The Most Precious of Goods, Marylebone Theatre review - old-fashioned storytelling of an all-too relevant tale | reviews, news & interviews

The Most Precious of Goods, Marylebone Theatre review - old-fashioned storytelling of an all-too relevant tale

The Most Precious of Goods, Marylebone Theatre review - old-fashioned storytelling of an all-too relevant tale

An account of one family's near-destruction in the Holocaust given added strength by an uncluttered staging

As last week’s news evidenced, genocide never really goes out of fashion. So it’s only right and proper that art continues to address the hideous concept and, while nothing, not even Primo Levi’s shattering If This Is a Man, can capture the scale of the depravity of the camps, it is important that the warning from history is regularly proclaimed anew – and heeded.

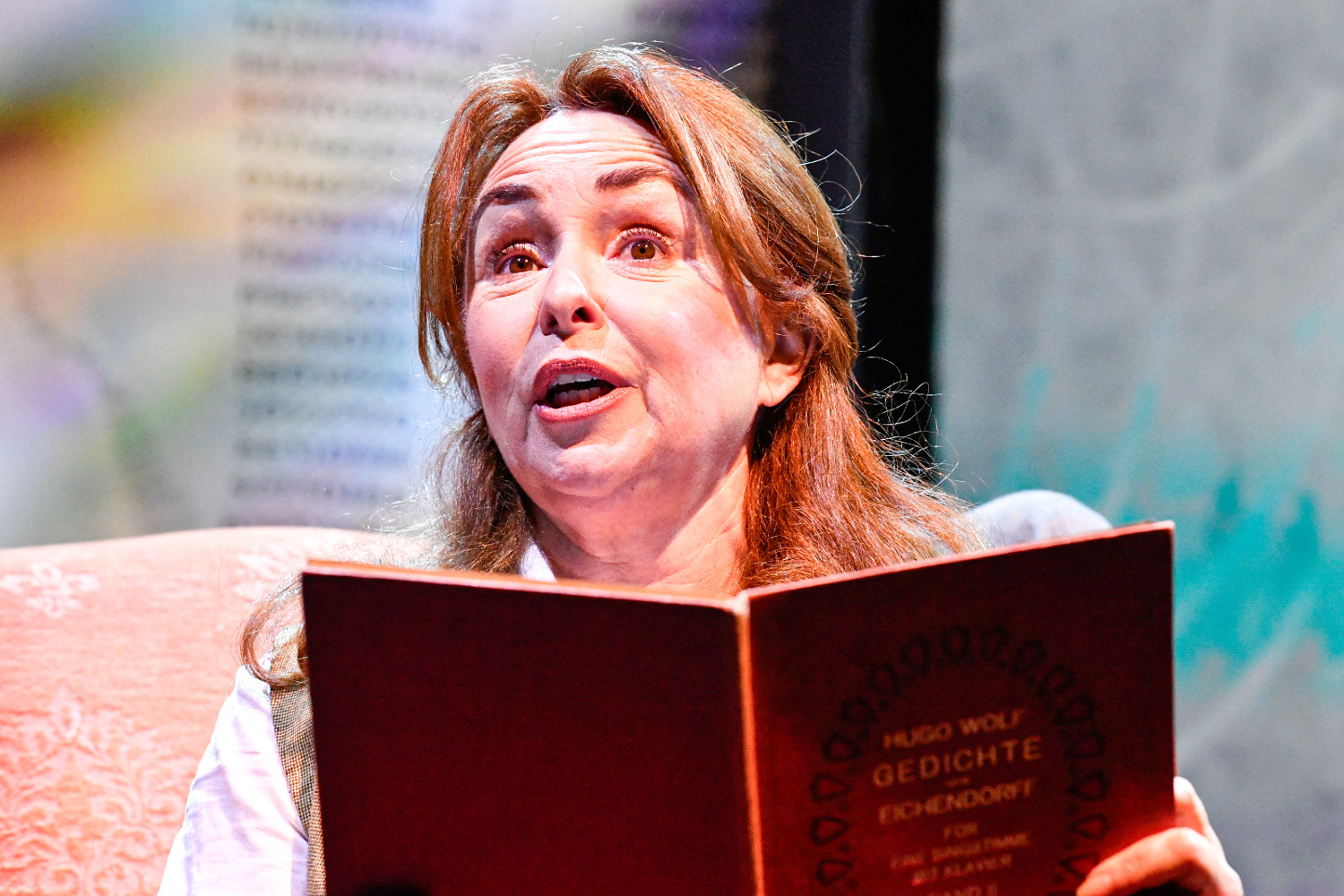

With just a few bleak, snowy back-projections of Silesia’s woodland near Auschwitz (it was enough to chill my soul with memories of a visit 34 years ago) and a lone cellist (Gemma Rosefield) to accompany her on stage, Samantha Spiro (pictured below) reads us a story. It’s more Grimm than grim to begin with, but soon the fairytale morphs into a nightmare. The shadow of the trains, rolling over straight, unbombed railway lines with their cargo of “goods”, falls across the narrative and we know where we are. Soon to be released as a major animated movie, Jean-Claude Grumberg’s novel draws on his family history of transportation to the death camps. There’s a slightly uncomfortable coda that complicates the “truth” of everything we heard, but it’s really just an underlining that the specific story is less important than its standing as an exemplar, not just for the millions of victims of the Holocaust. It also leaves us with the triumph of love that underpins the show’s bittersweet conclusion.

Soon to be released as a major animated movie, Jean-Claude Grumberg’s novel draws on his family history of transportation to the death camps. There’s a slightly uncomfortable coda that complicates the “truth” of everything we heard, but it’s really just an underlining that the specific story is less important than its standing as an exemplar, not just for the millions of victims of the Holocaust. It also leaves us with the triumph of love that underpins the show’s bittersweet conclusion.

Twins are born in France, but their parents are rounded up and packed on to one of those terrible trains to take them to near-certain extermination. The mother can suckle only one baby, so the father takes the heartbreaking decision to throw the girl, wrapped in his prayer shawl, through the bars of the cattle truck’s window into the snow, towards a woman who is the kid’s only, slim hope.

The father survives through a combination of his job as a shaver of heads, but mostly iron will and dumb luck, and the baby survives through the love of the woman and the two men who, eventually, find compassion in their hearts. We guess that these three, against all odds, will meet when the slaughter abates – and they do – but we cannot guess the outcome of that encounter.

Samantha Spiro’s reading brings the text to life with the minimum of different accents and visual characterisation (I was reminded of a low key episode of the BBC’s long-running children’s programme, Jackanory). Crucially, she largely lets the words speak for themselves. That’s a wise decision by director, Nicolas Kent, who also translated the work. There’s plenty enough to grip the house in the unfolding tale, but the unfussy baldness of the staging creates the sense of a testament, a witness statement, a window on unknowable distress and fear.

Don’t take my word for this sparse production's power to compel one's full attention. I saw a matinee attended by 50 or more kids aged about 14, all in uniform, all excited at the prospect of an afternoon out of school. "They're going to spoil it for everyone, scrolling through Insta and wriggling about," I thought to myself, as the lights went down on the 80 minutes all-through reading. But I was wrong.

- The Most Precious of Goods at Marylebone Theatre until 3 February

- More theatre reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

Add comment