One of the most exciting new voices in Eastern European film, Déa Kulumbegashvili is not concerned with conventional shot lengths. She has been described as a director of "slow cinema", which she regards as a compliment.

Kulumbegashvili's intention is to create an imaginative space that uncovers the truths behind patriarchal expectations and misogyny, without ever limiting the viewer's experience or agency. Characterized by carefully crafted but disorienting compositions, her storytelling is fiercely confrontational.

Her second feature, April, combines revealing social realism with horrific expressionism. It centres on Nina (Ia Suchitaschwili, pictured below), an obstetrician who finds herself under investigation at the hospital where she works following a stillbirth. What's more, she's under scrutiny for performing secret abortions in local villages – a taboo in rural Georgia. Riddled with religious dogma, the society that April exposes has nothing but contempt for its victims.  Kulumbegashvili's film is overpoweringly visceral – the violence and oppressiveness hardly mitigated by its bleak painterly beauty. Static shots of thundery skies and Nina's night-time drives are stretched out for minutes, but they never drag; it is the persistence of the images that builds tension. (What Nina seeks on those drives compounds her mysteriousness.)

Kulumbegashvili's film is overpoweringly visceral – the violence and oppressiveness hardly mitigated by its bleak painterly beauty. Static shots of thundery skies and Nina's night-time drives are stretched out for minutes, but they never drag; it is the persistence of the images that builds tension. (What Nina seeks on those drives compounds her mysteriousness.)

Complementing the brutishness of much of Kulumbegashvili's imagery, the camera angles frequently reflect the characters' skewed perspectives. If they're off-camera, their presence is rendered palpable by their speech and their breathing; sometimes it's just a hand that reaches into the frame. Kulumbegashvili knows how to create an uncomfortable imbalance in her mise-en-scène, sometimes by pushing the characters to the edges of the frame and surrounding them in dead (but repulsive) space accompanied by eerie sounds.

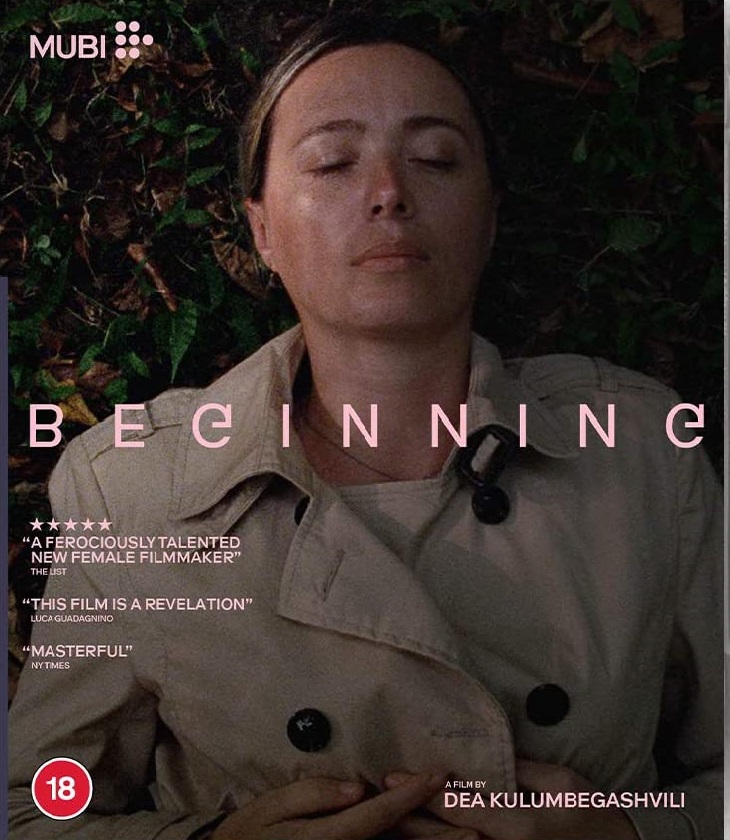

Motherhood is the topic underpinning the director’s work. Her debut Beginning, a chilling domestic thriller about the disillusioned wife (Suchitaschwili) of a Jehovah’s Witness missionary, unfolds in the same rural Georgian community where April takes place. Talking over Zoom, Kulumbegashvili (pictured below) says, "I love my country, but it is a very troubled place."

Pamela Jahn: What is the first thing that comes to mind when you think about giving birth?

Pamela Jahn: What is the first thing that comes to mind when you think about giving birth?

Déa Kulumbegashvili: It's interesting that you ask, because since becoming a mother myself, I have different feelings about it. On the one hand, it's something very irrational because nothing really depends on you – it's that ultimate moment of having no control. Yet, at the same time, it's also the most selfish or maybe self-centred experience. It's weird and wonderful.

Like your previous film, April tells another very female-centred story. Do you feel specifically drawn to women characters?

I was always very preoccupied with questions about womanhood – and motherhood, in particular – even before I had my own child. I have very complex relationships with my own mother and also my grandmother. I feel a lot of admiration for them and understand the difficult decisions they had to make in their lives. With April, things changed considerably, though, as I went back to the editing room. At the time, my child was only three weeks old, but I felt some sort of urgency to revisit the film.

What was different then?

I became more compassionate as a person. I don't want to be very sentimental about this, but I started to understand how difficult it is when you have no control over your child's life. Like, we think we do but, at the same time, we really don't. Specifically in this place where I made the film, both the women and children are so vulnerable and exposed, almost defenseless somehow. I have seen kids with scars because they were beaten up by their fathers, and as I was talking to their mothers, I could see how helpless they felt.

What makes this place, this rural stretch of eastern Georgia where you shot the film, so prone to violence?

What makes this place, this rural stretch of eastern Georgia where you shot the film, so prone to violence?

It's a place that is somewhat in between, a place at the periphery, far away from the capital. There is this feeling of being abandoned, and you get a sense that more extreme forms of human nature are able to manifest themselves in this area. I grew up in the region until I was 17. I experienced the Civil War, and I was aware of the drug trafficking that was going on. But at the same time, it's also a spectacularly beautiful place.

So, as a child I was always exposed to both sides, and not much has changed since then. History has left its imprint on this place. Femicide is a very frequent occurrence, especially in the villages which are remote. Yet, the Georgian government does not do anything to change the mentality or help prevent the violence against women. It's even encouraged to some extent, I feel, because they don't want to intervene in whatever goes on in families.

How did you go about finding the right tone for the story?

When I first started to talk about it with Ia Sukhitashvili (pictured above), the main actress, I was trying to look at the very down to earth aspect of giving birth and being born, because it's what makes us come to life in this material form. I wanted to see beyond the feelings and sentiments, and Ia, who is already a mother of two, felt very similar about it. Interestingly, for all the male actors, this thought was just unacceptable They were talking about their children almost in some mysterious way.

Why do you think that is?

It all comes down to our bodies as women. Whether it's giving birth or an abortion, it happens not to us, but through us – it's part of us. I had similar conversations with the women who helped me to make this film around the question of terminating their pregnancies. Most of them would be very practical about it. They were not trying to justify it. They just said that it was necessary. But deep inside they were conflicted emotionally; they still felt a strong sense of guilt. I always had this feeling that it was a sacred, almost ritualistic process. That's why I wanted to show the actual procedure for as long as it would really be going on. It was all done with precise instructions from doctors. We practised a lot, so it would become very mechanical.

Did you find it difficult to write the script because of the delicacy of the subject?

No, I love writing. For me, it's the most self-absorbed and very selfish process. So much of it happens in your head that you almost forget at some point what's written on paper and what is down to your imagination. In that way, the script, for me, is just a blueprint for the film, only 10 per cent is on the page and the rest I really hope comes through the images and through what's untold. It's a very dangerous territory, obviously, because every viewer brings something of their own to the film. I guess for me, writing and making films is like a relationship with the unknown.

What you say is very much in contrast to that specific staging of every single scene in your film. Does the formal rigour provide a certain gravity?

What you say is very much in contrast to that specific staging of every single scene in your film. Does the formal rigour provide a certain gravity?

Yes. And it gives me a sense of control. I remember that I made this short film called Lethe in 2016. I loved it because it was almost like a floating film that you could never really grasp. People would criticise me for it, saying the film had somewhat escaped. And I was so happy about that. I felt this way it had become something of its own. Of course, I know that's not actually possible, because with editing you just bring everything back to its real form. But I still believe that what you see on screen is not the full experience. It's what happens between you and the film that's the most important thing. Maybe what I'm trying to do is control part of the experience, to create circumstances for the magic to happen.

There is a haunting energy underlying the magic, or mystery. Where does that come from?

Probably from being Georgian. I love my country, but it is a very troubled place. I grew up with this mysticism, which is always present in our culture, because we never really take anything for granted or for what it is. We believe in what we don't see. My grandfather, who was a scientist, always told me these stories about a creature he used to encounter when he went out to the well to bring in water, and it was so convincing. I'm sure that I've seen that creature as well, even if it is impossible.

The film's eeriness is heightened by the score. How did you work with Matthew Herbert to build up the soundscape?

I wanted a full sound experience. And I never thought that he would be so incredibly open to really think about every detail, especially the breathing. There are scenes where even I ask myself sometimes if it's coming from Ia or whether that's part of the music. We created the whole rhythm of the film through Ia's breath, it's very subjective and told from her point of view. At the same time, you never know what's really going on in her mind, and that was very important for me. I always question the experience of my characters, because as humans, as viewers, we don't need to know everything about each other in order to understand.

Add comment