Darius Battiwalla, Royal Northern College of Music, Manchester review - improvisation extraordinaire | reviews, news & interviews

Darius Battiwalla, Royal Northern College of Music, Manchester review - improvisation extraordinaire

Darius Battiwalla, Royal Northern College of Music, Manchester review - improvisation extraordinaire

Remarkable resources of organ and player bring a classic silent film to life

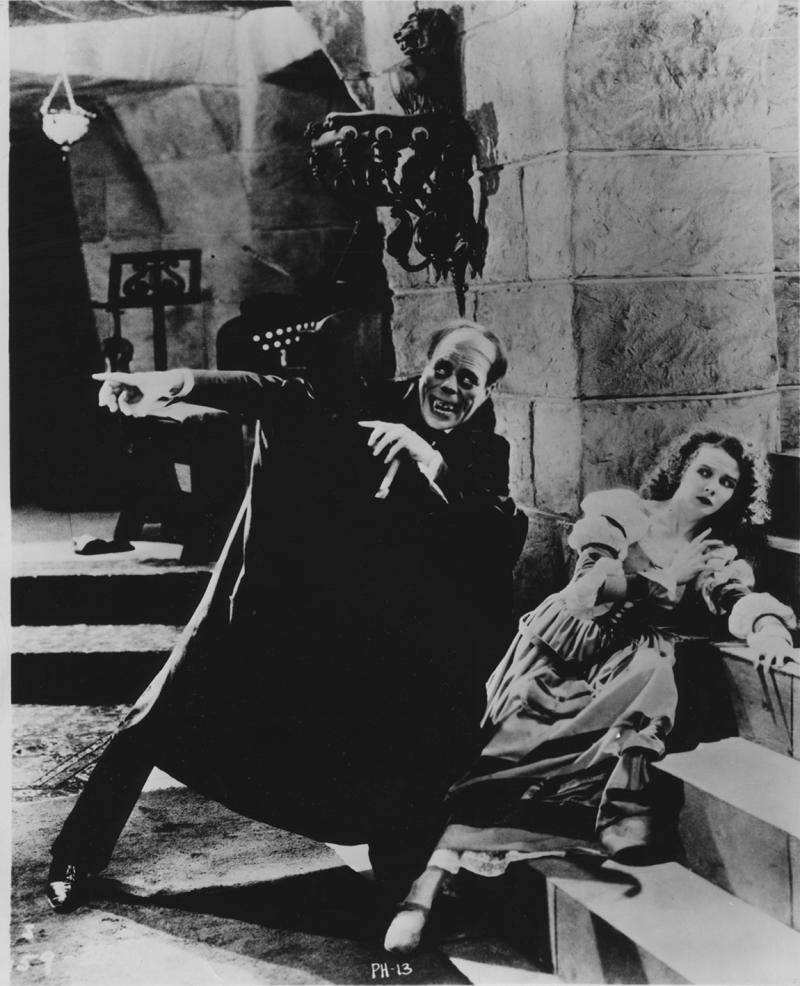

Organ improvisation is a remarkable art, prized in French musical culture particularly, and there was something highly appropriate in the choice of The Phantom of the Opera – a screening of the 1925 silent film with live accompaniment on the RNCM concert hall organ by Darius Battiwalla – as part of the "French Connections" year-long festival at the Manchester conservatoire.

The story is, after all, set in the Paris Opéra, and taken from the 19th century novel by Gaston Leroux. Those who know the Lloyd Webber version will be familiar with the outline of it, but the silent film follows its original with great precision, including frequent references to the Gounod opera, Faust et Marguérite, which is seen in progress in several scenes (providing an extra dimension to the beauty-and-the-beast story of The Phantom, as the disfigured monster seeks redemption from the love of a beautiful woman, which Gounod’s work assures us is so possible).

There must be something about organists and megalomania

Indeed, the music of the Gounod work is there to be imagined, and composer Carl Davis, who has written an orchestral score for the film, is adamant that the scenes from the opera are incorporated in the film in real time, as it were, so that when it cuts away from the on-stage performance scenes and back again, the opera can be seen to have been continuing on stage even when we’re not looking at it. Darius Battiwalla, tutor in organ improvisation at the Royal Northern College of Music and a frequent recitalist in the North and elsewhere, has taken part in performances of Davis’s score to the film, and he agrees with that.

The story is also characterised by the idea that the Phantom is himself an organist – like Dr Phibes, Captain Nemo and many another cinematic evil genius, he has managed to construct a large pipe organ inside his hidden lair and delights in its grandiose sounds. There must be something about organists and megalomania…

But for Battiwalla (pictured left) all this is a challenge, both intellectually and musically. A silent film gains immensely from musical accompaniment of any kind, and this one probably above most from the sound of the organ. He’s done it before, and indeed has improvised to classic silent cinema in other venues, including the National Media Museum in Bradford.

But for Battiwalla (pictured left) all this is a challenge, both intellectually and musically. A silent film gains immensely from musical accompaniment of any kind, and this one probably above most from the sound of the organ. He’s done it before, and indeed has improvised to classic silent cinema in other venues, including the National Media Museum in Bradford.

Playing continuously for 90 minutes would be a challenge for anyone, and to synchronise it with the action of a film while building coherent musical structures out of the player’s mind is a tour de force. This was no mere evocation of the Wurlitzer style of the film’s own period, but rather of the powerful and harmonically adventurous qualities of Romantic and post-Romantic music, particularly the great French masters. Louis Vierne’s vocabulary was not far away, and that of others of his time.

Battiwalla conceded the place of Gounod’s score in the film, too, quoting from it in the early scenes and at the point where the "Jewel Song" is visible on-screen, though he didn’t linger with it to test Carl Davis’s point to death – its blander harmonies and simplicity made a great contrast to the gothic and macabre evocations of his playing for the scarier scenes. He’d studied the ballet sequences in the film, too, so his simulated dance music overcame the rhythmic hiccups which the celluloid itself presents to the unwary accompanist.

The RNCM organ, just over 40 years old and built by the Austrian firm of Hradetzky, was designed to include a wide variety of stylistic and national tone qualities, and is a remarkably versatile instrument for its size. There are some wonderfully fiery French-style reed stops and fairly esoteric mutations: Battiwalla got every ounce of spookiness from those, more so than a "straight" organ performance would ever probably accommodate, with trills and tremolandos in profusion. And for those subterranean organ recitals by the composer-organist of the Opéra cellars, he switched to the classic French weirdness of Vox Humana and tremulant – almost another organ sound within the organ’s own palette.

The film is notable for a long sequence of colour images – hand-painted, frame-by-frame originally – for the Bal Masqué scene, and here he found yet more audible colour within the organ’s resources. That, the themes for the torture chamber and near-death experiences of the hero, and the final chase through the streets of Paris – like a French symphonic toccata-final gone over the top – were magnificent examples of musical creativity. It was a real multi-media achievement.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

Add comment