Russia and the Arts, National Portrait Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Russia and the Arts, National Portrait Gallery

Russia and the Arts, National Portrait Gallery

A 19th century cultural pantheon, legacy of a great patron-collector

A good half of the portraits in Russia and the Arts are of figures without whom any conception of 19th century European culture would be incomplete. A felicitous subtitle, “The Age of Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky”, provides a natural, even easy point of orientation for those approaching Russian culture, and with it the country’s history and character, without particular advance knowledge.

Much is new here, not least the artists themselves, none of whose names are anywhere near as well-known as their subjects. The wider intellectual world they inhabited may seem remote, with its conflicts between slavophiles and westernisers, those who espoused the primacy of a national element in Russian art against those who saw it as part of a wider context. This was a particularly crucial period of Russia’s historical and social development. The loose dateline given by the curators may span a convenient half-century, 1864 to 1914, but this is a 19th century show par excellence, with realism at its heart. Only a pair of late works, the little-known artist Olga Della-Vos-Kardovskaia’s portraits of Anna Akhmatova (bottom picture) and her first husband, poet Nikolai Gumilev, with their elements of Symbolism, hint at the formal experimentation which flowered with the Russian avant-garde, the style which remains much better-known outside its homeland than what we have here.

It has an intensity as bristling as some of the beards

There’s another date attached too, 1856, which chimes neatly as the year of the foundation of both Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery, which provides the 26 works here, and its present venue. “Foundation” may be a loose term, although the London museum certainly opened that year with 57 works crowded into a house in Westminster. In Russia it saw 24-year-old Pavel Tretyakov acquire his first work of art, the foundation for a collection that would grow to around 2,000 by the time he donated it to the city of Moscow in 1892; after his death six years later, it would become Russia’s main gallery of national art.

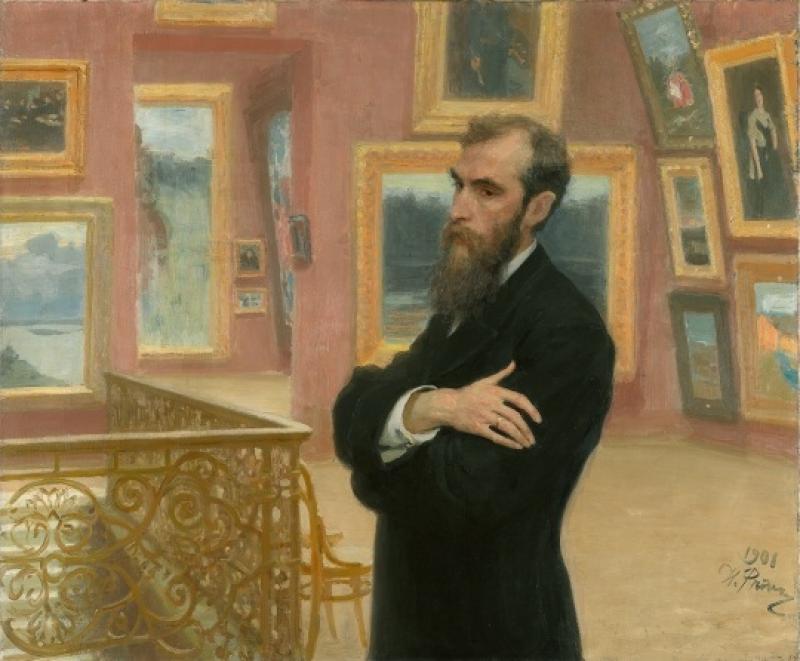

So it’s appropriate – a third “T” in the subtitle would have been deserved – that the first portrait we see is of Tretyakov himself (main picture). It’s hard to imagine a work less interested in grandstanding the achievements of its subject (though the portrait of Dostoevsky here comes close). The sense of diffidence, even introversion is strong, as Tretyakov stands alone in a hall of the gallery he has created, its walls crowded with his pictures; he looks down, avoiding engagement with the viewer, wistful, even melancholy – it's a supremely private portrait. It’s a posthumous copy from 1901 of an earlier work by Ilya Repin, who as an artist was as close to his patron and friend as any (eight works here are by Repin). Tretyakov maintained a voluminous correspondence with artists, and a phrase from one of Repin’s replies from 1870, the year after Tretyakov had placed his first portrait commission – “those whom the nation holds dear to its heart” – defines beautifully the ambitions behind Tretyakov’s nascent portrait collection.

“Writers, composers and, generally, personalities from cultural and academic circles” was how he described his priorities – had he forgotten the artists? – and literature dominates the first room. It has an intensity as bristling as some of the beards: blacks and browns dominate, half-figures against largely neutral backgrounds – no hint of extraneous decoration. The atmosphere is brooding and contemplative, whether the gaze of the subjects fixes us directly, or they’re engaged in their occupation, like Tolstoy at his writing-desk. This is Tolstoy from 1884, after the two great novels, when he was preoccupied with social issues, which concerned the artist, Nikolai Ge, equally; like many of his generation, Ge saw himself as almost a disciple of the writer.

“Writers, composers and, generally, personalities from cultural and academic circles” was how he described his priorities – had he forgotten the artists? – and literature dominates the first room. It has an intensity as bristling as some of the beards: blacks and browns dominate, half-figures against largely neutral backgrounds – no hint of extraneous decoration. The atmosphere is brooding and contemplative, whether the gaze of the subjects fixes us directly, or they’re engaged in their occupation, like Tolstoy at his writing-desk. This is Tolstoy from 1884, after the two great novels, when he was preoccupied with social issues, which concerned the artist, Nikolai Ge, equally; like many of his generation, Ge saw himself as almost a disciple of the writer.

If that pairing of subject and artist proved almost ideal, the adjacent image of Ivan Turgenev by Repin was the opposite. All went promisingly at the beginning of their sittings, but the bond had soured badly by their end, with a dismissive distance barely disguised in Turgenev’s expression. When Tretyakov didn’t think a portrait had caught the true character of its subject, he would promptly commission another: “I want a better image of him!” was his exclamation in one such case. He tried that with Turgenev – Repin himself would duly paint the émigré two more times – but in the end none proved more satisfactory than this first version from 1874, for all the friction it conveys.

There was no such need, or indeed opportunity, with Vasily Perov’s portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky (pictured above right) from two years earlier – it's the only image of the writer painted from life. There’s distance of a different kind here: the writer looks down, somehow deep into himself and his troubled life to date (he had been imprisoned and faced mock-execution); the colours are subtly muted (only Perov’s portrait of lexicographer Vladimir Dahl, depicted months before his death, seems more spectral). The company here is distinctly male: there are six women in all in the show, and the two in this first room, both actresses, are no less sombre. There’s a truly disconcerting sadness in the eyes of Pelageia Streptova, the white lace collar and cuffs edging her head and hands the only hints of light in an ocean of almost mystical darkness.

There was no such need, or indeed opportunity, with Vasily Perov’s portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky (pictured above right) from two years earlier – it's the only image of the writer painted from life. There’s distance of a different kind here: the writer looks down, somehow deep into himself and his troubled life to date (he had been imprisoned and faced mock-execution); the colours are subtly muted (only Perov’s portrait of lexicographer Vladimir Dahl, depicted months before his death, seems more spectral). The company here is distinctly male: there are six women in all in the show, and the two in this first room, both actresses, are no less sombre. There’s a truly disconcerting sadness in the eyes of Pelageia Streptova, the white lace collar and cuffs edging her head and hands the only hints of light in an ocean of almost mystical darkness.

Which makes it something of a surprise to read that Streptova made her name in the Russian provinces playing comedy and vaudeville, before she came to the empire’s two big cities where she earned fame in the plays of Alexei Pisemsky and Alexander Ostrovsky. These two hang next to their onetime star, a welcome light in their faces. Repin’s Pisemsky catches the writer at the end of his life, but there’s a droll glimmer in his eyes. Perov gives Ostrovsky’s features a deep understanding of life, but we feel they might at any moment break into a smile, even an invitation to share a glass or two. He looks squarely out at us with soft confidence; Iosif Braz’s Chekhov engages us in a similar way (pictured above left), but there’s surely more ambiguity in Chekhov’s gaze, a sense that for him the glass remains half-empty. It was the final portrait Tretyakov acquired, in the year he died: Chekhov would only live only six more and died at 44

Next come the composers, for whom national direction in culture was no less acute an issue than it was in the visual arts (the chief ideologue of the Russian school was the critic Vladimir Stasov, whose red blouse provides the only touch of colour in the first room). Nikolai Kuznetsov’s 1893 Tchaikovsky is as dark and tense as anyone here, powerful but uneasy (pictured below left). By the 1880s Tretyakov was already talking of “filling in” his portrait collection, adding subjects who remained unrepresented, and the story of Repin’s 1881 portrait of Mussorgsky has become the stuff of legend (pictured above right). Aged just 42, Mussorgsky had been hospitalised in St Petersburg for his chronic drinking, and on Tretyakov’s instruction the artist hurried there to paint him: the composer was sober, and their sittings went well, Repin catching the somehow distracted expression of a face far older than its age as well as the details, the reds of the nose and the embroidery of the shirt. Then, to mark Mussorgsky’s name-day, a nurse smuggled in a bottle of cognac: when Repin returned the following day for a final session, his subject was dead.

Next come the composers, for whom national direction in culture was no less acute an issue than it was in the visual arts (the chief ideologue of the Russian school was the critic Vladimir Stasov, whose red blouse provides the only touch of colour in the first room). Nikolai Kuznetsov’s 1893 Tchaikovsky is as dark and tense as anyone here, powerful but uneasy (pictured below left). By the 1880s Tretyakov was already talking of “filling in” his portrait collection, adding subjects who remained unrepresented, and the story of Repin’s 1881 portrait of Mussorgsky has become the stuff of legend (pictured above right). Aged just 42, Mussorgsky had been hospitalised in St Petersburg for his chronic drinking, and on Tretyakov’s instruction the artist hurried there to paint him: the composer was sober, and their sittings went well, Repin catching the somehow distracted expression of a face far older than its age as well as the details, the reds of the nose and the embroidery of the shirt. Then, to mark Mussorgsky’s name-day, a nurse smuggled in a bottle of cognac: when Repin returned the following day for a final session, his subject was dead.

The concentration of these works appears all the more remarkable given that portraiture in Russia was barely a century old when they were being created. The stiff images of nobility that preceded them had nothing approaching the psychological depth that impresses here. If the show’s tight arrangement is dictated by its two rooms, the paintings are also hung appreciably lower than at their Moscow home, making the face-to-face intensity, the close-up brushstroke texture all the more immediate. For Russian visitors it will be a new experience to see the portraits together in a single space: they may have been the early priority for Tretyakov, but his horizons soon expanded to include Russian art in its entirety, and from the 1880s the portraits were divided, with galleries rearranged by artist, as they remain today.

Simultaneously, the distinction between an eminent subject specially selected for this gallery of notables, and portraits that had their principal value as works by an eminent artist, gradually became blurred. Repin’s elegant full-length Baroness Varvara Ikskul von Hildenbandt depicts the aristocratic hostess of a Petersburg salon, but it’s a moot point whether subject or artist has brought it here. It hangs next to portraits by Mikhail Vrubel and Valentin Serov, each of the artist's wife, which introduce a refreshing sense of light and plein air space. Though the other work here by the neurasthenic Vrubel is a disconcertingly fractured, neurotically dark portrait of Savva Mamontov, another great industrialist-patron of the arts.

Simultaneously, the distinction between an eminent subject specially selected for this gallery of notables, and portraits that had their principal value as works by an eminent artist, gradually became blurred. Repin’s elegant full-length Baroness Varvara Ikskul von Hildenbandt depicts the aristocratic hostess of a Petersburg salon, but it’s a moot point whether subject or artist has brought it here. It hangs next to portraits by Mikhail Vrubel and Valentin Serov, each of the artist's wife, which introduce a refreshing sense of light and plein air space. Though the other work here by the neurasthenic Vrubel is a disconcertingly fractured, neurotically dark portrait of Savva Mamontov, another great industrialist-patron of the arts.

That phenomenon of patronage provides the show’s final theme: its final work is Valentin Serov’s Ivan Morozov. A generation younger than Tretyakov, Morozov began collecting Russian art like his predecessor, then at the beginning of the 20th century turned his attention to modern French painting instead. Serov’s 1910 portrait depicts him against the background of Cézanne’s Fruit and Bronze, which Morozov had acquired that year. Russian collectors, who proved among the first to recognise Matisse and Picasso, were again distinguishing themselves, albeit in a different direction from that of Tretyakov.

It was an engagement with the acquisition of art that surely matches any of the great collectors of history. The Russian artists of Tretyakov’s period were eager for their works to enter his collection: it was a new phenomenon, intended not least for the public (even before he presented everything to his native city, the Tretyakov home was open to visitors). Assembling a portrait gallery of “the best of the people” was intended for the people, conceiving and defining a new sense of national identity through that very 19th century concept of its great individuals.

It was an engagement with the acquisition of art that surely matches any of the great collectors of history. The Russian artists of Tretyakov’s period were eager for their works to enter his collection: it was a new phenomenon, intended not least for the public (even before he presented everything to his native city, the Tretyakov home was open to visitors). Assembling a portrait gallery of “the best of the people” was intended for the people, conceiving and defining a new sense of national identity through that very 19th century concept of its great individuals.

The parallels with the National Portrait Gallery are fascinating, however different the process must have been in 1856 in England, where Thomas Carlyle and others had led a public movement that received support from parliament, to that in Russia, where a single Moscow merchant embarked on his private initiative. The happy 160th anniversary coincidence will see a reciprocal show of British portraiture, “From Elizabeth to Victoria”, from the National Portrait Gallery opening at the Tretyakov next month. This major cultural exchange has been five years in the making, its progress apparently never once threatened by the perilously fluctuating state of relations between Russia and Britain. A happy thought, indeed.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment