theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Martin Carthy | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Martin Carthy

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Martin Carthy

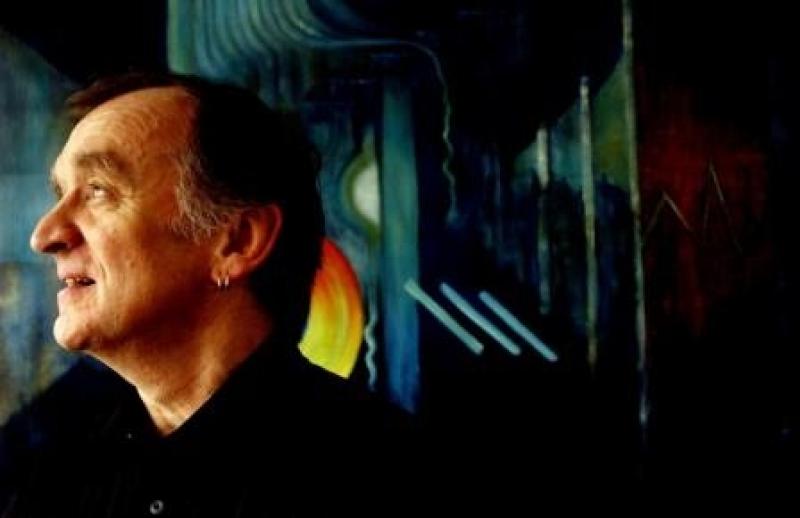

At 70, the influential folk musician contemplates a privileged existence

One of Britain’s most esteemed and influential folk artists, Martin Carthy (b 1941) celebrates his 70th birthday on 21 May. The occasion is being marked by the release of a two-disc career overview, Martin Carthy Essential, and next weekend's celebratory concert at the Southbank Centre, London.

A man whose favourite phrase appears to be “we had a fabulous time", Carthy has been a pivotal figure on the folk scene for almost half a century. He found his feet in the folk revival of the late 1950s and later met and directly influenced future rock icons such as Paul Simon and Bob Dylan when they busked into London in the early 1960s. He also provided a guiding light for British contemporaries such as Donovan and Richard Thompson.

It's not hard to hear why. Carthy is a wonderfully direct, uncomplicated singer and his guitar-playing is solidly percussive yet supremely melodic. Always serving the song rather than his ego, when he sings and plays it is without an ounce of affectation or glamour, allowing the deep emotion and narrative twists and turns of Britain’s traditional songs to ring out clear and true.

It's not hard to hear why. Carthy is a wonderfully direct, uncomplicated singer and his guitar-playing is solidly percussive yet supremely melodic. Always serving the song rather than his ego, when he sings and plays it is without an ounce of affectation or glamour, allowing the deep emotion and narrative twists and turns of Britain’s traditional songs to ring out clear and true.

He has forged a deserved reputation as both an adventurous solo artist and a happily promiscuous collaborator. As well as numerous solo albums and gigs, there have been spells playing and recording with The Albion Band, pioneering folk-rock group Steeleye Span, Brass Monkey and, most regularly, the legendary Fairport Convention fiddler Dave Swarbrick.

His career is entwined with the life of his family. His wife of almost 40 years, Norma Waterson, is a member of one of British folk music’s most significant dynasties, The Watersons, which Carthy joined in the 1970s. Their daughter, Eliza Carthy, enjoys a highly successful career in her own right. He has worked frequently with them both, most recently in Waterson:Carthy. Norma has been seriously ill since late 2010 but her condition is now showing some signs of improvement.

In 1998 Carthy was awarded an MBE in acknowledgement of his colossal contribution to British folk music and in 2002 was given an honorary doctorate in music from Sheffield University. "Fabulous," he says happily, although I suspect a crisply rendered version of "Prince Heathen" would bring him just as much satisfaction.

GRAEME THOMSON: Could you describe the environment you grew up in and what part music played in it?

MARTIN CARTHY: There was bombing going on in May 1941 and the hospital was evacuated to a place called Lemsford, near Hatfield. I was born there but I lived in and around Hampstead: Primrose Gardens, near Primrose Hill, and Aberdare Gardens - which was very unsuccessful because my dad tried to go upscale a bit and came unstuck - and then Constantine Road by Parliament Hill. It was a great life. We always loved singing in the family. I had a few piano lessons but I was very unsuccessful so that stopped. It was always singing, really. I was a chorister when I was about 12 at the Queen’s Chapel of the Savoy. Our school, St Olive’s and St Saviour’s Grammar School for Boys, right by Tower Bridge at that time, supplied the choristers to Southwark Cathedral and the Queen's Chapel of the Savoy.

You must have been good. I guess they didn’t let in just anyone?

I was all right, actually. Very much all balls and no forehead. I would try and sing at the top of my voice so I was always coming unstuck – that lasted into adulthood! The music was gorgeous: Thomas Tompkins, Thomas Tallis, Orlando Gibbons, with a little bit of Vaughan Williams thrown in. I loved Orlando Gibbons, but by the time I was 15 it was all skiffle. Skiffle everywhere. I became intrigued when somebody said to me that “Gamblin’ Man” was originally an Irish song.

I was even more intrigued when a friend who was in the year above told me about this pub in Holborn called The Princess Louise where they sang the original versions of all the skiffle hits. I decided I was going to go along there, it sounded really exotic and out of the way and unusual, and I was always attracted by that. It was Ewan MacColl and Bert Lloyd’s club, The Ballads and Blues, and the guy who told me about it was the best friend of Bert Lloyd’s son, Joe Lloyd, who had the best skiffle group in the school. In fact, one of the things I said to him was, "Where do you get your songs from?" He said, “My dad.” And that was Bert Lloyd, although I didn’t get to hear him sing until much later. There ain’t no such thing as coincidence, I truly believe that.

Did that club become a kind of Mecca for you?

Yeah, I started going along to The Ballads and Blues wherever it was, because it started moving around all over the place. I didn’t go every week but I kept my ear to the ground – there was MacColl and Lloyd, but there was also Fitzroy Coleman, a wonderful, wonderful West Indian jazz guitar player who accompanied Ewan and also sang and wrote calypso. They were brilliant songs, and then he would play this extraordinarily intricate jazz guitar. Very beautiful. There were often a lot of visiting Americans, including a man called Ralph Rinzler, who was a mandolin player. He later became the head of folk culture at the Smithsonian Institute. The next time I heard of him he was in The Greenbriar Boys, a Boston bluegrass band. Peggy Seeger was there as well, of course. I was fascinated by all these people.

Watch footage of Fitzroy Coleman

Ewan MacColl gets quite a bad press these days as folk’s didactic, humourless gatekeeper...

Ewan had a rule which has annoyed people over the years because they have chosen to misinterpret it. He loved the idea of people playing American music, but he wanted Americans to do it. He wanted English people to find out what they had in store, Scots people to do the same, and it was a case of, “This is my club, and that’s the rule I make.” I don’t have any problem with that. If you wanted to sing other stuff, you'd go somewhere else. And later on in his life he acknowledged that some of those people who indeed did go somewhere else could play a bit. He was not completely blind and deaf.

When did it occur to you that this was something you wanted to do - and could do?

Well, I always loved it, I always wanted to play. I heard Big Bill Broonzy when I was about 16. We didn’t have a record player at home, we had an old wind-up gram that only played 78s, so I’d go round to my mate's house and hear Big Bill Broonzy records and slow them down and try and play like that. That was the way I learned guitar.

Elizabeth Cotton wrote a song which was a huge skiffle hit in this country for Chas McDevitt, called “Freight Train”. I went to Dobell's jazz record shop in Charing Cross Road – they had one bin on the counter that had folk records in - and I saw this record by Elizabeth Cotton called Negro Folk Songs and Tunes, on Folkways, and the second track was “Freight Train”. I played it on my friend’s record player and just slowed it down and learned how to do it. All the music I played on the guitar when I first started to play properly was American, but I wanted to sing English songs so it was a case of just trying to apply a different set of rules but using that style as a foundation.

Elizabeth Cotton wrote a song which was a huge skiffle hit in this country for Chas McDevitt, called “Freight Train”. I went to Dobell's jazz record shop in Charing Cross Road – they had one bin on the counter that had folk records in - and I saw this record by Elizabeth Cotton called Negro Folk Songs and Tunes, on Folkways, and the second track was “Freight Train”. I played it on my friend’s record player and just slowed it down and learned how to do it. All the music I played on the guitar when I first started to play properly was American, but I wanted to sing English songs so it was a case of just trying to apply a different set of rules but using that style as a foundation.

You were involved in theatre at one point early on. Was that a serious career choice?

When I left school I decided I was going to be an actor. I’d been in the school play which obviously meant I was a really good actor! It didn’t take long for theatre and I to come to an agreement that I was, in fact, rubbish. But I had a great time for 18 months. My first job was prompter at Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre, I had a fabulous time, and then I did a nine-month tour on the number-one circuit as an ASM in The Merry Widow. That was fabulous, because we were just coming to the end of variety and you were seeing how theatre was changing. There were all these different people working on that show: people like Vanessa Lee, from light opera, who was Irving Berlin’s great discovery, alongside a cancan troupe called Marie De Vere’s Ballet Montmartre, who all came from Sheffield, Chesterfield and Hackney. A fabulous bunch of girls, really down to earth, and by God did they work hard.

Then I did a summer season in Theatre-in-the-Round in Scarborough, and after that I was out of work. By that time I knew that theatre was something I was not going to be successful at. It was a mutual agreement!

I had a guitar and I had a repertoire and I would go and sing in coffee bars and play in folk clubs when I could. There weren’t that many around at the time. My repertoire was one of those around-the-world-on-the-magic-carpet-of-my-guitar jobs, but gradually it started focusing on English stuff, or British Isles stuff. I started travelling to the few folk clubs there were, and meeting other people who were doing the same thing, like Louis Killen. I just learned and learned and learned and learned.

I started digging around the Vaughan Williams library in Cecil Sharp House and found all sorts of extraordinary stuff there on manuscript and cassette, and now on CD, which intrigued me then and which now I love with a passion. My favourite thing is to listen to some of those recordings that were made around 1908. Just people singing. They sing quite beautifully, they don’t obey the rules, they are doing it their way and it’s quite, quite glorious.

Has that unstudied quality always been attractive to you? (Martin Carthy pictured right: photo Doc Rowe)

Has that unstudied quality always been attractive to you? (Martin Carthy pictured right: photo Doc Rowe)

Yeah. It’s deceptive. Sometimes it’s very straightforward, and carried by the passion of the thing, and other times it’s highly sophisticated. Some of the melodies and rhythms – the pulses of these things – are extraordinarily sophisticated. People don’t necessarily sing metronomically, and when they don’t there are some fabulous results.

Do you get transported when you sing or are you just intent on telling the story?

You do get transported sometimes, and it’s singing in front of an audience that does it because they will transport you as well. The workload is even. This stuff works best, or much better, in smaller places where you can reach out and touch the audience. That’s when things really start to happen, that’s the connection. That’s important with this stuff. It adapts quite beautifully to those circumstances. It doesn’t really work in arenas, I don’t think.

During the folk scene in the early 1960s people like Bob Dylan and Paul Simon started coming through London; you met and influenced them. Did you instantly recognise it as an extraordinary time, or did its significance only become clear in hindsight?

This will give you a clue to my thinking, and I think our collective thinking, back then. There used to be a folk magazine called John Bull which went bust and was replaced by another magazine, I can't for the life of me remember its name. When Bob came over in 1964 for that concert at the Festival Hall, which was a fabulous concert, there was an article in this magazine all about him, and the heading was: "Is This the Hit Parade of Tomorrow?" We read it and were on the floor with laughter: “Don’t be silly!” Well, how happily were we eating our words just one year later when “The Times They are a-Changin'” was in the charts because John Lennon had given his seal of approval. Bob came over in 1965 and 1966 and he was huge. It was extraordinary. It was out of the question that anything Bob was doing would get anywhere near Ready Steady Go, and yet it happened.

Were you in any sense ambivalent about that?

No, I didn’t have any problem with it at all. I remember going to see him at the Festival Hall and the thing that is absolutely etched into my mind is when he sang “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”. He finished that song and the place exploded. It. Fucking. Exploded. That was when I realised – putting it tritely – the power of the narrative song. I've always felt that that was exactly what some of those older traditional narrative ballads could do. They don’t have that quite brilliant surprise of being current, but they have that power.

In 1965 you released your debut album, Martin Carthy (pictured below). Was that of paramount importance to you then, or was it simply an adjunct to the vital business of playing live?

It was a big deal at the time because the major labels hadn’t taken any notice of folk music, and suddenly there was a folk boom. A friend of mine called it "The Great Folk Scare!" It was a feather in my cap to have a contract with Fontana, it was a big deal, and by the time that had sunk in I was doing the second album with Dave Swarbrick. We had a fabulous time. It gave us a big leg-up, we were quite important because we had a record deal.

On reflection I became very glad when everybody could do it. Bill Leader, who had been an engineer at Topic, started his own label Trailer. He just started recording people on the folk scene, because he said the important thing is that this music is changing and it needs documenting. He would make the records, hand them to the artists and they would go and sell them on gigs. This hadn’t been done before. It became more and more DIY, and I was very happy about that. I didn’t like all the stuff that was coming out but then do you ever?

On reflection I became very glad when everybody could do it. Bill Leader, who had been an engineer at Topic, started his own label Trailer. He just started recording people on the folk scene, because he said the important thing is that this music is changing and it needs documenting. He would make the records, hand them to the artists and they would go and sell them on gigs. This hadn’t been done before. It became more and more DIY, and I was very happy about that. I didn’t like all the stuff that was coming out but then do you ever?

In the late 1960s you joined Steeleye Span, who married traditional folk music with electric instrumentation. How much resistance was there to that idea at the time?

You’d be surprised at how little there was. We did the university circuit a lot – not the uni folk clubs, we did the rock'n'roll halls. If you’re playing electric you need that space, you could open up a bit and then it got interesting. I learned a lot from it. I learned economy.

Really? I’d have thought it might have been the reverse...

Well, I’ve never been one of those guitar players. I’ve always been an accompanist. So yes, it taught me economy.

When did The Watersons first show up on your radar?

Well, I first met Norma back in 1961 and we fell in love at first sight, but she was married and I wasn’t. The next time we met I was married and she wasn’t. We were very good about those sorts of things. Then she went away to Montserrat to be a DJ, and when she came back in Christmas 1971 I stalked her!

You can’t say that....

Ha! We made this album called Bright Phoebus. I’d stayed with her a couple of times and I'd heard Lal [Waterson’s] songs, which I was absolutely thunderstruck by. I told Ashley Hutchings about it, and Ashley is a doer, an organiser. He called Bill Leader and asked if he wanted an album of Lal’s songs, and Bill was delighted. So Ashley lassoed most of Fairport Convention: the band was Ashley, Richard [Thompson], me and Dave Mattacks, although everybody and his grandma came in and sang in the end, including one lad who had just come in to deliver a package. He never got paid, poor sod. The album took a week to make. After that I went back to London, then went up to the Cleethorpes Festival where I’d arranged to meet Norma. I walked in the door and said, “I was thinking. If I said to you should we get married, what you would say?” A bit roundabout. She said, “Well, I would say yes.” That was the end of May 1972, and we got married three weeks later.  How did The Watersons (pictured right, with Carthy on the far left and Norma next to him) influence you?

How did The Watersons (pictured right, with Carthy on the far left and Norma next to him) influence you?

They were the people who changed everything when they came on the scene in the 1960s. Before that the groups were all modelled on The Weavers: a guitar player, a banjo player and a girl singer – no matter what else there was, those things were always there. And The Watersons changed all that. They became two blokes and two lassies singing in that extraordinary harmony and occasionally unison. When I joined it was a question of slotting into that.

You’ve slotted into a lot of units: Steeleye Span, The Watersons, Waterson:Carthy, The Albion Band, Brass Monkey. How easy is it to do that and also retain a clear sense of your own identity?

It’s about understanding that you’re going to be making a contribution, so just relax. It will happen. Relax. You’ve been invited to join, calm down and see the lie of the land.

Watch Waterson:Carthy performing "Raggle Taggle Gypsies"

It doesn’t appear that you have ever had an overwhelming urge to write your own songs.

I’ve written occasionally. Done a lot of rewriting, and reworking especially, and occasionally reconstructing. The first song I was really driven to write was about the Falklands War, called “Company Policy”. One of the things about my introduction to the folk scene was that it was nearly always politically driven. We would go on demonstrations and play concerts for CND and the anti-apartheid movement and stuff like that. There was always this political dimension.

I was with The Watersons and we were at this folk festival in Telford. There was a street-theatre group there called the Fabulous Salami Brothers who were great. Lots of comedy, but there was always a tougher aspect to what they did. One of them stood up and sang a song called “Ghost Story”, about a soldier who had died in the Falklands coming back to haunt Margaret Thatcher. Well, a section of the audience booed him, and our lot were shouting back. I was utterly, utterly enraged that any real awareness had obviously evaporated during the 1970s, when we all got a bit fat and lazy I’m very much afraid. I went home and started trying to write this song. It took forever. I remember thinking I’d finished it and sang it to this woman whose judgment I really trusted. I said, “What do you think?” She said, “I think the bit you like best is the bit I like least.” Oh! I went home and dismantled the song and rewrote it, and I’m glad I did, because it was a decent song in the end and I still sing it occasionally.  Two-thirds of the way through that rewrite another song appeared, called “A Question of Sport”. That was tougher to write. It was about South Africa just before the release of Mandela. Three verses came out – wham – in one go. I’d been reading Kurt Vonnegut, where everything comes out at a slightly skewed angle, and those three verses had, I think, that kind of feel about them. Almost dismissive. But the song got terribly earnest near the end. Oh Christ, fuck, it took forever to just relax and get the rest of it to flow like that. I think it’s OK in the end, but I tell you what, I acquired a massive respect for songwriters who seem to be able to knock them out. I’ve seen Liza do it. We’ve been out on the road as Waterson:Carthy and she’ll suddenly disappear: “I’ve just got to nip out to the car and write this song down.” And she’ll finish it, damn near. The whole idea is cooking up in her head and she gets it down on paper quickly. I’m full of admiration for that. Whereas occasionally I get out the crowbar...

Two-thirds of the way through that rewrite another song appeared, called “A Question of Sport”. That was tougher to write. It was about South Africa just before the release of Mandela. Three verses came out – wham – in one go. I’d been reading Kurt Vonnegut, where everything comes out at a slightly skewed angle, and those three verses had, I think, that kind of feel about them. Almost dismissive. But the song got terribly earnest near the end. Oh Christ, fuck, it took forever to just relax and get the rest of it to flow like that. I think it’s OK in the end, but I tell you what, I acquired a massive respect for songwriters who seem to be able to knock them out. I’ve seen Liza do it. We’ve been out on the road as Waterson:Carthy and she’ll suddenly disappear: “I’ve just got to nip out to the car and write this song down.” And she’ll finish it, damn near. The whole idea is cooking up in her head and she gets it down on paper quickly. I’m full of admiration for that. Whereas occasionally I get out the crowbar...

The Essential album is a pretty comprehensive career overview. How hard was it to a) listen back to your own work and b) select the tracks?

I had nothing to do with it. The only thing I asked when I was told it was happening was that they put on one track that I wanted, which was “The Maid of Australia”. I love that song. I just think occasionally something magic happens in a studio. While John [Kirkpatrick] and I were doing it something happened and I wanted to mark that down. Other than that it was preesented to me as a fait accompli. They told me what they were going to do, I asked for that track, then they showed me and said, “Do you approve?” I didn’t see anything there to object to, although there’s stuff there I don’t like.

Why?

There was a period in my life when I thought I sang like a complete berk, but I’m afraid it’s history. It was in the 1970s. I was playing and singing in a very brittle way, and I just had to try and shake it off. It’s quite hard to do.

Were you aware at the time that you were doing that?

I became aware after a while that I was making this ridiculous noise, so I decided to try and change everything. I became obsessed with style, actually. Silly. I imagined that there is such a thing as an English style and of course there isn’t, it’s nonsense. An English style is made up of just about every singer you’ve ever heard, like a big patchwork. That’s the exciting part of it. You can listen to a person sing and listen to them speak and match them up. With old singers you can do that.

Is that how you define good singing?

Yes, I think so - with this kind of stuff it’s conversational. If you can sing in a speech rhythm it’s incredibly effective and musically it’s gorgeous, but it’s a million miles from metronomic. I love that.

Rather than the pursuit of fame or fortune, the primary success of your career seems to me that you have been able to retain freedom and choice.

Yes, but I’ve been allowed to do that. It’s this privileged existence that I’ve lived. That’s what the folk scene does: it gives you as much room to move as you want. You’re loyal to it and it’s loyal to you.

Have you ever had to earn what we might describe as a "proper" living?

Have you ever had to earn what we might describe as a "proper" living?

Nope, never! The closest I ever came was the five or six weeks I went on the dole when I came out of theatre. I came off it because I went to my mum and said, “This isn’t right. There are people who need this. I don’t need it, I’m living at home and I’m happy and this is pocket money.” So I went out and sang in the coffee bars and got a free meal there and all the lemon tea I could drink, and sometimes I got my pound, which is what you got paid. The one job I did was doing washing up at London Zoo, just for a day. I got sent there by the dole, which was fine, but God there was a ferocious woman in charge who hated these upstarts coming in for the day. Perhaps that contributed to my desire to get off the dole.

Folk music at the moment is enjoying one of its periodic boom times. Do you feel positive about that?

I just hope it’s not going to get fat and lazy like it did in the 1970s, but there’s some very exciting stuff going on. People are taking this stuff and using it as they see fit, and that’s exciting. I make some good friends of mine a bit cross when I say that the only thing you can do that would hurt this music is to not sing it or play it. That will ensure that it dies – you can do anything else you like with it. It’s all up for discussion the whole time, and that’s what makes it interesting. You can make a total pig’s ear of a song and it's fine. It’s still a great song. You can't actually ruin a song.

What more would you like to achieve?

Just to get better at what I do. This is wonderful music. The more you find out, the more there is to find out.

Watch Martin Carthy perform "Georgie" in his back garden

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Add comment