever, while Margita Gosheva as Julia simply carries all before her – from their first film, but has stretched both their perspective and repertoire. Their style certainly veers towards the understated, but its power grows incrementally, and most importantly it compels an element of human involvement from us as viewers.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Glory

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

Add comment