Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years | reviews, news & interviews

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

At last Yoko Ono is being acknowledged in Britain as a major avant garde artist in her own right. It has been a long wait; last year was her 90th birthday! The problem, of course, was her relationship with John Lennon and perceptions of her as the Japanese weirdo who broke up the Beatles and led Lennon astray – down a crooked path to oddball, hippy happenings.

Most notorious were the Bed-ins which the couple staged in the late 1960s as a protest against the Vietnam war. At the heart of Tate Modern’s exhibition is the 1969 film BED PEACE in which we see the couple advocating peace from hotel rooms in Montreal and Amsterdam and recording the rousing song Give Peace a Chance, which became an anthem for the international peace movement.

Also on show are works from Ono’s 1966 exhibition at the Indica Gallery, London where she first met Lennon. There’s an apple left to rot on a perspex plynth (pictured right) from which, the story goes, Lennon took an illicit bite and a white board into which you are invited to drive a nail. When Ono demanded 5 shillings for the privilege, Lennon offered an imaginary payment to hammer an imaginary nail. Ono recognised a kindred spirit whose mind worked in similar ways to her own… and the rest is history. Although this section forms the centrepiece of the Tate exhibition, thankfully, Ono is given her due as an avant garde artist making waves internationally long before that fateful meeting.

Also on show are works from Ono’s 1966 exhibition at the Indica Gallery, London where she first met Lennon. There’s an apple left to rot on a perspex plynth (pictured right) from which, the story goes, Lennon took an illicit bite and a white board into which you are invited to drive a nail. When Ono demanded 5 shillings for the privilege, Lennon offered an imaginary payment to hammer an imaginary nail. Ono recognised a kindred spirit whose mind worked in similar ways to her own… and the rest is history. Although this section forms the centrepiece of the Tate exhibition, thankfully, Ono is given her due as an avant garde artist making waves internationally long before that fateful meeting.

As you step inside, a telephone rings. “Hello, this is Yoko” says a voice. Welcome to New York where, in 1960, Ono rented a loft at 112 Chambers Street in lower Manhattan and began staging events with composer La Monte Young. The loft became a focal point for multi-media performances involving artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, musicians like John Cage and David Tudor and dancers Trisha Brown and Yvonne Rainer – all of whom would later become household names.

Ono showed films such as Film no 1 (Match) in which she lights a match and holds it ’til it goes out. Filmed in slow motion, the match continues to burn for five mesmerising minutes. Slow motion similarly turns the blink of an eye into a dreamy meditation and transforms an involuntary action into a knowing sign. Recordings of everyday sounds such as Cough Piece (polite coughing) and Toilet Piece (a flushing loo) were incorporated into concerts comprising atonal music and freeform vocals performed by the artist and others.

Ono also wrote instructions for paintings that might or might not be realised. The painting to hammer a nail into originated here along with ideas that, like her films, explore space and time. "Place a stone under dripping water. The painting ends when a hole is drilled in the stone with the drops.” In 1964 she published Grapefruit, a delightful little book comprising 200 of these instructions inviting you, for instance, to “make a recording of the sound of snow falling”. She described these Zen-like instructions as scores that “lead you into a different dimension of thought”. It’s impossible to overstate just how influential were these left of field ideas. The conceptual artist Lawrence Weiner, for instance, would later built an entire career out of writing similar instructions.

Ono also wrote instructions for paintings that might or might not be realised. The painting to hammer a nail into originated here along with ideas that, like her films, explore space and time. "Place a stone under dripping water. The painting ends when a hole is drilled in the stone with the drops.” In 1964 she published Grapefruit, a delightful little book comprising 200 of these instructions inviting you, for instance, to “make a recording of the sound of snow falling”. She described these Zen-like instructions as scores that “lead you into a different dimension of thought”. It’s impossible to overstate just how influential were these left of field ideas. The conceptual artist Lawrence Weiner, for instance, would later built an entire career out of writing similar instructions.

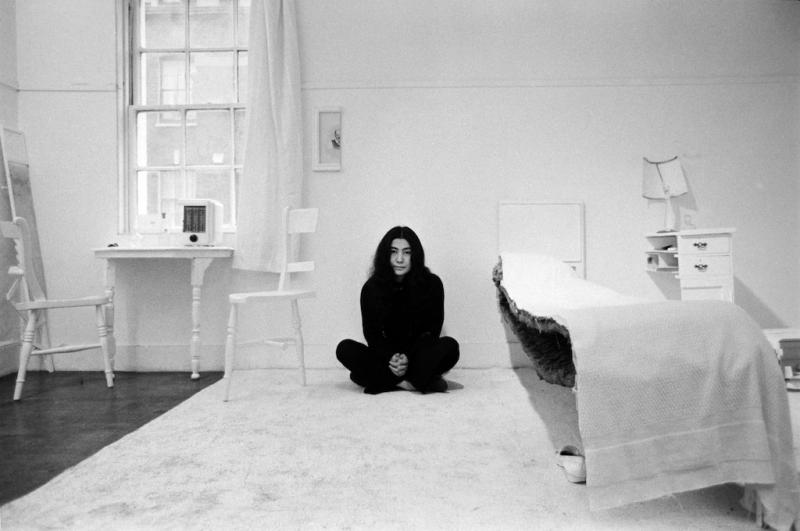

Her first solo show was in 1961 in Manhattan’s AG Gallery, owned by George Maciunas who later founded Fluxus, an international group of multi-media artists of which Ono was one. The following year she returned to Tokyo where she’d been brought up and continued performing with Tokyo’s avant garde artists. She brought John Cage and David Tudor over from the States and appeared with them on a concert tour. In Kyoto, for instance, she staged her seminal Cut Piece (pictured above left), which has been performed many times since. On film, we see the Carnegie Hall version made the following year on her return to New York. Ono kneels on the floor as, one after another, audience members come and cut off bits of her clothing. She becomes increasingly agitated as a grinning young man cuts through both bras straps. Six years later, as a gesture of solidarity with the women’s movement, she would film herself struggling to break free from the confines of her bras.

One of Ono’s greatest skills is to generate simple yet iconic images. Her 1966 Bottoms film (pictured below right) is a case in point. One after another, people stripped off to walk a treadmill, their naked buttocks undulating gracefully as they moved. When the film came out in 1967, the censors banned it for indecency but later relented and gave it an X certificate. It’s hard to see how anyone could be offended by this disarmingly innocent display of flesh, described by the artist as “the London scene today”.

Fly (1971) (pictured below) is far more disconcerting. A naked woman (Virginia Lust) lies immobile while a fly explores the nooks and crannies of her body. She doesn’t flinch as the insect probes her lips, explores her pubic hair or perches on a nipple cleaning itself. Seen in extreme close-up, her body and face become a landscape over which the insect is free to roam and unwittingly violate her private space, yet she remains resolutely calm.

Fly (1971) (pictured below) is far more disconcerting. A naked woman (Virginia Lust) lies immobile while a fly explores the nooks and crannies of her body. She doesn’t flinch as the insect probes her lips, explores her pubic hair or perches on a nipple cleaning itself. Seen in extreme close-up, her body and face become a landscape over which the insect is free to roam and unwittingly violate her private space, yet she remains resolutely calm.

There’s a room dedicated to the LPs produced by Ono and Lennon as the Plastic Ono Band, which range from sweetly sentimental to the proto Punk sounds of Ono improvising over pounding backing tracks with the kind of vocals she’d explored when performing with John Cage.

But then something extraordinary happens. The exhibition leaps forward 20 years to 2001, as though when Lennon was shot dead in1980, Ono’s output came to a shuddering halt. In fact, she released an album the following year and continued to produce a flow of records with increasing success until, in April 2003, a remix of her Walking on Thin Ice went to no.1 in the dance charts. She also began collaborating with her son Sean and, in 2009, they set up the Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band. But none of this amazing productivity is mentioned in the exhibition.

In the 1980s, she also began producing bronze editions of earlier sculptures such as the apple, but none of these is on display. So having taken great pains to establish Ono’s credentials as an internationally known artist before she met Lennon, the show then perpetuates the myth that she was dependent on him for inspiration. And the many years since Lennon's death are represented by only a handful of works.

A rowing boat lies stranded at the centre of a room titled Add colour (Refugee Boat). On my visit, the boat and surrounding space were pure white, but a bunch of blue marker pens lay ready for punters to use so, by now, the boat, walls and floor are doubtless festooned with observations about those who take to the seas in desperation and the state of our in world, in general.

Anyone longing for better times can also write a wish on a tag and hang it on one of the Wish Trees stationed at the entrance to the exhibition. For nearly 30 years now, Ono has invited visitors to contribute to these collective expressions of desire and, given their popularity, it seems they answer a need rather like the votive offerings hung in churches by believers.

Anyone longing for better times can also write a wish on a tag and hang it on one of the Wish Trees stationed at the entrance to the exhibition. For nearly 30 years now, Ono has invited visitors to contribute to these collective expressions of desire and, given their popularity, it seems they answer a need rather like the votive offerings hung in churches by believers.

The exhibition closes with a film of Yoko Ono performing Whisper at the Sydney Opera House in 2013. Among the panting, sighing, gasping, crooning, warbling, yelling and whispering are the words “I wish, let me wish” . They’re not really audible, but it doesn’t matter because Ono’s restless creativity has mostly taken the form of a query or invitation, rather than an example. It’s a beautiful way to end the show – with sounds made in her eighties that echo the vocals she was exploring in her twenties.

- Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind is at Tate Modern until 1st September

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment