The King of Marvin Gardens | reviews, news & interviews

The King of Marvin Gardens

The King of Marvin Gardens

Melancholy meets irrational optimism in Bob Rafelson's New Hollywood classic

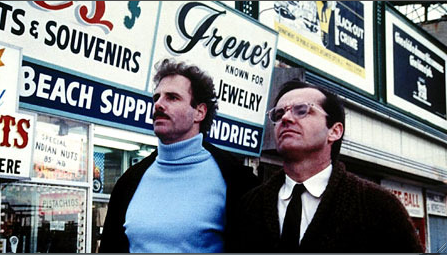

Bob Rafelson’s 1972 The King of Marvin Gardens takes its title from the Atlantic City Monopoly property, connoting the New Jersey resort’s then imminent future as a board game for real-estate developers. The conman Jason Staebler (Bruce Dern) acknowledges its status thus when his younger brother David (Jack Nicholson) arrives in town to bail him out of jail.

Jason also imports David to persuade him to join in his fantastical scheme of acquiring and running a casino on an island north of Hawaii. David isn’t expected to invest in the deal, only to enjoy its fruits: the corrupt, cynical world of Rafelson’s movie, peopled with black mobsters and Runyonesque chancers and shot by László Kovács in a bleakly autumnal A.C., can’t be described as loveless.

Not for nothing has 'Marvin Gardens' been likened to 'Waiting for Godot'A keystone of the 1970 American New Wave, or New Hollywood, Marvin Gardens was the last fictional film made by the independent production outfit that started as Raybert and morphed into BBS (for “Bob” and his partners Bert Schneider and Steve Blauner). No less than Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show (1971), the film that preceded it on the company’s roster, it is a movie about things coming to an end, or being exposed as a sham: a relationship between a controlling worryguts and his brother the reckless dreamer, who seldom meet yet are weirdly codependent (a metaphor for Rafelson and Schneider?); the love affair between the dreamer, raffish and virile, and a “middle-aged kewpie doll”; the pre-gambling Atlantic City of Tower of Babel hotels that, in a few years, will make way for casinos; not least the American Dream (Dern and Nicholson, pictured below).

Whereas Bogdanovich’s film is a Fordian elegy, Marvin Gardens is a ballet of futility. There's an Altman-like irony in its comic set pieces, as when Sally (Ellen Burstyn) welcomes David from Philadelphia by bringing a shambolic band onto the station platform; when Jason and David huckster a group of old women in a Boardwalk store; when they spoof the Miss America Pageant, with David as host, Sally as organist, and her ward Jessica (Julia Anne Robinson) as the sole entrant and winner, in the empty AC Convention Hall. Mostly, the quartet hangs around fencing and bickering as they anticipate the day when the funding of Jason’s casino will whisk them off to Paradise. Not for nothing has Rafelson’s followup to Five Easy Pieces (1970) – his, Nicholson's, and BBS’s study of an irresponsible man’s existential crisis – been likened to Waiting for Godot.

Foregrounding one dysfunctional family, Marvin Gardens draws on the implied demise of another. Jason and Sally (parents) and David and Jessica (children) make up the first clan, which is riddled with incest. The other is Jason and David’s original family, unseen and seemingly extinct, except for the brothers themselves and the grandfather who lives with David in Philadelphia.

Foregrounding one dysfunctional family, Marvin Gardens draws on the implied demise of another. Jason and Sally (parents) and David and Jessica (children) make up the first clan, which is riddled with incest. The other is Jason and David’s original family, unseen and seemingly extinct, except for the brothers themselves and the grandfather who lives with David in Philadelphia.

Once, as shown in a home movie watched by the old man at the end, Jason and David were two boys playing happily on a beach. What befell them that turned flamboyant Jason into a felon with delusions of grandeur and David into an introverted terminal depressive who only perks up as a late-night radio raconteur of tragicomic shaggy-dog reminiscences? Why do they both tell themselves and anyone who’ll listen futile tales about incidents that never happened, or dreams that never will?

Rafelson and Jacob Brackman’s script never divulges the backstory, though there are dabs of past anguish: as a boy, David would tell Jason, two years older than him, “You’re not the boss of me.” Jason has spent at least two “grim” months in prison; David’s equivalent is a stay in a rest home, or “loony bin” as Jason puts it. David’s opening on-air monologue, which has the quality of a confession made to a shrink, comprises the apocryphal story of how they allowed the grandfather to choke to death on a fish bone, but it discloses the more important detail that David believes “at that moment my brother and I became accomplices forever.” If grandfather is still hale, what event bound the brothers in shame and need? That Rafelson and Brackman never uncover this anti-Rosebud deepens the mystery.

The two women are no less damned by the past. Sally, who gives the impression of being a veteran of 50 failed romances, inherited Jessica as a stepdaughter who has known her “most of my life”, after her father jumped ship. She has taken Jessica whoring with her too, “as part of the package.” “There have been lots of men,” the waif warns off David when he naively hints there’s something between them. She has become the “meal ticket” for Jason and Sally, who masochistically buries her cosmetics in the sand and cuts her hair short after she learns that Jessica has supplanted her in Jason’s affections. Their rivalry, unnoticed by the heedless Jessica, is what they contribute to the party as the story switchblades into tragedy.

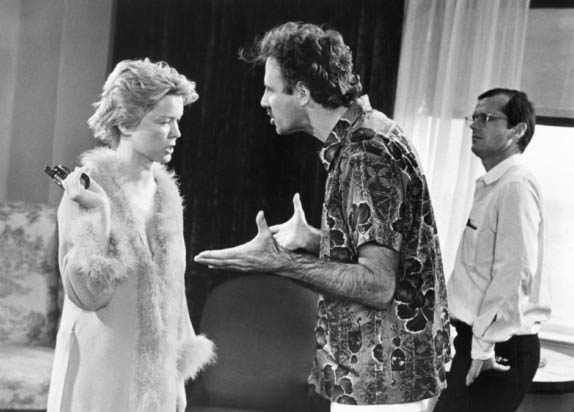

Marvin Gardens throbs with sociopolitical observations about property, capitalism, crime, America in the age of Nixon, civic decay, cultural shifts, and even race relations. Yet it’s as a psychologically realistic portrait of outsiders – a BBS trope – that it resonates today. Rafelson’s masterstroke was to cast his leading men against type – Nicholson was originally to have played Jason and Dern was to have played David. The result was that Dern supplied the film with charm and ebullience, leaving Nicholson to fret and fuss in David's neurotic stew. Burstyn, who played the Cybill Shepherd character's tough, bitter mother in The Last Picture Show, shows Sally’s bounce and humour curdling into self-pity, but she doesn’t telegraph the last emotion she displays (Burstyn pictured above with Dern and Nicholson).

Marvin Gardens throbs with sociopolitical observations about property, capitalism, crime, America in the age of Nixon, civic decay, cultural shifts, and even race relations. Yet it’s as a psychologically realistic portrait of outsiders – a BBS trope – that it resonates today. Rafelson’s masterstroke was to cast his leading men against type – Nicholson was originally to have played Jason and Dern was to have played David. The result was that Dern supplied the film with charm and ebullience, leaving Nicholson to fret and fuss in David's neurotic stew. Burstyn, who played the Cybill Shepherd character's tough, bitter mother in The Last Picture Show, shows Sally’s bounce and humour curdling into self-pity, but she doesn’t telegraph the last emotion she displays (Burstyn pictured above with Dern and Nicholson).

Robinson had been part of the ensemble of Henry Jaglom’s BBS film A Safe Place (1971). Marvin Gardens, which she appeared in when she was 20, was her only other film. Rafelson felt let down by her performance – or was that because he allegedly failed in his pursuit of her? She makes Jessica alarming – a blithe hippie who, fragile in some shots, oozes seediness as she patronizes David’s sexual shyness. And, starting small and finishing big as she tapdances languidly toward the camera in the faux beauty pageant, she nails the movie’s satire of the success ethic. She had a drug problem and may not have been ambitious, but she was talented. Sadly she died in a fire in Oregon in April 1975.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Add comment