The last of the old maestros is standing tall. Marco Bellocchio was a Marxist firebrand when he made his iconoclastic debut with Fists in the Pocket (1965). Now aged 84, he makes intellectually and emotionally muscular, hit epics about abused Italian power.

The Red Brigades’ fatal 1978 kidnap of former, reforming Prime Minister Aldo Moro in Good Morning, Night (2003) was followed by Mussolini’s persecution of his mistress and illegitimate son in Vincere (2009), a haunted turncoat’s survival of the Sicilian Mafia’s apocalyptic Eighties in The Traitor (2019), and a return to Moro in the six-hour Exterior Night (2022).

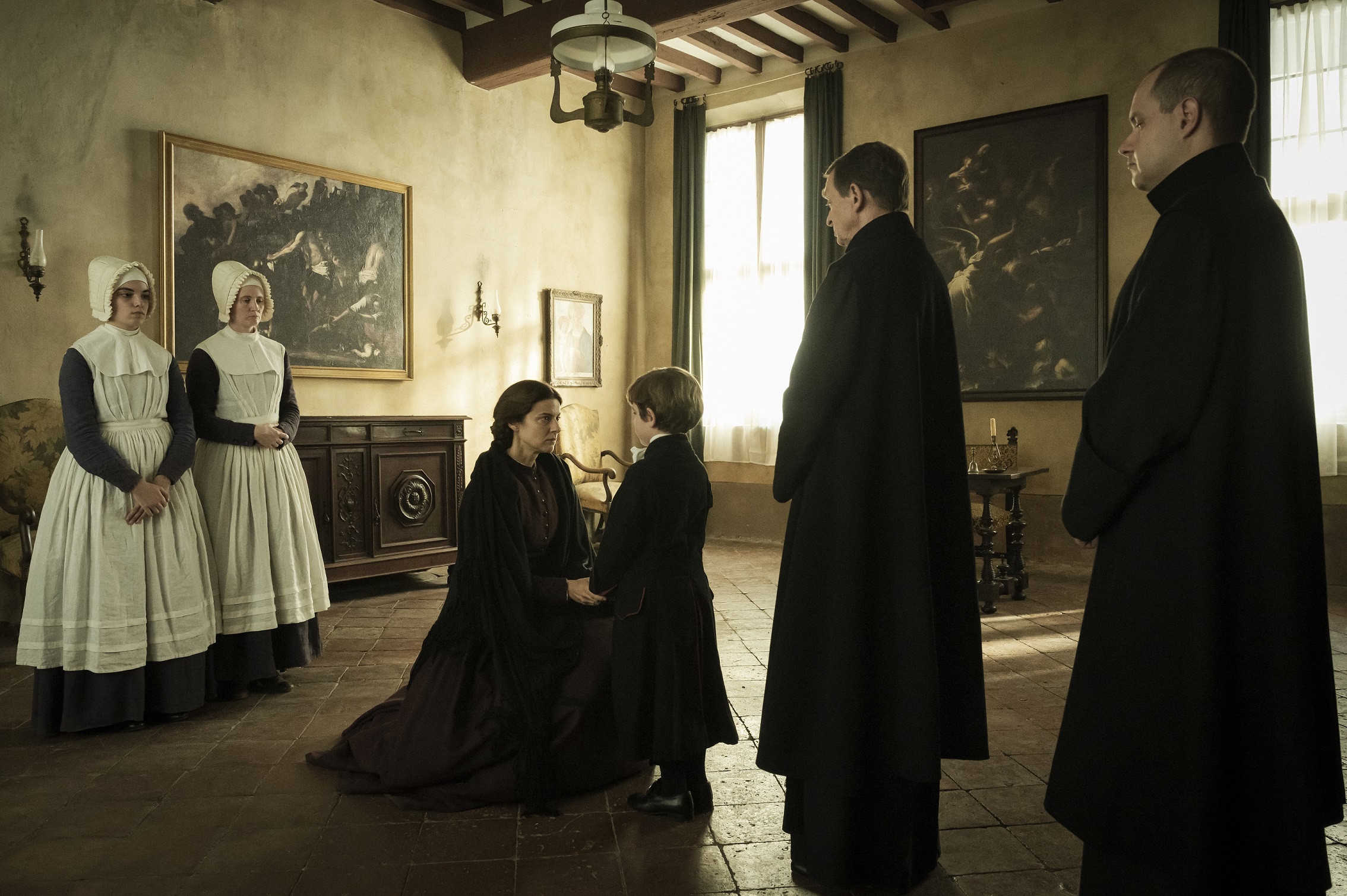

Now Kidnapped illuminates the Catholic church’s violent 1858 snatching of a young, seemingly baptised Jewish boy, Edgardo Mortara, from his family. He is taken across fogbound, Styx-like Venice waters, a passage perhaps of no return to a life in Papal palaces shot in candlelit tableaus, modelled by Bellocchio on Italian romantic painters such as Delacroix.

As with his other sagas, period politesse and realism are ruptured. Pope Pius IX rants against European outrage at the kidnap with spittle-scummed lips, but dreams of being circumcised by vengeful Jews in a wild antisemitic nightmare. Good Morning, Night also enters the realm of dreams and magic when a ghostly Moro finally walks away from his captors, like Christ leaving Gethsemane, as if that Italian trauma could be woken from. Kidnapped similarly sees Edgardo reach his hand out to a carving of Christ and lead him down from the cross, childishly healing the rift the church opened in his Jewish soul.

As with his other sagas, period politesse and realism are ruptured. Pope Pius IX rants against European outrage at the kidnap with spittle-scummed lips, but dreams of being circumcised by vengeful Jews in a wild antisemitic nightmare. Good Morning, Night also enters the realm of dreams and magic when a ghostly Moro finally walks away from his captors, like Christ leaving Gethsemane, as if that Italian trauma could be woken from. Kidnapped similarly sees Edgardo reach his hand out to a carving of Christ and lead him down from the cross, childishly healing the rift the church opened in his Jewish soul.

Bellocchio matches his octogenarian peer Scorsese for heady, innovative mayhem, The Traitor’s screen counter ticking over at each Mob death predating The Irishman’s predictive morgue inscriptions for its doomed gangsters. In Kidnapped, a chaotic papal funeral and the sacking of the Papal States looks like anticlericalism as action movie from this old Communist. In fact, the mature Marco sees religion’s loving good, loathes its abuse and, though still radical, abandoned his party card for psychological enquiry long ago. The battling models of his deeply Catholic mum and Communist dad have made humane peace. Again like Scorsese, there is dark humour, too. “The Inquisition,” mutters one of Edgardo’s family. “They’re worse schmutzes than the pharaohs.”

Some themes endure through the decades. A rebel, unloved son killed his mother in Fists in the Pocket, and the childhood mystery of his mother’s death haunts a son in Sweet Dreams (2017). Now, Edgardo and his mum’s pain at living loss sears Kidnapped. Bellocchio’s own great wound, his twin brother Camillo’s 1968 suicide, has meanwhile powered The Eyes, the Mouth (1982) and his recent documentary, Marx Can Wait (2022), which accepted and laid to rest family guilt.

Fellini and Bertolucci faded at the end, Bellocchio’s friend Pasolini was cut down in his prime. Bellocchio has instead joined Italy’s new generation of maestros – Paolo Sorrentino, Matteo Garrone and Alice Rohrwacher.

Meeting him at his UK distributor’s London office on a warm spring evening, it’s no wonder. Never the sartorial rebel even during his Sixties spell at London’s Slade School of Fine Art, he’s crisply dressed in casual suit and shirt. White-haired and handsome, he could be 20 years younger. He talks with extravagant enthusiasm, testing his translator’s endurance. You would think he was just getting started.

NICK HASTED: Is Edgardo's conversion more interesting to you than his kidnap - the way he succumbs to his fate?

NICK HASTED: Is Edgardo's conversion more interesting to you than his kidnap - the way he succumbs to his fate?

MARCO BELLOCCHIO: There are obviously different aspects that attracted me to the story and the “conversion” is definitely an important one, but perhaps not in the surface meaning of what a conversion is. Because there is a line of thought that was pushed about that this conversion was a direct action by the Holy Spirit who possessed the child and made him see the error of his ways as a Jewish child, and the truth of the Catholic faith. But I wanted to portray the disconnection between his real family and his acquired family in the Catholic church. Because his new “father" the Pope, who took such a personal interest in this child, is also his kidnapper. The mystery is that once Rome was liberated and the now adolescent could have chosen to leave, he doesn’t. But we see in certain junctions in the film that there is still a struggle going on. Like, for instance, when his parents go and see him in the seminar when he’s still a child, suddenly what seemed to be a resolved internal conflict makes him say, “I want to come home, I want to go back to my siblings.”

So was this resolved, or was it never resolved during the course of his life? Edgardo wrote a short autobiography, and for sure we don't know a lot of his inner thinking, but we know that he suffered a lot of unexplained illnesses in his life. So was it Stockholm syndrome, the fact that he didn’t go back, or was he really certain in this newly imposed, but then accepted faith in the Catholic church? I was not attracted by the idea of a conversion, but in what it signifies to be converted in this exceptional way, something that I obviously don’t subscribe to as an imposition, especially on a child, especially in the form of a total violent uprooting from his family.

Sometimes the antisemitism and the violence towards Edgardo is quite quiet. It's not as naked as a pogrom, but a pressing down, a silencing - a suppression.

Sometimes the antisemitism and the violence towards Edgardo is quite quiet. It's not as naked as a pogrom, but a pressing down, a silencing - a suppression.

That actually reflects what going on historically at that time, not only in Italy and Europe, but also in the United States. We are way before the really violent suppression that we saw in the 20th century. But we are on the cusp of so many watershed moments in thinking and political actions in that historical period in Italy. The violent uprooting and kidnapping of this child becomes a cause celebre because the Pope feels that his millennial power as a head of state is waning and crumbling. We also see the move away from religious thinking into more political and lay thinking in Italy after its reunification, when people from different creeds will be treated as citizens and not subdivided. So the reason why the Pope cannot give in is because that would be an admission that his historical moment has declined beyond any recognition. If you think of that scene when the Pope has the nightmare of being circumcised, a theatrical company in Boston actually performed a play which showed exactly that scene. And in the film, upon hearing this, the Pope internalizes his fear that this may actually happen. The Boston play was a parody. But in itself that puts into question the untouchability of the authority and power of the church.

So it’s not that this type of kidnapping by the Catholic church in the case of real or alleged baptism didn’t go on before - and this was the penultimate case, not the last. But even though this was quite a common occurrence in the 18th century it was coming to an end, because it was harking to the past, and not true to the historical moment. Even when such important figures as Napoleon III, the Rothschild who actually lent the Vatican an enormous amount of money and people from the UK opposed this, there was that monolithic denial from the Pope to concede, because that would’ve meant the end of his true authority.

The cinematography is gorgeous, it seems candlelit and I know it was partly inspired by 19th century painting, Delacroix and so on. You also use long-shots showing grandeur and scale. How does that visual language relate to what happens to Edgardo?

The cinematography is gorgeous, it seems candlelit and I know it was partly inspired by 19th century painting, Delacroix and so on. You also use long-shots showing grandeur and scale. How does that visual language relate to what happens to Edgardo?

If we bear in mind the point of view of the child and his background, it was important to convey that part of his seduction in being converted to the Catholic religion was that because of the nature of his [Jewish] religion at birth, he’d never seen the depiction of saints or churches of that scale. For us, if we have Catholic backgrounds, we’ve been exposed to those vivid images when we were preverbal. It's hard to imagine the impact that must have had on a small child, and what it is to see that image of a bleeding dead man being nailed to a cross. There is that visual shock. And also in those shots of the [huge Catholic] dormitory, for instance, you see the difference in scale of all those children sleeping together, when in Edgardo’s home all the eight children were sleeping very, very close in the same room. So in medium-shots and long-shots, you see the scale of what the Catholic church was proposing to the child.

You said in an interview a few years ago, Marco, that: “I don't believe in the inexorability of history.” And whether it's in that scene where Edgardo lets Christ down off the cross, or Aldo Moro walking free at the end of Good Morning, Night (Maya Sansa pictured above in this film), it seems like sometimes there’s the possibility and power of dreaming, even magic in your films - these moments of imaginative healing or bliss, where you are not determined by the history the film is telling.

Yes, for sure. And obviously without denying the historical facts of the story, I reserve for myself the freedom of artistic imaginings embedded in the real historical settings. So that gives you the freedom to morally imagine what would've happened had Aldo Moro been freed, which was actually the collective hope, and almost the belief of a lot of Italians at the time. And in the scene that you mentioned in Kidnapped, the child wants to free the Christ, but also by freeing him, perhaps the child wished to make the two faiths coexist. Because by freeing the Christ, then that opposition, that dichotomy between his Jewish background and the Catholic faith would be reconciled, because the Christ was not on the cross any longer.

Do you relate to Catholicism and Marxism as two lost faiths? And what has replaced them in how you see the world in your films? Is there less certainty, more doubt and more forgiveness?

Do you relate to Catholicism and Marxism as two lost faiths? And what has replaced them in how you see the world in your films? Is there less certainty, more doubt and more forgiveness?

Yes, there are two sets of beliefs, but they’re very different, insomuch as Catholicism is something that moulded me over the years. Marxism was a utopian faith very much shorter in time, but what that left behind is an interest in other people, a distrust and a dislike towards authority. And I almost describe himself as an anarchist, but a nonviolent anarchist, I wouldn't plant bombs or wish the death of anybody. On reflection, I’m not bitter, I’m not resentful at all. And that could be because I describe myself as having had a good, lucky life.

A lot of your recent films – Vincere, Exterior Night, The Traitor (pictured above), this film - show an abuse of different forms of power in Italy in different times in quite an epic way. Do all of these films together tell a sort of Italian tragedy, with the hope for something better?

Not really limited to Italy, but in my life I've seen so many different historical moments. There were moments like in 1968 when you could breathe an air of hope that the stale power system could be subverted. Then as we know, that dissipated. So at that point, perhaps it went more into an introspective journey psychologically, but collectively, not on the individual point of view, and there are so many different schools of thought. Mental wellness is something that is really interesting to me. There are people who maintain that we are all mad. But I really delved deeply into that sort of work. Right now, I'm still an optimist, but there are no political parties that I can identify with. At a certain point, the Italian Radical Party led by Marco Pannella [which dissolved in 1989] was pushing certain things that resonated with me. But right now I feels political with a small “p” action is making movies because, touching wood, I’m in good health, and very lucid. And through that storytelling I can present different visions that resonate on a political but also on an emotional level.

Add comment