Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans | reviews, news & interviews

Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans

Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans

The movie star who dreamed of being a race ace

By the end of the 1960s, Steve McQueen was at the top of the Hollywood heap. Star turns in The Great Escape, The Thomas Crown Affair and Bullitt had established him as the King of Cool, a self-contained anti-hero whose minimalist, watchful performances radiated a mysterious sex appeal.

But, as this haunting documentary by Gabriel Clarke and John McKenna explains, the instinctively rebellious McQueen had a burning desire to throw off the shackles of the big studios. Thus he formed his own production company, Solar Productions, and, funded by a deal with Cinema Center Films, set out to make his motor racing film Le Mans.

If speed-freak McQueen hadn't succeeded in movies he might well have a made a living as a driver, and in 1970 he partnered future Formula One driver Peter Revson in the 12 Hours of Sebring sports car race, finishing second. Now he zeroed in on the big daddy of all sports car events, the 24 Hours of Le Mans, aiming to use it as the basis of a story in which he would break what he termed the "film barrier". All the driving sequences would be shot at true racing speeds of up to 240mph, using real footage from the 1970 Le Mans race intercut with specially shot sequences using professional drivers, as well as McQueen himself. As Gabriel Clarke puts it, "McQueen didn't want slo-mo, he didn't want any use of special effects, he wanted the real cars going at the real speeds. That was the benchmark." He also wanted to surpass John Frankenheimer's Grand Prix, in which McQueen had been pipped to the lead role by James Garner.

Hours of Le Mans, aiming to use it as the basis of a story in which he would break what he termed the "film barrier". All the driving sequences would be shot at true racing speeds of up to 240mph, using real footage from the 1970 Le Mans race intercut with specially shot sequences using professional drivers, as well as McQueen himself. As Gabriel Clarke puts it, "McQueen didn't want slo-mo, he didn't want any use of special effects, he wanted the real cars going at the real speeds. That was the benchmark." He also wanted to surpass John Frankenheimer's Grand Prix, in which McQueen had been pipped to the lead role by James Garner.

With John Sturges, who'd worked with McQueen on The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape, installed as director, the project looked like box-office gold dust, but it never got fully into gear. As producer, McQueen could overrule his director, and Sturges grew increasingly exasperated by the star's interference and changes of mind. A relay of writers worked on the screenplay, but McQueen was so obsessed with achieving some imaginary ideal that he could never decide exactly what he wanted.

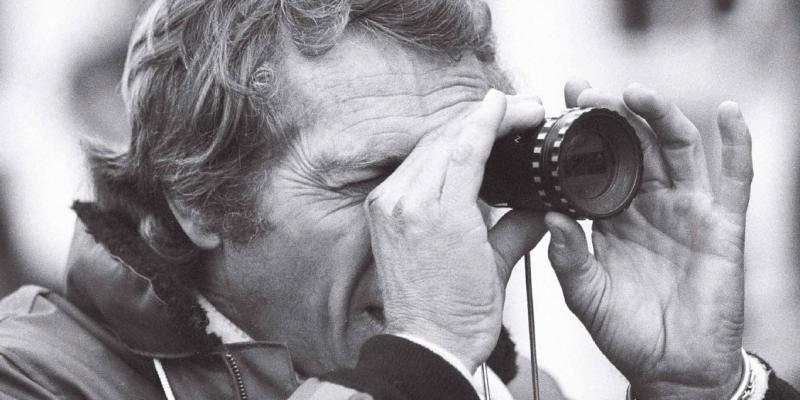

The racing footage was indeed spectacular, and Clarke and McKenna have unearthed a priceless hoard of unused movie footage as well as some excellent home movie material which gives intimate glimpses behind the scenes. In Le Mans itself, however, character development wasn't on the menu and, beyond McQueen's character Michael Delaney in his Porsche 917 battling the Ferrari 512 of German driver Erich Stahler (Siegfried Rauch), nor was plot. Eventually the movie was completed by unknown director Lee Katzin, and bombed commercially (McQueen, demoted from producer to mere actor, didn't attend the premiere). He went on to star in a string of blockbusters, but his dream of creating his own movie empire was dead. (McQueen entertains friends at Le Mans, below.)

But even if you hate motor racing, The Man & Le Mans offers illuminating insights into McQueen's life and career. McQueen's son Chad, whose own motor racing aspirations were wrecked by a gruesome accident at Daytona, recalls his excitement at being at Le Mans with his dad as a child, while the star's ex-wife Neile supplies some rose-tinted reflections on her life with him, though they divorced in 1972. The fact that McQueen would "entertain" up to a dozen women a week while he was making Le Mans probably had something to do with it. It had been an assignation with an unknown woman which led to McQueen missing the party at Sharon Tate's Los Angeles house in August 1969 which ended in mass slaughter by Charles Manson and his gang. Thenceforth, he regularly kept a gun handy.

But even if you hate motor racing, The Man & Le Mans offers illuminating insights into McQueen's life and career. McQueen's son Chad, whose own motor racing aspirations were wrecked by a gruesome accident at Daytona, recalls his excitement at being at Le Mans with his dad as a child, while the star's ex-wife Neile supplies some rose-tinted reflections on her life with him, though they divorced in 1972. The fact that McQueen would "entertain" up to a dozen women a week while he was making Le Mans probably had something to do with it. It had been an assignation with an unknown woman which led to McQueen missing the party at Sharon Tate's Los Angeles house in August 1969 which ended in mass slaughter by Charles Manson and his gang. Thenceforth, he regularly kept a gun handy.

With the aid of some melancholy ambient music, the film assembles a picture of a man from a broken home driven by a ferocious desire to fight his way to the top – "I come from the gutter and I'm not a compromiser" – but whose reach ultimately exceeded his grasp. His ambivalence about his success is revealed in an audio interview where he complains that while he loves acting, "being a movie star is a pain in the ass", yet at the same time he revelled in the power that his stardom gave him. The last we hear from him is over the closing credits, in a faint, distant interview given while he was dying from lung cancer in 1980. "In my life my daydreams came true," he says. "It's just that I've run out of gas."

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Add comment