Out of the shadows: Dylan’s Eighties reappraised | reviews, news & interviews

Out of the shadows: Dylan’s Eighties reappraised

Out of the shadows: Dylan’s Eighties reappraised

Bootleg Series co-producer Steve Berkowitz gives an insider’s run-down on the latest Bootleg Series release, 'Springtime in New York'

Dylan’s 1980s weren’t great in terms of critical acclaim. As an emerging new fan, I knew that first hand from the scathing reviews accorded Shot of Love by the British music press when it was released in the summer of 1981, it seemed about as welcome as a door-knocking Jehovah’s Witness first thing on a Sunday morning.

Saved’s proselytising may have tipped the balance. “The hand is in the hand” Picasso once remarked – describing the most reliable marker of an artists’ skill – and the hands raised up in the album art for 1980’s Saved stuck out in the wider culture like a very badly painted sore thumb. It was a step down from 1979’s Slow Train Coming, though you could still find powerful songs therein – “Pressing On”, “In the Garden”, “Solid Rock” – but the studio recordings paled against the live versions eventually unveiled, 37 years later, on volume 13 of the Bob Dylan Bootleg Series, Trouble No More.

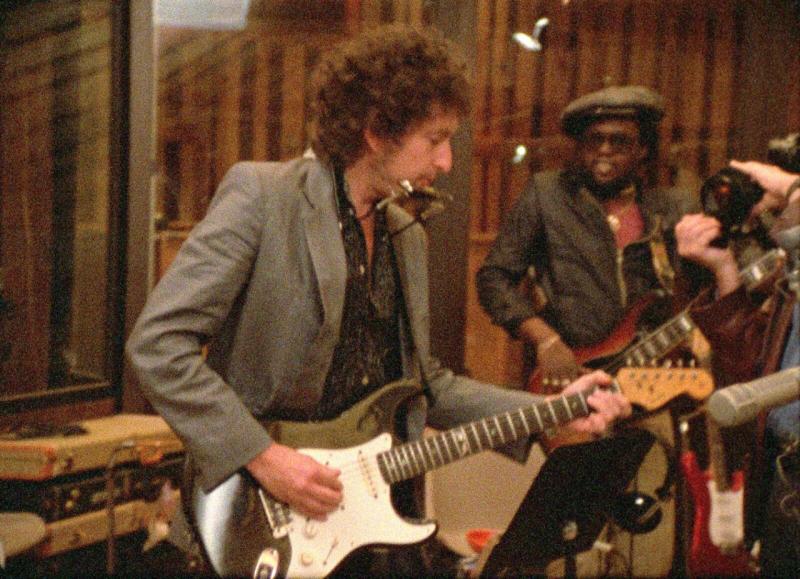

Roll on to Volume 16, and Springtime in New York more or less picks up where Saved left off, with dynamic tour rehearsals with his crack band featuring Fred Tackett, Tim Drummond and Jim Keltner, from the autumn of 1980 on Disc One of the full five-disc set; outtakes and alt-takes from the Spring of 1981’s Shot of Love fill Disc Two; 1983’s springtime sessions for the Mark Knopfler-produced Infidels cover Discs Three and Four; and a single disc from the winter of 1985 covers Empire Burlesque, slap-bang in the middle of the Eighties, and suffering somewhat under the production mores of that decade.

It was in the Eighties – more or less following the 1985 Biograph set – that discussion points centred less on what songs Dylan had included on the final track list of his albums, than on what he had left off, and for why. That, ultimately, is the key to the inner sanctum of this Springtime in New York set – the holy grail in the form of unreleased performances of major songs like “Angelina”, “Blind Willie McTell”, “New Danville Girl” and “Foot of Pride”, the latter a wild mix of the pithy and opaque which has three iterations, including its early life as the more tender, personal take on death, destiny and falls from grace, “Too Late”.

“The journey of ‘Too Late’ and ‘Foot of Pride’ is fascinating,” says series co-producer Steve Berkowitz, who has worked on all of Dylan’s Bootleg series releases. “To listen to the three takes included, to me that’s the listen. There’s the acoustic version, then the full band version, and a couple of days later it becomes ‘Foot of Pride’. That’s the journey, and it’s a fascinating journey. For me, those three versions are a really big deal. Each take is important, and I like that we put out one in advance and people reacted to it really well.”

Berkowitz is talking from a studio on the US east coast, the first time, he says, he’s been in one in 18 months, working on some archival Miles Davis tapes for future release. He’s passionate and knowledgable about the music Dylan made during what critics call his “lost” Eighties, but he’s no fan of the kind of critical flack that dogged Dylan’s releases through that decade, arguing more for an approach that ditches expectations and projections.

“If your job is to be a critic and you have a particular point of view, and you think and expect that this is what this artist should do for you, then the whole idea of criticism is off the wall right there,” he says, “because what the hell are you talking about? We’re talking about what the artist is doing, in an overall canon. It’s like Miles, like Picasso. You can’t look at Picasso and say, ‘man I love that blue stuff with the guitars, but what’s that crap with the eye outside of its head?’ You’re talking about Picasso, Jack, so you should step back and try to get the whole thing in, try to understand the journey that he’s taking. You can hate it all you want, and traditionally a lot of critics have thought poorly of Shot of Love through to Empire Burlesque. But I don’t ever think that way, and it’s not for me to judge when the genius is on or back or off; you should just pay attention.”

“If your job is to be a critic and you have a particular point of view, and you think and expect that this is what this artist should do for you, then the whole idea of criticism is off the wall right there,” he says, “because what the hell are you talking about? We’re talking about what the artist is doing, in an overall canon. It’s like Miles, like Picasso. You can’t look at Picasso and say, ‘man I love that blue stuff with the guitars, but what’s that crap with the eye outside of its head?’ You’re talking about Picasso, Jack, so you should step back and try to get the whole thing in, try to understand the journey that he’s taking. You can hate it all you want, and traditionally a lot of critics have thought poorly of Shot of Love through to Empire Burlesque. But I don’t ever think that way, and it’s not for me to judge when the genius is on or back or off; you should just pay attention.”

There’s plenty to attend to – 57 tracks across five discs, or a more curated 2CD set picking 25 of the stand-out cuts, as well as vinyl formats, all drawn from hundreds of hours of archive that a dedicated team pulls together for the selection process.

“What gets lined up ahead of time, together with Jeff Rosen, archivists Parker Fishel and Glenn Korman, and the Dylan office, is to seek all of the material from the time period, whatever format it’s in. We gather it together, put it chronologically, whatever happened, who did that, who said what, what other rehearsals are there.”

The array of original formats they had to deal with and convert into high-definition digital audio included analog two, eight and 16-track rehearsals, alongside 24 and 32-track early digital recordings, in formats that have long since passed into a dark and chilly technological Hades. Fortunately, there were a couple of machines left that could bring them back to life. “There’s a guy in New Jersey who has one of these machines,” says Berkowitz, “and I think we brought it to Battery Studios [Sony’s in-house facility in what was one The Record Plant]. There’s also a guy in Nashville – those are the only two known working versions of that Sony machine that exist. With the guy in Nashville, we brought the tape to the machine, because you can’t really move them around; there’s so few of them left.”

A few more years down the line, and retrieving any of it could have proved impossible, which underlines, in the 2020s, the increasing urgency of digital archiving, given the limited life span of some of those original sources. “There’s now a decade’s worth of deep, deep archiving,” says Berkowitz, “to save everything before the machines die, before the tapes fall apart, before there aren’t any humans who know how to operate the machines anymore.”

Having converted each and every session and rehearsal tape into high-definition digital audio, the curatorial work took precedent. Some Bootleg Series sets have gone for the completist approach – notably The Cutting Edge series from 1965-1966, and The Basement Tapes – but Springtime was always going to be a curated set. “It wasn’t our goal to be completist,” says Berkowitz of the process, “it was to tell the story from here to there. We listened to everything, to thousands of tracks,” he adds. But when you’re confronted with, say, 47 takes of “Foot of Pride”, what guides the final choices you make?

The best of the songs and the best performances raise their own hands, and that instructs what really stands out

“I’ll tell you right upfront – I don’t know how the final decisions are made,” says Berkowitz, “and I’m not being coy with you. The final decisions come back from Jeff Rosen and the Dylan office. Bob Dylan’s contract says that he can decide whatever he wants. Though I couldn’t tell you exactly how the answers come back.” What he does know is that he and Dylan’s manager Jeff Rosen share a similar approach when it comes to sifting the raw archive for nuggets of gold. “What we think we hear is that the best of the songs and the best performances raise their own hands, and that instructs what really stands out.”

Berkowitz’s mission as the set’s co-producer was to follow the story. “And show the journey,” he says, “from pre Shot of Love through Infidels, through to Empire Burlesque, with him in the studio clearly seeking, pushing. He’s trying, and the fact is, there are great songs in here. And they’re presented in various ways. And I make no criticism nor comment about the albums as they came out, but we thought, like with some of the other sets, let’s strip it down to a verite of what they did in the studio at that time. And how it came together, or didn’t come together, in relationship to the way you think a song gets finished.”

You can hear that journey in the tentative, fragile, exploratory take of the haunting, otherworldly “Angelina” from Rundown Studios in the spring of 1981. Were there more versions of that spectral, vision-haunted song that could have been included? “There were a lot of stop and start cuts,” says Berkowitz. “But this version, again, raised its hand with its delicacy, its beauty, in focusing on the lyrics. I thought it was beautiful and it needed to be here. While the other ones were not as … I mean, are we being completist or not? Our goal was to tell the story, and to focus on some of the tracks that are masterpieces, that had never come out in this form before. ‘New Danville Girl’, ‘Angelina’, certainly ‘Foot of Pride’. It’s a journey and it’s very diverse. I think ‘Fur Slippers’ is really great. And ‘Let’s Keep it Between Us’. The ballads are beautiful. The version of ‘I&I’ on Disc Four, that’s a fantastic version. It’s unbelievable how he focuses on it.”

His own songwriter’s workings aside, there are some memorable cover versions here, from Hank Williams to Neil Diamond via Willie Nelson and Jimmy Reed, with a touch of Shel Silverstein thrown in. With the best – a powerful, driving “Mystery Train” that features Jim Keltner AND Ringo Starr on drums, Donald “Duck” Dunn on bass, and saxophonist Steve Douglas – Dylan doesn’t just inhabit the song, he haunts it and drives it like a runaway train.

“Some of the Rundown stuff is just fantastically musically,” affirms Berkowitz. “‘This Night Won’t Last Forever’ – that was a surprise. A huge mind blower for me was ‘I Wish It Would Rain’ on Disc Two. After ‘The Price of Love’, which is a really fun song. Bob Dylan singing falsetto – you don’t get that very often. ‘Your Cold Cold Heart’, that’s on eight track, and he sort of slams into it, and it’s the one and only version, and there it is.”

“Some of the Rundown stuff is just fantastically musically,” affirms Berkowitz. “‘This Night Won’t Last Forever’ – that was a surprise. A huge mind blower for me was ‘I Wish It Would Rain’ on Disc Two. After ‘The Price of Love’, which is a really fun song. Bob Dylan singing falsetto – you don’t get that very often. ‘Your Cold Cold Heart’, that’s on eight track, and he sort of slams into it, and it’s the one and only version, and there it is.”

Such one-and-only performances are the raison d’etre of the Bootleg series – caught in the moment, flaring bright, and then forgotten again, until now. “You think about his ability as a songwriter,” says Berkowitz, “and his ability to understand a song, whether it’s the standards records of the past 10 years, or doing something with ‘I Wish it Would Rain’ or ‘Mystery Train’, but Bob understands the feel of the music on those songs – why wouldn’t he sing the shit out of them? This box allows you to hear that journey in a verite way, with Bob Dylan and the songs, him writing the songs and morphing them, and you get to hear that, before they committed to the production style of that time. You get to hear what he left out, like the masterpiece that is ‘New Danville Girl’.”

Of course, there’s plenty that didn’t make the final cut of Springtime, and while no one’s asking for his 1985 Live Aid set, there have been pleas for the first 1985 Farm Aid performance with Tom Petty, which featured songs from the-then just released Empire Burlesque, and for the rest of the Letterman performances with The Plugz (only “License to Kill” is included). Then there are the fabled Dylan-Clydie King duets, of which “Abraham Martin and John”, on Disc One of the full set, is the most arresting. “We’ve put on some others, like ‘Fur Slippers’,” says Berkowitz, “and we released some really great stuff between Bob and Clydie on Trouble No More. There is more,” he adds, “but there’s nothing great that we held back.”

So, does Springtime retrieve and reorientate the first half, at least, of Dylan’s “lost” decade? The journey I hear is one from Dylan’s well-scuffed home turf – Santa Monica’s Rundown Studios, which he kept from 1978 through to 1982, and whose grungy-looking entrance features on the cover of Street-Legal – to becoming a stranger in a strange land, negotiating the unfamiliar sonic landscape of the Eighties with songs that he knew and songs that could only have come to him, and from him, at that point, as he stepped away from the congregation and returned to a folk-blues source in songs like “Blind Willie McTell”, while later you can hear him looking for new ways to express his poetry, filtered through the mores of mid-Eighties pop, with the kind of ballad that elevates Empire Burlesque – “I’ll Remember You” and “Emotionally Yours”, both of which feature here in superior, unadorned, and tenderly sung versions.

Rather than seeing the set as a re-evaluation along the lines of, say, Another Self Portrait, for Berkowitz it is more a revealing of what was really there, after removing the obscuring aural varnish of reverb and backwards gated snare drums – the sound of the decade to which these songs hitched their horses. Springtime strips away all that. “It is an expose, a verite, of the music they made,” says Berkowitz, “and a revealing of the seeking that this artist was doing. And trying it like this, and trying it like that. It’s going back to a side view of the journey and what really went down in the studio, not with the final production on it. Hopefully, that is what we have achieved, so that you can get at the essence of what Bob was going for.”

Rather than seeing the set as a re-evaluation along the lines of, say, Another Self Portrait, for Berkowitz it is more a revealing of what was really there, after removing the obscuring aural varnish of reverb and backwards gated snare drums – the sound of the decade to which these songs hitched their horses. Springtime strips away all that. “It is an expose, a verite, of the music they made,” says Berkowitz, “and a revealing of the seeking that this artist was doing. And trying it like this, and trying it like that. It’s going back to a side view of the journey and what really went down in the studio, not with the final production on it. Hopefully, that is what we have achieved, so that you can get at the essence of what Bob was going for.”

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Album: Robert Plant - Saving Grace

Mellow delight from former Zep lead

Album: Robert Plant - Saving Grace

Mellow delight from former Zep lead

Brìghde Chaimbeul, Round Chapel review - enchantment in East London

Inscrutable purveyor of experimental Celtic music summons creepiness and intensity

Brìghde Chaimbeul, Round Chapel review - enchantment in East London

Inscrutable purveyor of experimental Celtic music summons creepiness and intensity

Album: NewDad - Altar

The hard-gigging trio yearns for old Ireland – and blasts music biz exploitation

Album: NewDad - Altar

The hard-gigging trio yearns for old Ireland – and blasts music biz exploitation

First Person: Musician ALA.NI on how thoughts of empire and reparation influenced a song

She usually sings about affairs of the heart - 'TIEF' is different, explains the star

First Person: Musician ALA.NI on how thoughts of empire and reparation influenced a song

She usually sings about affairs of the heart - 'TIEF' is different, explains the star

Album: The Divine Comedy - Rainy Sunday Afternoon

Neil Hannon takes stock, and the result will certainly keep his existing crowd happy

Album: The Divine Comedy - Rainy Sunday Afternoon

Neil Hannon takes stock, and the result will certainly keep his existing crowd happy

Music Reissues Weekly: Robyn - Robyn 20th-Anniversary Edition

Landmark Swedish pop album hits shops one more time

Music Reissues Weekly: Robyn - Robyn 20th-Anniversary Edition

Landmark Swedish pop album hits shops one more time

Album: Twenty One Pilots - Breach

Ohio mainstream superstar duo wrap up their 10 year narrative

Album: Twenty One Pilots - Breach

Ohio mainstream superstar duo wrap up their 10 year narrative

Album: Ed Sheeran - Play

A mound of ear displeasure to add to the global superstar's already gigantic stockpile

Album: Ed Sheeran - Play

A mound of ear displeasure to add to the global superstar's already gigantic stockpile

Album: Motion City Soundtrack - The Same Old Wasted Wonderful World

A solid return for the emo veterans

Album: Motion City Soundtrack - The Same Old Wasted Wonderful World

A solid return for the emo veterans

Album: Baxter Dury - Allbarone

The don diversifies into disco

Album: Baxter Dury - Allbarone

The don diversifies into disco

Album: Yasmine Hamdan - I Remember I Forget بنسى وبتذكر

Paris-based Lebanese electronica stylist reacts to current-day world affairs

Album: Yasmine Hamdan - I Remember I Forget بنسى وبتذكر

Paris-based Lebanese electronica stylist reacts to current-day world affairs

theartsdesk on Vinyl 92: Marianne Faithful, Crayola Lectern, UK Subs, Black Lips, Stax, Dennis Bovell and more

The biggest, best record reviews in the known universe

theartsdesk on Vinyl 92: Marianne Faithful, Crayola Lectern, UK Subs, Black Lips, Stax, Dennis Bovell and more

The biggest, best record reviews in the known universe

Add comment