Antonioni was a poet of enervated alienation, sold, like early Godard, by profoundly beautiful actors, and perfected in the sun-bleached lassitude of Monica Vitti’s search for her missing friend in L’Avventura (1960).

He wandered the world after 1964, applying his hip imprimatur to cultures in flux, from a fantastic, sexy, paranoid Swinging London in Blow-Up (1966) to Communist China in Chung Kio, Cina (1972), and drew Jack Nicholson into his games of existential ennui in The Passenger (1975). Returning to Italy for one last Vitti film, The Mystery of Oberwald (1980), which he dismissed, Identification of a Woman (1982) was effectively his last testament, recapitulating all his themes.

Niccolò (Tomás Milián) is a middle-aged director back in Rome after a divorce, searching for a new muse and lover. Casually picking up his gynaecologist sister’s aristocratic patient Mavi (Daniela Silverio), he is persecuted by mysterious forces, leading to an attempted escape through fogbound countryside. Soon afterwards, Mavi vanishes, repeating L’Avventura’s pivot, and Niccolò takes up with young actress Ida (Christine Boisson, pictured bottom right with Milián) who, wishing to resolve his feelings, begins her own search for Mavi.

Antonioni collaborated with a co-writer of all his Sixties classics, Tonino Guerra, and Gerard Brach, co-writer of Polanski’s parallel violently paranoid cinema (a Blow-Up/Repulsion double-bill would make a knock-out outsiders’ autopsy of London then). The director’s regular cameraman, Carlo di Ponti, maximised his chances of catching his old lightning.

Antonioni collaborated with a co-writer of all his Sixties classics, Tonino Guerra, and Gerard Brach, co-writer of Polanski’s parallel violently paranoid cinema (a Blow-Up/Repulsion double-bill would make a knock-out outsiders’ autopsy of London then). The director’s regular cameraman, Carlo di Ponti, maximised his chances of catching his old lightning.

“The world has changed, our ideas have aged,” Niccolò nevertheless chides an old collaborator, something already apparent with Blow-Up’s inauthentic details and American hippies’ derisive rejection of Zabriskie Point (1970). Much as he ransacked late Sixties rock for the latter, ex-Ultraxox leader John Foxx’s score heads a soundtrack of synthpop stars such as Japan and OMD. There is a “sectarian” atmosphere among aristos ready to flee the country, Red graffiti and suspicious street characters in the shadows, but this is hardly a documentary response to Italy’s Years of Lead, more reflections of a man out of time. This 2K restoration catches its every autumnal hue.

Patience for an ageing auteur’s quest for meaning via beautiful young women has thinned since 1982. “He wanted to go deeper into the female universe,” Enrica Antonioni, his real-life muse since splitting with Vitti in 1970 and eventual wife, explains in an Extras interview. The film's two women equate to his English aristocrat first wife and younger, earthier Enrica, 18 when they started their relationship (he was almost 60), and mature by now, to his consternation.

Antonioni’s first explicit sex scenes, and the intimacy of Boisson on the loo, aren’t as indulgent as his subsequent, post-stroke mission to undress the great actresses of Europe in Beyond the Clouds, but their stilted, frenetic choreography isn’t a patch on Blow-Up’s more sensual, censor-busting heat. Milián, popular for playing crude cop anti-heroes, badly lacks the charisma of previous Antonioni men, and the female stars only adequately intrigue. Minor female roles, though, from Enrica’s jaunty cameo to cool sparring by teenager Lara Wendel (a dauntless star of dubious erotica and gialli who quit aged 26), confirm Antonioni’s hunt for what Niccolò calls “new faces, new facts”. Antonioni debuted with a version of The Postman Always Rings Twice, Story of a Love Affair (1950), and the bones of melodrama and noir beneath his distanced modernist surface remain here, in warning phone-calls, shadowy threat and enigmatic, alluring women. He exploits this early atmosphere with a 10-minute centrepiece of creeping, helpless dread as Niccolò drives Mavi into a rural world of white fog. When he stops, this ghostly interzone seems bound to pull them apart, physical threat replaced by the uncanny.

Antonioni debuted with a version of The Postman Always Rings Twice, Story of a Love Affair (1950), and the bones of melodrama and noir beneath his distanced modernist surface remain here, in warning phone-calls, shadowy threat and enigmatic, alluring women. He exploits this early atmosphere with a 10-minute centrepiece of creeping, helpless dread as Niccolò drives Mavi into a rural world of white fog. When he stops, this ghostly interzone seems bound to pull them apart, physical threat replaced by the uncanny.

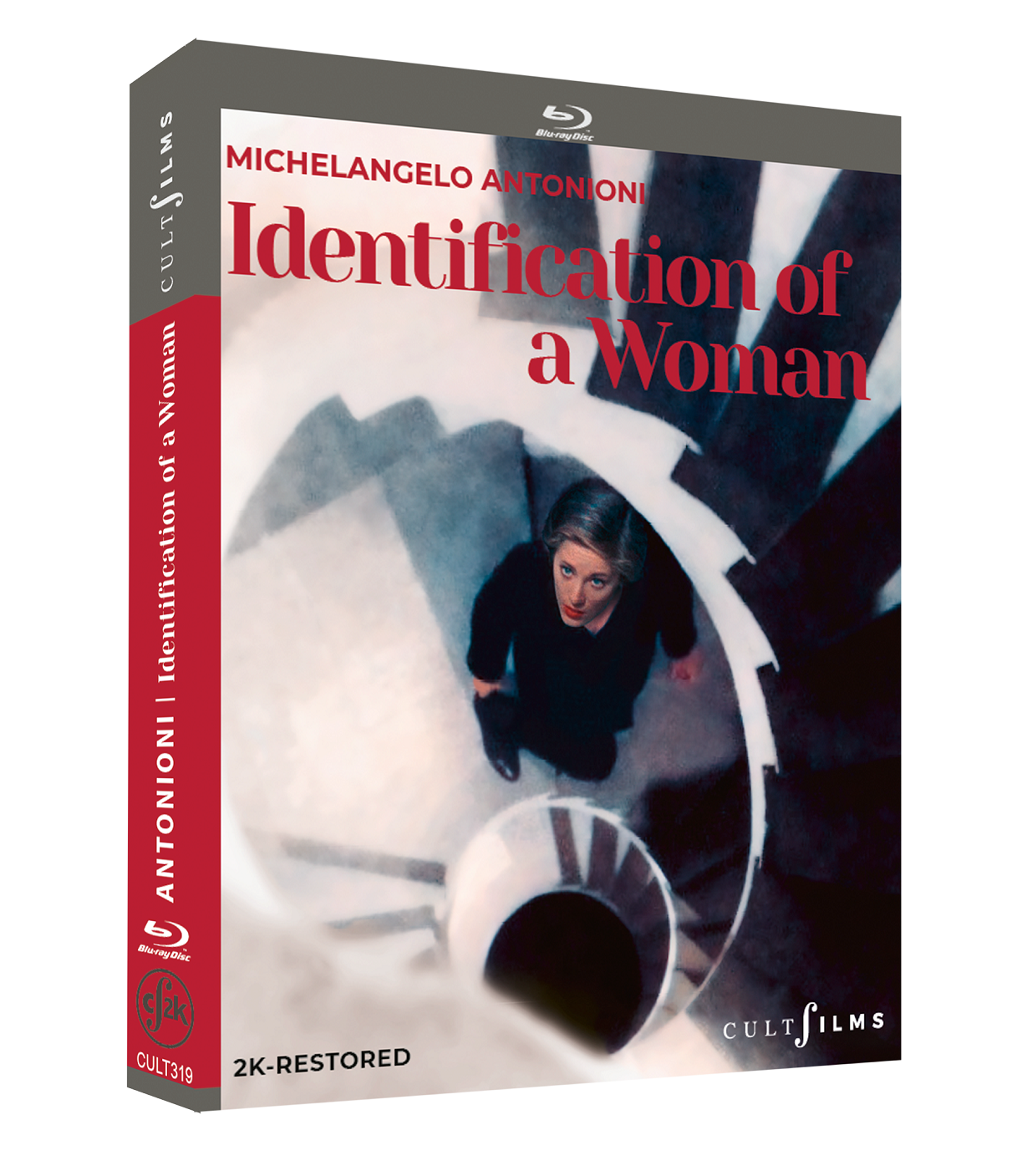

The film is worth it for this masterful scene. Though little love sparks between the actors, Antonioni’s exact, geometric framing adds an aesthetic sense of loss to Niccolò and Mavi’s last silent scene, matching concentric movements on a spiral staircase whose steps slice with a buzzsaw edge, before the camera’s classicist glide over Mavi’s shoulder towards Niccolò in the street below: gone, man. Antonioni’s erotic clumsiness and formal precision call late Kubrick to mind.

Enrica Antonioni’s buoyantly chatty and incisive insights are an Extras highlight, seeing no mystery in missing Mavi (“What woman doesn’t want to vanish?”), and noting Antonioni’s foggy hometown, Ferrara, as the source of the film’s white-out, anyway his favoured state: “He searched for emptiness because he found it aesthetically appealing”, always using “a camera from above that observes without any feeling”. Enrica’s film Con Michelangelo (2005) shows his post-stroke life, effortfully drafting visual art with her help, filling in his hard final act.

Add comment