Three Kings, Old Vic: In Camera review - Andrew Scott vividly evokes generational pain | reviews, news & interviews

Three Kings, Old Vic: In Camera review - Andrew Scott vividly evokes generational pain

Three Kings, Old Vic: In Camera review - Andrew Scott vividly evokes generational pain

This new livestreamed monologue explores family and the burden of inheritance

The world premiere of Stephen Beresford’s new hourlong play, livestreamed to home audiences in four performances as part of the Old Vic’s In Camera series, was postponed a couple of times due to Andrew Scott undergoing minor surgery.

Beresford’s play centres on the fraught relationship between Patrick and his absentee father. They first meet when the former is an awed, frightened eight-year-old, admiring this stranger’s flamboyant dress, stylish smoking and expansive tales involving foreign adventures, bar etiquette, and their grand Spanish ancestry. However, any hope that this is the start of an intimate relationship is swiftly dashed; with cavalier cruelty, his father says he’ll only come back to see him if young Patrick can solve a coin trick dubbed the Three Kings. It’s another eight years before they speak again.

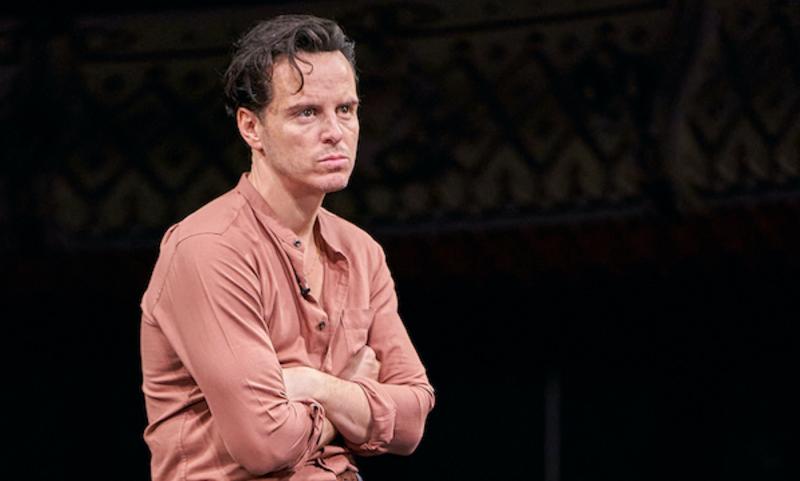

Scott (pictured below) evokes both characters with pin-sharp precision, as well as several others: Patrick’s vain, fragile, pill-popping mother, who disparages his father just as he does her; his older sister, who recalls them fleeing from debt collectors in Dublin; his father’s friend Dennis, awkward conveyer of yet more hurtful revelations; and his younger half-brother, also called Patrick, innocent and pathetically grateful for a shred of fraternal affection.

Beresford’s incisive script constantly shows the agonising gulf between expectation and reality. “Men who love their families – I have an antenna for it,” says Patrick, and he knows that his father is not one of them. More heartbreaking: he admits that he isn’t such a man either; just like his father, he too is deceitful, a drinker, an irresponsible charmer, emotionally unavailable. That inheritance of sin is the devastating runner. The coin trick becomes a prophecy – “the force of one ricochets through the other two” – and as much as Patrick loathes his father, his self-loathing is almost more powerful.

Beresford’s incisive script constantly shows the agonising gulf between expectation and reality. “Men who love their families – I have an antenna for it,” says Patrick, and he knows that his father is not one of them. More heartbreaking: he admits that he isn’t such a man either; just like his father, he too is deceitful, a drinker, an irresponsible charmer, emotionally unavailable. That inheritance of sin is the devastating runner. The coin trick becomes a prophecy – “the force of one ricochets through the other two” – and as much as Patrick loathes his father, his self-loathing is almost more powerful.

We could certainly analyse the wider implications of that idea, while we, as a society, become increasingly aware of the importance of collective responsibility, and how the actions of one generation shape the next. But this is primarily an intimate character study, teeming with vivid descriptions. Patrick’s father comes more into focus with each detail: his daughter wryly recalls “he could only flourish in Georgian architecture”; we hear his distinct, sometimes amusing turn of phrase, as when he describes French as “a series of vocalised evasions”; there’s his troubles with the law, the compulsive womanising, the dodgy business ventures of the unrepentant chancer. Later, suffering from cancer, he’s also a conspiracy theorist railing against Big Pharma – but, at night, gripped by terror.

Partly by necessity for this scratch performance, Matthew Warchus’s direction is unfussy, but that suits the piece well. One major creative choice is very effective: a split screen, showing us Scott’s performance from different angles. That helps us imagine the dialogues between several people, as well as giving us both his body language and an immersive close-up. It’s riveting during key moments, like when Patrick’s drunken father reveals he’s remarried and had another boy, “the longed-for son and heir”. Scott somehow divides in two: the nasty drunk spitting this information down the phone, and the son absorbing it like a body blow. We also see a division, as when Patrick recalls vile email exchanges between them while, in the present, caring for his sick father – one hand reaching out to comfort him. Yet the monologue form means he is, ultimately, alone.

The use of sound effects helps summon different locations, including salsa music and chirruping cicadas. But the main focus is on this gifted storyteller, and Beresford’s piece is beautifully crafted for Scott’s range, giving him moments of fury, partly masked by biting humour and studied nonchalance, of raw pain (including a roar from the father like that of a dying animal), and of physical comedy – like an elaborate bow Patrick attempts while soused. There’s also an emerging examination of faith. Patrick uses the word “faithless” in multiple senses; this is a string of men who abandon their families, but who also feel untethered from a guiding power. A final plea for mercy is naked and humbling: that forgiveness which is not deserved, or earned, but can still be bestowed – perhaps to break a cycle and free the next generation.

- Three Kings was livestreamed by the Old Vic on 3-5 September

- Read more theatre reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Nye, National Theatre review - Michael Sheen's full-blooded Bevan returns to the Olivier

Revisiting Tim Price's dream-set account of the founder of the health service

Nye, National Theatre review - Michael Sheen's full-blooded Bevan returns to the Olivier

Revisiting Tim Price's dream-set account of the founder of the health service

Girl From The North Country, Old Vic review - Dylan's songs fail to lift the mood

Fragmented, cliched story rescued by tremendous acting, singing and music

Girl From The North Country, Old Vic review - Dylan's songs fail to lift the mood

Fragmented, cliched story rescued by tremendous acting, singing and music

The Merry Wives of Windsor, Shakespeare's Globe review - hedonistic fizz for a summer's evening

Emma Pallant and Katherine Pearce are formidable opponents to Falstaff's buffoonery

The Merry Wives of Windsor, Shakespeare's Globe review - hedonistic fizz for a summer's evening

Emma Pallant and Katherine Pearce are formidable opponents to Falstaff's buffoonery

Run Sister Run, Arcola Theatre review - emphatic emotions, overwrought production

Chloë Moss’s latest play about the different lives of two sisters is deeply felt

Run Sister Run, Arcola Theatre review - emphatic emotions, overwrought production

Chloë Moss’s latest play about the different lives of two sisters is deeply felt

Intimate Apparel, Donmar Warehouse review - stirring story of Black survival in 1905 New York

An early Lynn Nottage work gets a superb cast and production

Intimate Apparel, Donmar Warehouse review - stirring story of Black survival in 1905 New York

An early Lynn Nottage work gets a superb cast and production

Hercules, Theatre Royal Drury Lane review - new Disney stage musical is no 'Lion King'

Big West End crowdpleaser lacks punch and poignancy with join-the-dots plotting and cookie-cutter characters

Hercules, Theatre Royal Drury Lane review - new Disney stage musical is no 'Lion King'

Big West End crowdpleaser lacks punch and poignancy with join-the-dots plotting and cookie-cutter characters

Showmanism, Hampstead Theatre review - lip-synced investigation of words, theatricality and performance

Technically accomplished production with Dickie Beau never settles into a coherent whole

Showmanism, Hampstead Theatre review - lip-synced investigation of words, theatricality and performance

Technically accomplished production with Dickie Beau never settles into a coherent whole

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review - powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review - powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

Joyceana around Bloomsday, Dublin review - flawless adaptations of great dramatic writing

Chapters and scenes from 'Ulysses', 'Dubliners' and a children’s story vividly done

Joyceana around Bloomsday, Dublin review - flawless adaptations of great dramatic writing

Chapters and scenes from 'Ulysses', 'Dubliners' and a children’s story vividly done

Stereophonic, Duke of York's Theatre review - rich slice of creative life delivered by a 1970s rock band

David Adjmi's clever and compelling hit play gets a crack London cast

Stereophonic, Duke of York's Theatre review - rich slice of creative life delivered by a 1970s rock band

David Adjmi's clever and compelling hit play gets a crack London cast

North by Northwest, Alexandra Palace review - Hitchcock adaptation fails to fly

Emma Rice's storytelling at fault in misconceived production

North by Northwest, Alexandra Palace review - Hitchcock adaptation fails to fly

Emma Rice's storytelling at fault in misconceived production

Add comment