Directors the Dardenne brothers: 'To be living means to be fragile' | reviews, news & interviews

Directors the Dardenne brothers: 'To be living means to be fragile'

Directors the Dardenne brothers: 'To be living means to be fragile'

The Belgian masters discuss 'Tori and Lokita', and finding humanity on film

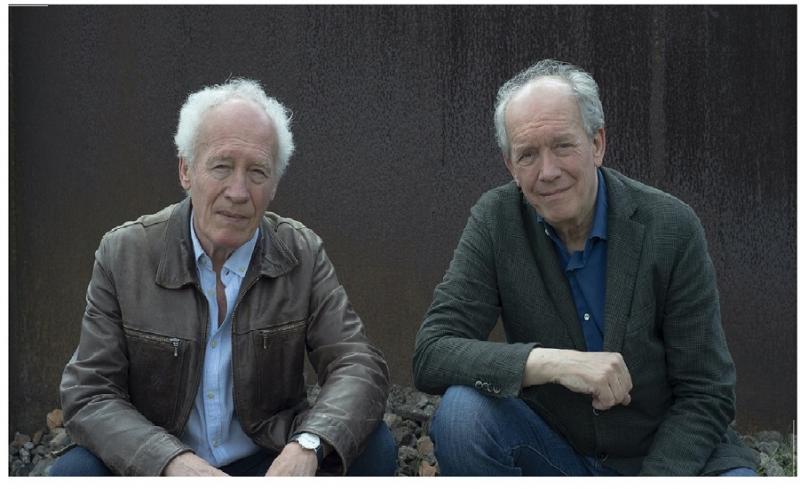

Belgian brothers Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne have made their home region of Liège the site of excruciating moral crises and crushing injustice. Their 12 masterful, double Palme d'Or-winning films act as parables for the embattled human soul.

The latest, Tori and Lokita, sees two paperless child migrants, 12-year-old Tori (Pablo Schils) and 16-year-old Lokita (Joely Mbundu), form a familial bond in the face of ruthless criminals and oppressive bureaucracy. There is furious energy as Tori pumps his bike down neon city streets on a drugs run, and stygian despair when Lokita is walled away in a marijuana plantation.

The brothers began as documentarians, and intense, months-long rehearsals, precisely calibrating the duration of movements and shots, maintain an illusion of naturalism. As they noted at a London Film Festival screening at the Curzon Mayfair, though, Tori and Lokita is also a film noir and adventure film. The brothers exert an icy grip, more Hitchcock than Ken Loach.

Despite sometimes unflinching narratives, Dardennes films aren’t grim. If they stand in Robert Bresson’s austerely realist tradition, they also share his spiritual profundity. There is a loving optimism in their protagonists’ courageousness, and firm faith in right and wrong. In The Unknown Girl (2016), for instance, Adèle Haenel’s doctor, pictured above right, is haunted by a migrant woman killed after she was turned away from her surgery. She becomes a nemesis, needing to name victim and killer. The Dardennes’ heartfelt tales of abused migrants, often fused with deep empathy with children, start with their first success, La Promesse (1996).

Despite sometimes unflinching narratives, Dardennes films aren’t grim. If they stand in Robert Bresson’s austerely realist tradition, they also share his spiritual profundity. There is a loving optimism in their protagonists’ courageousness, and firm faith in right and wrong. In The Unknown Girl (2016), for instance, Adèle Haenel’s doctor, pictured above right, is haunted by a migrant woman killed after she was turned away from her surgery. She becomes a nemesis, needing to name victim and killer. The Dardennes’ heartfelt tales of abused migrants, often fused with deep empathy with children, start with their first success, La Promesse (1996).

Since the Cannes Grand Prix-winning The Girl With a Bike (2011), formal and aesthetic beauty also poignantly contrasts with characters’ travails. When Sandra (Marion Cotillard) spends a weekend begging her co-workers to vote to forgo a bonus to save her job in Two Days, One Night (2014), bright blue sky and birdsong illuminate this capitalist scapegoat’s misery.

The Dardennes meet theartsdesk the day after that Mayfair screening, in a nearby hotel. Jean-Pierre, 71, is quieter, more reflective. Luc, 68, is punchy, with an ironic edge. They laugh easily, happy in the enduring rhythm of each other’s company, and their finely crafted art.

NICK HASTED: This film is lit up by the love between these two children. The cliché would have been to define them by the misery of their circumstances, but instead you define them by their friendship. Was that the heart of the film you wanted to make?

JEAN-PIERRE DARDENNE: It what we chose to do. From the moment we decided to focus on their friendship, it was the idea to not get stuck with the details of the reality. The friendship is what gives a structure to the film. The friendship is what fights against the terrible things they’re experiencing, and it’s what makes us need to get them back together when they are separated, for example when Lokita is at the cannabis plantation. They have to find a way, and that’s how it structures the film.

Even when they’re almost powerless, they still have their love’s solidarity.

J-P: That’s what we wanted really, that the term you use, solidarity, would be undented – infallible.

LUC DARDENNE: The friendship would be indestructible, and remain there at the heart, because it could have been a story of betrayal. For example, when Tori got involved with drugs, he could have left with [gangster] Betim and not gone to save Lokita. But no. We really wanted at its heart this friendship to be unbreakable.

J-P: There’s also a question of morals and immorality within friendship. Because friendship will make you do certain acts that maybe you would choose not to do. And she chooses in the end to give a lot. Had characters in these sorts of circumstances been on your minds for a while? Because the young migrant who is murdered in The Unknown Girl could be Lokita a few years later.

Had characters in these sorts of circumstances been on your minds for a while? Because the young migrant who is murdered in The Unknown Girl could be Lokita a few years later.

J-P: Yes, it could be. And this time, they are the main characters of our film. Ten years ago, we had started working on a script that wasn’t made – which was based around a family from Cameroon, a mother and two children coming into Belgium, but the mother gets caught by the police and is deported. The kids manage to escape, and she had told them: “Go to the police, tell them you’re unaccompanied minors, and whatever you do, stay together. Do not leave one another, that’s the only way – otherwise you will not survive.” So I guess yes, there is a thread.

You said last night, Jean-Pierre, that there is an accusation in this film, that hasn’t been present so clearly in previous films. Where does that accusation point? What do these characters, Lokita and Tori, demand of us?

J-P: I said it last night, but we both think it. The last words of Tori are: “If Lokita had had her papers…” So even if there are traffickers, smugglers, gangsters, the basic fact is, there’s Lokita – and if she had had her papers, all this wouldn’t have happened. They don’t have a crazy dream, it’s just a very normal dream. She wants to be able to work as a home-help, he wants to go to school, and they want to have a little home, a flat, to live in together. That’s all!

Is there an anger behind this film?

L: Yes. We made it because we read articles about the fact that so many unaccompanied minors disappeared. And not just because they tried to leave Belgium for England, or were sent back – they disappeared in abnormal circumstances. They go underground in a criminal world – and that is not normal, and not acceptable. In Two Days, One Night, the husband says to Sandra [Marion Cotillard, pictured above]: “You exist, Sandra.” And in the film, she learns to remember that. Is one of the crimes you show in this film that we have stopped seeing that children like Tori and Lokita exist? That they don’t have an important reality, so they can be ignored and disposed of?

In Two Days, One Night, the husband says to Sandra [Marion Cotillard, pictured above]: “You exist, Sandra.” And in the film, she learns to remember that. Is one of the crimes you show in this film that we have stopped seeing that children like Tori and Lokita exist? That they don’t have an important reality, so they can be ignored and disposed of?

L: Yes, that’s true. They don’t exist. We don’t want to see them, and we don’t see them.

J-P: That’s what they tell each other all the time – to help each other. To hold each other together, really… when she says, “I wish my mum was here.” And he says, “But I’m here. I’m here to support you, you are here with me, and you exist.” And it works the other way as well.

L: And at the school, he’s made drawings of Lokita – she exists for him, and he’s done this portrait, and I believe it’s friendship that makes Lokita exist.

And perhaps the importance of this film for the viewer is that these characters fully exist in the film – you can’t steer round them. They’re alive.

L: That’s our job! [laughs] And the film is also in a way an act of resistance, by giving something other than the reality. To be able to make both Tori and Lokita exist as living, human beings.

You’ve spoken about the long rehearsal process in all your films, to make the characters fully present. I know it’s work, craft – but making those characters real, bringing them to life in front of the camera, sounds almost magical.

L: It’s about finding all those details – a voice, a way of movement, your hat, accessories, costumes – that give an existence to a character. And it’s important that it’s not just a general image – they’re not just an impersonal file, a social case, an unaccompanied minor. That’s why we work on details. It takes a lot of time. And some details were in the script, but that’s what we find through a lot of work – whether it’s how to walk, or what to do with a leg, of when Tori holds out a little list to make Lokita rehearse what she has to say. For example, you might remember the little shoulder-bag where they put the drugs. Lokita gives him help to climb into the hole, and says, “Wait, give me your bag.” Then she passes the bag back, and he says, “I’ll text you when all is good,” and then, pff, closes the hole. And then suddenly you really feel Lokita’s loneliness. They found all those things in rehearsal.

L: Our cinema’s not very spectacular, and we try to use the sets, the props, and very few elements, and I think that’s why it works to give a life to the characters. If there was too much stuff, you’d be drowned in it. Of all of the marginalised and pressurised characters that you have wanted to show in your films, are these exiled children the ultimate expression of that – the least powerful, and most put-upon?

Of all of the marginalised and pressurised characters that you have wanted to show in your films, are these exiled children the ultimate expression of that – the least powerful, and most put-upon?

J-P: Maybe! [laughs]

L: It’s not the old-fashioned type of slavery, but it is a very modern type who make them work. The two children are disposable. We know that if something happens, nobody’s going to complain or ask about it. So they make them work, and they have this relationship where [the slavers] can be quite friendly as well – but you know that ultimately they do what they want with them.

J-P: And to come back to the idea of anger, it is incredible, and totally unjust that in our society, a democracy where we are all citizens with rights, there are individuals who are minors who can just disappear – like that.

Has the society in which your films exist gotten worse in the time you’ve been making them? Do the pressures and the injustices that your characters experience squeeze more?

J-P: You have to be careful when you say things go from bad to worse. There weren’t so many unaccompanied children coming from sub-Saharan Africa, Vietnam or Afghanistan before. It must be a reflection that shows a huge despair over there, and massive hope in coming here. For a mother to want her child to leave, and demand of her to work and send money, a bit like when a mother abandons her child – the life situation is so harsh, it makes her do that.

It’s true that your films aren’t spectacular, and they get called naturalistic, but of course they’re very far from documentary. Are the stories in which you frame your characters often moral tales – parables?

J-P: Yes. There’s often a link with death, and whether you will leave a person to die or not, whether you will participate in another person's death or not. Here it’s a bit different, because the two characters are linked by friendship. Are you going to be put your life before the other’s, or not?

L: And here this friendship is so indestructible and infallible that we thought in that way that they won’t hesitate to protect each other.

J-P: We said that their real place of refuge, their real homeland, is their friendship. You don’t just make gritty, realistic, documentary-like films. There is a visual beauty in all of them. Is that just part of what your camera sees?

You don’t just make gritty, realistic, documentary-like films. There is a visual beauty in all of them. Is that just part of what your camera sees?

BOTH: Thank you! We try!

J-P: I think in the case of this film, it was because we really obsessed with wanting Tori and Lokita to be living beings. What guides us is that to be living means to be fragile. There are two examples in this film, two things that escaped us a bit as directors with these characters. When Lokita is with [captor] Margot in the marijuana plantation, she asks her to help her contact her brother, and Margot says, “No, no, just put your frozen food away or they’ll thaw.” And she had actions she was supposed to do, but it’s the way she comes back. We’re not on her, it’s just her back, and when she carefully puts the food away and then she’s alone, you feel the total solitude, just with her back, and the delicate action of putting away the food. She’s talking to her brother by doing that.

L: So this is where it escapes us, and it just happens on the screen when we’re filming, that we’ve captured a shot of a human being. And the second example is where Tori is hiding in the car and Betim goes into the hanger, and Tori climbs out and he’s against the wall, waiting to find out if Betim is going out – and suddenly he’s there crouching, and there are stones there, and we both had a moment where this is an image where he’s a child, but he’s already an old man. It’s the whole history of Africa in that moment of loneliness, crouched there. And that’s when you realise we are filming a human being.

Do you see much of each other when you’re not filmmaking? Or is filmmaking part of your family relationship as brothers?

J-P: We have a company together as well. So we have discussions about things we believe are important. But also futile! And the gossip [chortling together] and news items we may have read. That’s what we’re interested in when we read news items or information, if such a person did or said that. Those beautiful signs of characters.

- Tori and Lokita is exclusively in cinemas now

- More film reviews on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

Comments

Really excellent interview -