The Fabulist, Charing Cross Theatre review - fine singing cannot rescue an incoherent production | reviews, news & interviews

The Fabulist, Charing Cross Theatre review - fine singing cannot rescue an incoherent production

The Fabulist, Charing Cross Theatre review - fine singing cannot rescue an incoherent production

Beautiful music, but curious decisions in scripting and staging sink the show

On opening night, there’s always a little tension in the air. Tech rehearsals and previews can only go so far – this is the moment when an audience, some wielding pens like scalpels, sit in judgement. Having attended thousands on the critics’ side of the fourth wall, I can tell you that there’s plenty of crackling expectation and a touch of fear in the stalls, too. None more so than when the show is billed as a new musical.

By the interval (much before that if it’s a hit), you’re locating the production on a multi-dimensional spectrum, assessing its component parts (acting, plot, design), its impact on those around you and its position within the culture of theatre and the wider society it reflects. You’re also keen to find out how it’s all going to be resolved in the third act.

After well over 1,000 or so reviews, this process is as automatic as showing one’s ticket and shuffling to one’s seat. But it wasn’t happening with The Fabulist, James P Farwell’s updating of Giovanni Paisiello’s 1779 operetta, The Imaginary Astrologer, now set in Mussolini’s Italy. Part musical theatre, part opera, part pantomime, part magic show, part political satire, part old-school comedy, there’s plenty of Mozart at his most madcap in the inspiration and even a bit of Shakespeare with his penchant for slippery identities. But what really came to mind was Homer’s Car, a set of individual ideas bolted together to form an ugly vehicle.  Amidst so much being thrown at the wall to see what sticks, there will be elements that work well. The music, easy on the ear, free of bombast, is beautifully played by Samuel Woolf’s five-strong, highly accomplished orchestra. That said, we should hear more of it, opera’s unique power to tell a story as much through the cadences and moods of the music as the libretto, continually interrupted by slabs of somewhat stilted dialogue and pedestrian character development that seldom goes beyond caricature.

Amidst so much being thrown at the wall to see what sticks, there will be elements that work well. The music, easy on the ear, free of bombast, is beautifully played by Samuel Woolf’s five-strong, highly accomplished orchestra. That said, we should hear more of it, opera’s unique power to tell a story as much through the cadences and moods of the music as the libretto, continually interrupted by slabs of somewhat stilted dialogue and pedestrian character development that seldom goes beyond caricature.

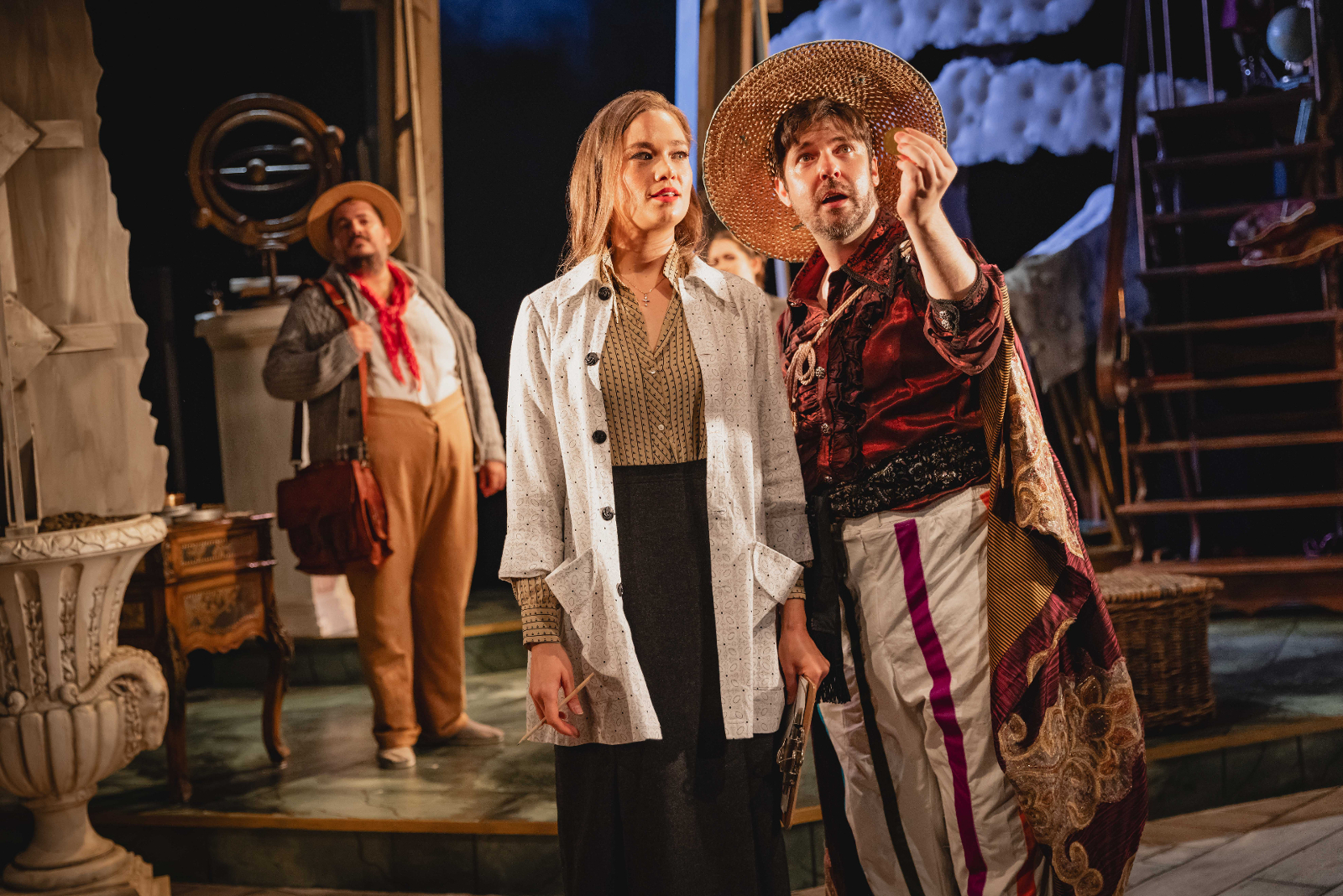

The cast sing beautifully and act their socks off with this thin material. Hungarian soprano, Réka Jónás (pictured above, with Dan Smith and Constantine Andonikou), makes good use of her crystal clear voice as the screenwriter/man-eater Clarice, who has the cojones to stand up to her father, the church and Il Duce. Her sister, Cassandra, suited like Marlene Dietrich and directing movies like a liberal Leni Reifenstahl, is given plenty of agency by Lily de la Haye in the first half, but is underwritten to the point of near invisibility in the second. Why the younger sister has a strong American accent and the elder a posh English voice is never explained.

Dan Smith as the eponymous magician hero, Agrofontido, may not possess the singing chops of the rest of the cast, but he pulls off a terrifying array of magic tricks (designed by Harry de Cruz) any of which could go wrong and stall the show. Indeed director, John Walton, manages a very busy set and dizzying volume of props with no little skill, but it would be impossible to avoid the distractions so caused. Constantine Andonikou dials up the camp and veers closer to panto than anyone as the erudite comical sidekick Pupuppini, but he has to stand and observe from the edge of the stage for far too long.

Quite how the two boys snare the feisty writer who has rejected scores of would-be beaus and the powerful moviemaker who has sworn off men for life, isn’t clear – the pairing off at the end seems almost expedient, as something has to bring down the curtain. Surely more chemistry, more spark needs to be demonstrated earlier to convince us that these two women would fall for these two men?

Rounding out the cast, James Paterson channels Caractacus Pott as the girls’ eccentric inventor father, Count Petronius, and Stuart Pendred goes full Rodrigo Borgia as a sadistic, hypocritical cardinal happy to do fascism’s work in rounding up radicals, heretics and magicians for re-education.

As the tone veers from slapstick to dark satire, the action breaks for an extended discussion of the relationship between the seen rational world and its unseen magical counterpart which, jarringly, had echoes of Albert Einstein and Max Planck's discussion of the realms of relativity and quantum mechanics – an irritatingly long set of bird screeches may be an in-joke referencing this allusion. There’s also another break for a floating orb routine, impressive if you’re seeing it for the first time.

Perhaps the writer himself gives the best summation of the show when he writes in the programme that he wrote it to entertain his friends and family. That’s fine, but it’s probably not enough to warrant a six-week run in the West End at £40 or so a pop.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment