Orhan Pamuk: Istanbul, Memories and the City review – a masterpiece upgraded | reviews, news & interviews

Orhan Pamuk: Istanbul, Memories and the City review – a masterpiece upgraded

Orhan Pamuk: Istanbul, Memories and the City review – a masterpiece upgraded

With its treasury of old photos doubled, this classic memoir still beguiles

Along with Balzac’s Paris and Dickens’s London, Orhan Pamuk’s Istanbul now ranks as one of the most illustrious author-trademarked cities in literary history. Yet, as Turkey’s Nobel laureate told me during a Southbank Centre interview last month, he never set out to appropriate his home town as a sort of personal brand: it was simply the beloved backdrop of his childhood and youth.

You can understand his frustration. So much else happens in Pamuk’s novels beyond the obliteration of decaying Ottoman mansions, misty winding lanes and quaint artisan shops by high-rise towers, urban freeways and shopping malls. Newly translated, The Red-Haired Woman spans within its fast-paced, wide-angled 250-odd pages (almost a short story, by his expansive standards) the generational war between fathers and sons, the hidden affinities linking the religious, conservative and secular, liberal sides of Turkish life, the simultaneous appeal of both “Eastern” and “Western” archetypes to people raised on this great civilisational fault-line, and the uncanny way that “The things you hear in old myths and folk-tales always end up happening in real life”.

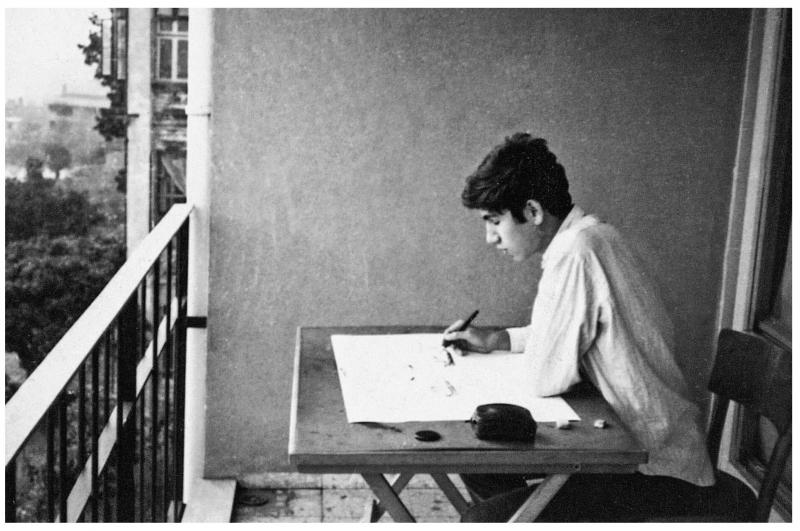

But, inevitably, the transformation of Istanbul’s fabric and ambience still looms large. When the hero Cem, now a property magnate, returns after a quarter-century to the country town where he worked as a well-digger (itself a wonderful metaphor for Pamuk’s art of emotional and cultural archaeology), he finds that the metropolis has spread to swallow it whole. The idyllic plateau where he searched for water with the pious, kindly master-digger Mahmut, and fell under the spell of a flame-haired actress in a Maoist troupe, has become a “concrete labyrinth”. Where goats roamed, supermarkets, kebab stalls, seven-storey apartments, warehouses and workshops sprawl.  Torn, like so many Pamuk protagonists, between old and new ways, Cem regrets the loss of traditional charm and grace even as he makes his fortune from galloping modernisation. That ambivalence serves Pamuk as sort of creative aquifer that never runs dry. It flows too through the new, lavishly illustrated edition of his memoir Istanbul: Memories and the City. Originally published in 2003, and superbly translated by Maureen Freely, the book explored Pamuk’s childhood and adolescence as a moody loner and aspiring painter who switched medium, from images to words.

Torn, like so many Pamuk protagonists, between old and new ways, Cem regrets the loss of traditional charm and grace even as he makes his fortune from galloping modernisation. That ambivalence serves Pamuk as sort of creative aquifer that never runs dry. It flows too through the new, lavishly illustrated edition of his memoir Istanbul: Memories and the City. Originally published in 2003, and superbly translated by Maureen Freely, the book explored Pamuk’s childhood and adolescence as a moody loner and aspiring painter who switched medium, from images to words.

Amid his poignant, nuanced and ruefully comic portrait of the artist as a young man in the shadow of faded glories, both domestic and imperial, Pamuk scattered 206 old monochrome photographs. Each one appeared uncaptioned, but attached by theme or atmosphere to the surrounding text. These selections from the Pamuk family's albums, from tourist postcards, official records, newspaper stories, and the documentary archives of a disappearing city built up by local photographers such as Ara Güler and Achilles Samandji, complemented his wistful but witty reminiscences. This combination of gorgeous words and eerily evocative images generated a magical alchemy. As Pamuk writes in the preface to this new edition, “as much as this book was going to be about the city’s streets, bridges, people, landscapes, ships, traffic and history, it must also concern itself with the feelings that all of these elements elicited”. Taken together, the memoir and the photos would “make visible the emotions embodied by the city of Istanbul in the 20th century”.

Now, expanding just as Pamuk’s city has, those 206 black-and-white photographs have grown to a total of 439. Beautifully produced, this embellished volume – with Pamuk’s new prefatory essay a welcome addition to the text – must rank as the most gloriously bittersweet of all coffee-table books. Ideally, that coffee table should be a scuffed and chipped Ottoman heirloom, bearing the ancient stains that testify to romantic trysts, family quarrels and long-forgotten business deals. However, some streamlined Scandinavian number from the 1960s would do almost as well. Both in his narrative and his chosen photos, Pamuk shows that the smart, “Westernised” modernity pursued by his family and much of the Istanbul bourgeoisie during the post-war decades now looks as touchingly archaic as the battered relics – the mosques, the pharmacies, the palaces, the trams, the ferries, the trains, the tenements, the street-vendors – of the old city so spookily resurrected in this book. In both pictures and text, the decline and fragmentation of his once-grand and once-united family matches the attritional slide towards ruin and redundancy experienced by so many subjects – human and non-human – of the photos he selects. Wooden houses, rusting steamers, corner cafes, waterside mansions: all decay with a sad, regretful smile, as does the happiness of homes and clans, or the prosperity of crafts and trades. In both its visual and its verbal dimensions, Istanbul: Memories and the City reveals that Pamuk grew as a man and artist amid embers and ashes. The aftermath of disastrous fires, in this city once built of wood, fills many piquant pictures. Entranced but repelled by the beauty of decline, the fledgling painter-writer sought simultaneously to escape the distressed city and plunge into its depths of loss. As a teenager, he aspired to be a “radical Westerniser”, and yet “another part of me yearned to belong to the Istanbul I had grown to love, by instinct, by habit, and by memory”. Wandering the shabbily lovely alleys, quays, courtyards and cemeteries so entrancingly evoked in these photogaphs, the young Pamuk found that “the melancholy to which the city bows its head – and at the same time claims with pride – began to seep into my soul”. As the venerable city rotted, the poet of hüzün matured.

In both pictures and text, the decline and fragmentation of his once-grand and once-united family matches the attritional slide towards ruin and redundancy experienced by so many subjects – human and non-human – of the photos he selects. Wooden houses, rusting steamers, corner cafes, waterside mansions: all decay with a sad, regretful smile, as does the happiness of homes and clans, or the prosperity of crafts and trades. In both its visual and its verbal dimensions, Istanbul: Memories and the City reveals that Pamuk grew as a man and artist amid embers and ashes. The aftermath of disastrous fires, in this city once built of wood, fills many piquant pictures. Entranced but repelled by the beauty of decline, the fledgling painter-writer sought simultaneously to escape the distressed city and plunge into its depths of loss. As a teenager, he aspired to be a “radical Westerniser”, and yet “another part of me yearned to belong to the Istanbul I had grown to love, by instinct, by habit, and by memory”. Wandering the shabbily lovely alleys, quays, courtyards and cemeteries so entrancingly evoked in these photogaphs, the young Pamuk found that “the melancholy to which the city bows its head – and at the same time claims with pride – began to seep into my soul”. As the venerable city rotted, the poet of hüzün matured.

Pamuk’s introduction notes that, since the first edition, another wave of technological change has arrived to rob the city of its memories. Photography studios in Istanbul used to house archives of old negatives available to plunder as a visual inventory of lost souls and vanished scenes. Digital photography has consigned those records to oblivion but, in reaction, Istanbul nostalgia has exploded to become a cottage industry, with the photographs Pamuk employs now much in demand. Yesterday’s worthless ephemera become tomorrow’s precious curios: “Of course we care about things only once we’ve lost them.” As visitors will know, a dinky vintage tram runs down the middle of the fabled İstiklal Caddesi. Where others market kitsch, however, Pamuk makes true art.

Pamuk’s introduction notes that, since the first edition, another wave of technological change has arrived to rob the city of its memories. Photography studios in Istanbul used to house archives of old negatives available to plunder as a visual inventory of lost souls and vanished scenes. Digital photography has consigned those records to oblivion but, in reaction, Istanbul nostalgia has exploded to become a cottage industry, with the photographs Pamuk employs now much in demand. Yesterday’s worthless ephemera become tomorrow’s precious curios: “Of course we care about things only once we’ve lost them.” As visitors will know, a dinky vintage tram runs down the middle of the fabled İstiklal Caddesi. Where others market kitsch, however, Pamuk makes true art.

- Istanbul – Memories and the City: the Illustrated Edition by Orhan Pamuk (translated by Maureen Freely), Faber & Faber, £25

- The Red-Haired Woman by Orhan Pamuk (translated by Ekin Oklap), Faber & Faber, £16.99

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Add comment