Andreas Gursky, Hayward Gallery review - staggering scale, personal perspective | reviews, news & interviews

Andreas Gursky, Hayward Gallery review - staggering scale, personal perspective

Andreas Gursky, Hayward Gallery review - staggering scale, personal perspective

Space and light at the refurbished Hayward: huge views, artful manipulation from the German photographer

“Let the light in” has been the fundraising slogan for the two-year project to revamp and modernise the Southbank Centre’s Hayward Gallery, and adjacent Queen Elizabeth Hall and Purcell Room. And that is just what has happened, with two triumphs at the Hayward.

The first is the building itself. It has long been a marmite, love it or hate it, sample of fashionable 1960s brutalism: it opened in 1968, followed less than a decade later by the National Theatre and the Barbican, to mention more examples. Yet from the beginning the Hayward, named after a chairman of the London County Council, and designed by LCC architects, has been the home of inspiring exhibitions, brilliantly arranged. Its early history came at a time when major museums in London were just beginning to seriously initiate their own shows, so the Hayward fulfilled a real need across the worldwide spectrum of applied and fine arts, architecture and photography, historic and contemporary. It has been fashionable to malign the building but the galleries proved remarkably adaptable: early outstanding exhibitions included its opening salvo Frescoes from Florence, then Matisse and Picasso’s Picassos (before the Picasso Museum opened in Paris), Lutyens, the Festival of India, to name but few. Most were revelatory. Now the light has been indeed let in with a roster of pyramidical roof lights on the first floor galleries (brilliantly lit at night with varying colours as a new kind of found sculpture), as well as refreshed interiors and configurations of the interior spaces. Optimum visitor conditions and backstage conditions have produced a more pleasing, welcoming, efficient and pleasant Hayward.

Now the light has been indeed let in with a roster of pyramidical roof lights on the first floor galleries (brilliantly lit at night with varying colours as a new kind of found sculpture), as well as refreshed interiors and configurations of the interior spaces. Optimum visitor conditions and backstage conditions have produced a more pleasing, welcoming, efficient and pleasant Hayward.

So this first exhibition is a good match: 68 photographs, from 1984 to 2016, mostly on a huge scale with just a handful of surprisingly small images, by Andreas Gursky from his own collection of his work. Born in 1955, he studied at the fabled Düsseldorf School of Photography, taught by Bernd and Hille Becher, and is now himself a professor there. By his mid-thirties he was internationally shown and acclaimed, by his forties the subject of a Profile in the New Yorker.

Gursky has travelled the world and almost all his imagery is concerned with the human presence

It has become almost a commonplace to paraphrase Picasso’s famous remark that artists lie to tell the truth. Nowhere is this more a crucial observation than when considering the medium of photography, the mechanical reproduction. Subliminally we always believe in photography’s reality. But it has always been teased and manipulated from its earliest history. Gursky makes no secret of this, with his manipulations first in the dark room and, as techniques and technology evolved, with the computer, playing in the creative spaces between the observed and the interpreted. And almost all the hallucinatory imagery he has so often manipulated digitally, and treated in all the kinds of ways now available in the land of technophilia, is precisely focused in mesmerising hypnotic intensity over the entire picture surface. (Pictured above: Les Mées, 2016)

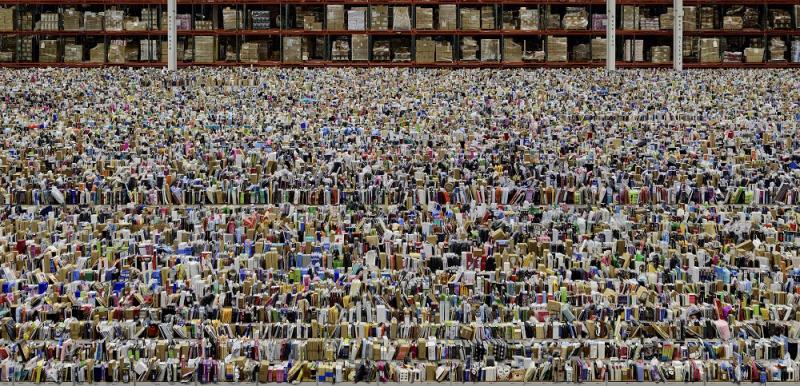

Gursky has travelled the world and almost all his imagery is concerned with the human presence, many as actual people in landscapes both vast and intimate. In the absence of actual human presence, human artefact is depicted in all sorts of ways: an environment of piled-up offerings, the receding wall of cheap consumer goods from a bargain store, 99 Cent; the largest apartment building in Paris, Montparnasse, 1993; Amazon, the huge depot in Arizona, 2016 (main picture).

A quietly startling fiction is that of Review, 2015, in which we see simply the back view of four people sitting in front of Barnett Newman’s 1950s painting, the vast almost incandescent abstraction Vir Heroicus Sublimis. The four, recognisable even from the back, are the four recent German Chancellors, Angela Merkel, Gerhard Schröder, Helmut Kohl and Helmut Schmidt. (The Newman may even recall a famous exhibition of the spiritual in abstract art held at Berlin’s Charlottenburg many years ago.) This curiously potent image also highlights the paradoxical mix of effects that Gursky’s photographs evoke: both inert and lively, deadening and exhilarating in almost equal measure.

And although most of Gursky’s photographs are apparently plot-less, they are exceptionally stimulating in terms of making the viewer think in all sorts of unexpected ways. Here, for instance, are the luminescent display cases of a shop, empty of objects but obviously in its elegant austerity hinting at luxury to come, in Prada II, peculiarly evocative of minimalist sculpture, notably Dan Flavin. Rhine, II (1999, remastered 2015, pictured below) is an utterly flat silvery stripe between two flat grassy banks, the top border an uninflected sky. It is oddly reminiscent of colour field painting. Madonna I, 2001, is a huge aerial crowd scene of a massive pop concert; which tiny figure on the stage, in semi-isolation, is she? Tour de France, 2007, depicts a winding hilly road punctuated by cars and people with a tiny cluster – like a needle in the haystack – of labouring cyclists. There are many real crowd scenes, too: city views, stock exchanges, factories, enormous concatenations of buildings, people, objects and people; and in several landscapes just tiny groups, as in the walkers of the Klausen Pass, 1984, dwarfed by sky, meadows, fields, mountains.

Madonna I, 2001, is a huge aerial crowd scene of a massive pop concert; which tiny figure on the stage, in semi-isolation, is she? Tour de France, 2007, depicts a winding hilly road punctuated by cars and people with a tiny cluster – like a needle in the haystack – of labouring cyclists. There are many real crowd scenes, too: city views, stock exchanges, factories, enormous concatenations of buildings, people, objects and people; and in several landscapes just tiny groups, as in the walkers of the Klausen Pass, 1984, dwarfed by sky, meadows, fields, mountains.

He can even convince us that the totally inanimate is somehow animated, as in a close-up of the pile of a grey carpet, the floor of a public art gallery, in Untitled I, 1993. Turner Collection, 1991, is a view of three wildly romantic landscapes, in flurries of colour, contained in gold frames, hung in a straight line against a white wall, the wooden floor of the gallery below: soaring imagination tamed and shown in orderly fashion.

Manipulating both in the dark room and later with computers, Gursky works always with what he has seen and observed – whether close up or far away, sometimes manipulated by means of collage and montage – to show us what we would otherwise not have noticed. Beyond that he indicates subtly and sometimes forcefully our places in the world – sometimes meaningful, sometimes insignificant; we are dwarfed at times, powerful at others. The quotidian is oddly mysterious, the familiar unfamiliar, and even vice versa: a new minted world, both frightening and beautiful.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment