Pelléas et Mélisande, Welsh National Opera | reviews, news & interviews

Pelléas et Mélisande, Welsh National Opera

Pelléas et Mélisande, Welsh National Opera

Debussy's masterpiece finds a brilliant production that he would have approved

Debussy completed only one opera (though he started plenty), but it’s the most perfect work imaginable, not only in sheer musical refinement and narrative precision, but in psychological penetration and above all in that exact grasp of the irrational nature of the medium that distinguishes the greatest operas from the merely effective.

I hardly know where to begin in praising this production. But let’s start with the music. Pelléas is an 1890s work, composed in the shadow of Wagner (especially Parsifal but also Tristan), but also under the influence of the French symbolist poets Baudelaire and Verlaine, and, through them, Edgar Allan Poe. The music has a decidedly un-Wagnerian delicacy – even if, as I think, Wagner is underrated in this respect. But because Debussy concentrates an intense symbolic feeling into succinct, elliptical figures, the music calls for a kind of accuracy of timing and colouring that is perhaps less necessary in Wagner’s sweeping paragraphs.

Koenigs is superb at feeling this togetherness of the voice and the orchestraFrom the very start, Lothar Koenigs (also a great Wagnerian) hits this target of locating every detail in musical space, not just in the supremely atmospheric prelude (taken quite slowly), but throughout the early scenes, where Debussy is busy defining the apparently incoherent universe in which these helpless characters battle with, or mostly submit to, their destiny.

I’ve rarely heard orchestral playing of such angelic perfection, such faultless balance and timing. Debussy took from Wagner the idea of the orchestra carrying the drama, but from Musorgsky the concept of the word setting as an ideal conversation; and he brought the two together. Koenigs is superb at feeling this togetherness of the voice and the orchestra; and, in this deceptively tricky music, there is no trace of unease or disagreement between the stage and the pit. One might be listening to the work as Debussy heard it in his head. I can’t think of any higher praise.

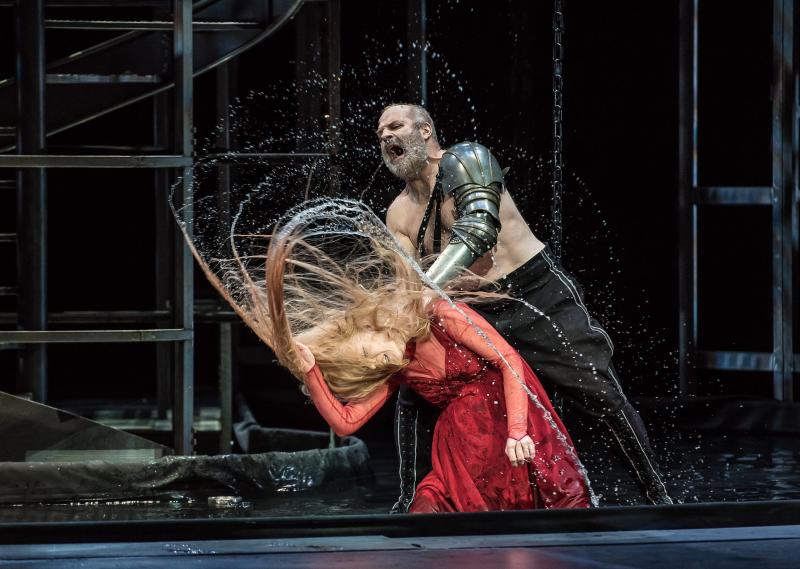

The cast is on this level. The Mélisande, Jurgita Adamonyte (pictured right with Jacques Imbrailo), got the biggest applause, and she is indeed exquisite, with the right French timbre, slightly edgy, a light top, but reserves of warmth as well. But Jacques Imbrailo, as Pelléas, is as good, managing a proper bariton Martin – a light, high baritone, Debussy’s own voice, we’re told – and a marvellous vocal portrait of fragile, astonished passion, a passion that rescues a weak personage from insignificance.

The cast is on this level. The Mélisande, Jurgita Adamonyte (pictured right with Jacques Imbrailo), got the biggest applause, and she is indeed exquisite, with the right French timbre, slightly edgy, a light top, but reserves of warmth as well. But Jacques Imbrailo, as Pelléas, is as good, managing a proper bariton Martin – a light, high baritone, Debussy’s own voice, we’re told – and a marvellous vocal portrait of fragile, astonished passion, a passion that rescues a weak personage from insignificance.

The heavier baritone of Pelléas’s half-brother Golaud is finely taken by Christopher Purves, capturing with horrible conviction the violent bewilderment of a good but unsubtle man confronted, like Wagner’s King Mark, with an emotion outside his comprehension. And there is excellent support from Scott Wilde as Arkel, Leah-Marian Jones as Geneviève, and Rebecca Bottone as the boy Yniold – vocally, at least, though she has trouble with the boyishness.

The production uses a modified version of the set originally created by the late Johan Engels for the company’s Lulu in 2013: a huge metal lattice-work that doubles well enough as a dark forest or the mysterious depths of an ancient castle, but mostly stands for the mental disorder of its inhabitants, not to mention their curiously misaligned relationships – as if half-brotherhood and step-motherhood were a recipe for psychological confusion, as perhaps they are.

The effect of the stage picture is transformed by the lighting designer Mark Jonathan’s brilliant polyphony of darkness and light, and by Marie-Jeanne Lecca’s elegant, stylish pre-Raphaelite costumes, whites and sombre greys and browns in the first three acts, then exploding into bright red as the passion is unleashed in Act 4. The symbolic water that pervades the play, with its wells and fountains and all-embracing sea, has invaded the old set and soaks everyone’s feet and, in her violent scene with Golaud, Mélisande’s hair (main picture).

The key issue, though, is the intense musicality and psychological grasp of Pountney’s handling of the drama itself. There are fine individual touches at every point, but what counts above all is a certain understatement of movement that exactly reflects the tone and pace of this most discreet of all operatic scores. Watching Mélisande failing to relate to Golaud in the first scene, or her sudden radiance in Pellèas’s presence, is like watching the music unfold. As these characters float round each other or pick their laborious way through, or up and down, the lattice-work, one remembers Debussy’s fury at Nijinsky’s staging of Jeux which, he told a friend, “glared at the music as it went past”. This new Pelléas caresses the music, and I think Debussy would have loved it.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Comments

I'm afraid I disagree - I