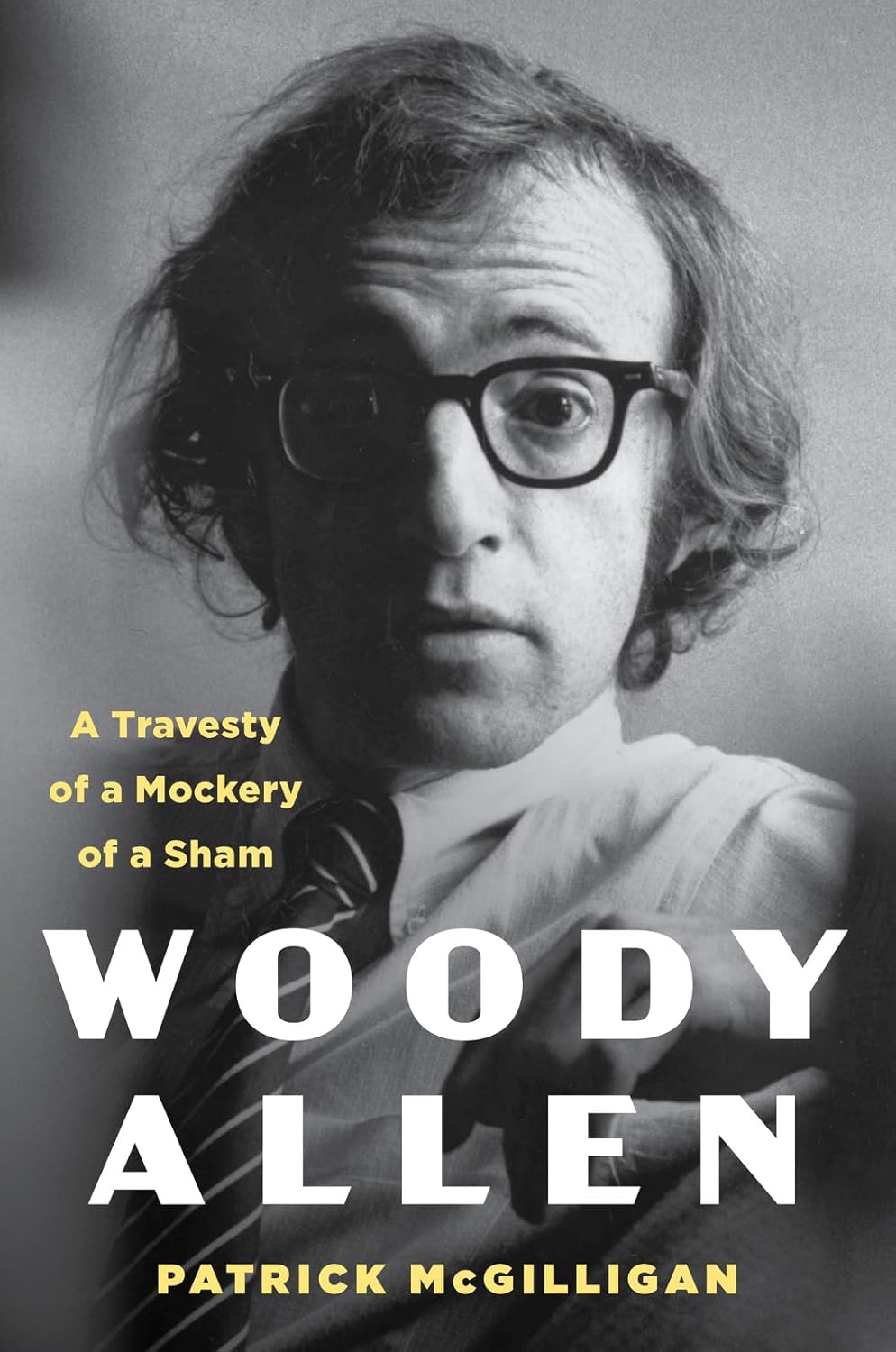

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories | reviews, news & interviews

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan’s biography of Woody Allen weighs in at an eye-popping 800 pages, yet he waits only for the fourth paragraph of his introduction before mentioning the toxic elephant in the room: i.e. the sad fact that, despite never having been charged with – let alone convicted of – any crime, Allen in 2025 is, to all intents and purposes, cancelled.

So let’s deal with that first. The reason for Allen having suffered what McGilligan calls “the living death of being declared an unperson” has transmogrified over the years. Initially, he was weighed in the balance of public opinion and found wanting, for his scandalous affair with the adopted daughter of his partner and sometime muse, Mia Farrow, in 1992. As the years and decades have passed, however, and Allen and Soon-Yi have enjoyed a stable marriage that’s produced two happy, grown-up kids, the focus has shifted to the allegation made against Allen by Farrow in the midst of that messily public breakup: that Allen had sexually molested their daughter, Dylan.

McGilligan expresses no opinion as to Allen’s guilt or innocence. He simply lays out all the facts, soberly and meticulously, and leaves us to make our own assessment. Allen endured two lengthy investigations (one in the State of Connecticut, one in New York), and was cleared by both. He passed a lie detector test. Meanwhile, despite having accused Allen of molesting their daughter, Farrow still lobbied for the role that eventually went to Diane Keaton in "Manhattan Murder Mystery", and sued for her $350,000 fee, according to the terms of her "play or pay" contract.

The Yale-New Haven Hospital child-abuse specialists who investigated Farrow’s claim and “repeatedly interviewed Allen, Farrow, and Dylan”, concluded: “It is our expert opinion that Dylan was not sexually abused by Mr. Allen.” They also noted “a rehearsed quality” to Dylan’s account of events, and testified that “It’s quite possible – as a matter of fact, we think it is medically probable – that she stuck to that story over time because of the intense relationship she had with her mother.” In other words, the strong likelihood is that Farrow made the story up and brainwashed her own child out of spite. Yet Allen is the one regarded as a monster and subjected to what McGilligan calls “the anti-Allen hysteria, which echoes the show business witch hunt during the McCarthy era”. Go, as Americans say, figure.

Anyway, if you’re part of the cadre that’s convinced of Allen’s guilt despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary, you’re unlikely to be interested in an 800-page biography, and are in all probability no longer reading this review. So how is the book? Well, it’s a brisk, entertaining read, offering a full, highly detailed, even-handed account of a story many readers will already know quite well. No big revelations emerge, but there’s a lot of fascinating colour, particularly on the early years and Allen’s meteoric rise from quirky kid growing up in a Jewish neighbourhood of mid-20th century Brooklyn, via precocious teenage gag-writing for established New York columnists and famous comics such as Sid Caesar, all the way to becoming one of the world’s most famous, successful, unique, and (pre-cancellation) beloved film-makers.

What comes across repeatedly is that whatever Woody Allen’s personal traits – some of them eccentric bordering on sociopathic – as an artist he has always been workaholic going-on monomaniacal. Whatever else he may be doing, whether directing, in post-production, defending himself against lawsuits, or even on holiday, he never stops juggling projects and writing, writing, writing, as though – like the shark in Annie Hall – if he stops, he’ll drop dead.

McGilligan covers every film (not to mention play, screenplay, standup routine, acting role, New Yorker short story, clarinet performance, etc.), from the dizzying heights of Allen’s 70s and 80s heyday, through all the ups and downs of the decades that followed. There’s plenty of interesting background on the making of acknowledged Allen classics such as Annie Hall and Hannah and Her Sisters, but not much analysis of the films. He’s scrupulously fair, though, often finding things to like about some of Woody’s less critically favoured and/or commercially underwhelming films.

McGilligan covers every film (not to mention play, screenplay, standup routine, acting role, New Yorker short story, clarinet performance, etc.), from the dizzying heights of Allen’s 70s and 80s heyday, through all the ups and downs of the decades that followed. There’s plenty of interesting background on the making of acknowledged Allen classics such as Annie Hall and Hannah and Her Sisters, but not much analysis of the films. He’s scrupulously fair, though, often finding things to like about some of Woody’s less critically favoured and/or commercially underwhelming films.

In fact, you could say that he’s fair to a fault, because he doesn’t address the unavoidable fact that the quality of Allen’s films declined markedly in the 1990s then nosedived in the Noughties. The last Woody Allen film that even a committed fan could reasonably call "great" was Crimes and Misdemeanors, in 1989. The best of his 90s films were merely quite good, while the post-Millenium output has been mired in self-pastiche, consisting overwhelmingly of cheesy, heavy-handed, chronically unsubtle duds.

Could it be the old cliché of the settled artist, happy in love, losing his edge? Or was the artistic decline somehow related to the lack of judgement that led Allen to express surprise that taking up with his girlfriend’s adopted daughter, less than half his age, would prove controversial? McGilligan doesn’t answer this question because he doesn’t really acknowledge the decline.

Polling film critics and writers on their favourite Allen films, McGilligan found that “more than one admitted a wariness of expressing any sort of approval of Woody Allen”. One woman went so far as to say “she did not hold a single Woody Allen movie in favorable regard”, explaining she wasn’t “interested in how well Hitler painted”. I bet she’s fun at parties. A total of 104 writers did take part and, quite surprisingly, their Top 10 most popular films include four post-80s works: Match Point, Midnight in Paris, Vicky Cristina Barcelona, and Blue Jasmine.

Like many critics, McGilligan reckons Match Point a return to form, calling it a “perfect Hitchcockian thriller”, worthy of “comparisons to the George Stevens film A Place in the Sun”; watching it once again for this review, I found those lofty allusions do the film no favours. It’s middling, at best, and if you took away Scarlett Johansson’s precocious charisma, it’d collapse like an over-cooked souffle. Penelope Cruz is wonderful in Vicky Cristina Barcelona, but the film isn’t worthy of her, and is marred by one of the most egregiously irritating voiceover narrations ever recorded. Midnight in Paris has its charms, and works as a sort of meta-Allen film, being a warm-toned mélange of many of his perennial themes and obsessions: Freud, Hemingway, Paris, jazz, existentialism, the romantic allure of the pure artistic life. Blue Jasmine is good enough to stand out starkly as the exception to the post-90s rule, buoyed by a career-best performance from the great Cate Blanchett.

McGilligan is on shakier ground when trying to talk up turkeys such as Cassandra’s Dream (“almost as gripping as Match Point”), or To Rome With Love (“much of it is entertaining”). The “few exquisite scenes” in the excruciating Magic in the Moonlight eluded me, as did the “wonderful scenes” in the farrago that was Whatever Works. But it’s a credit to McGilligan’s fair-mindedness that he tries to find the best in even the worst films. In any case, if you like Woody Allen movies then a particular film needn’t be a classic in order for you to get something out of it. McGilligan’s claim that “In any other context Café Society would have been greeted as an elegantly crafted if antediluvian jewel from an old master” may be a little over-stated, but the film does have appealing aspects and, taken on its own terms, is quietly enjoyable.

People rushing to judge Allen on his private life, even leaving aside hysteria and knee-jerk sanctimony, are making a category error. Allen and Farrow are not run-of-the mill people. Even by celebrity standards, they were always a pair of odd ducks. Their eccentricities could fill a book. Farrow adopted kids with the casual frequency most women would apply to changing hairstyles. At one point, she presided over a brood of four biological and 10 adopted children, most of whom, McGilligan notes, were – individually and/or in groups – undergoing psychoanalysis, all financed by Woody Allen, to the tune of $1,750 a week. Even her dog had its own $150 per hour analyst; but then it was a Bichon Frise, a breed well-known for their neuroses.

Whatever you think of Allen as a person, there is no denying that his films, and his humour, have brightened the lives of millions of people for several decades. More than this, Allen in his prime became symbolic of New York, and by extension of America. Even now, with the US having fallen to fascism, his films speak to some of the positive aspects that once made that country a beacon for so many people all around the world.

In a famous scene in Manhattan, Allen’s character Isaac lies on a sofa, monologising into a tape recorder about the vicissitudes of life, and enumerating the things that make it worthwhile: “Groucho Marx, to name one thing... Wilie Mays... the 2nd movement of the Jupiter Symphony... Louis Armstrong, recording of Potato Head Blues... um... Swedish movies, naturally... Sentimental Education by Flaubert... uh... Marlon Brando, Frank Sinatra…” For many of us, Woody Allen movies would have been on that list. There is no reason to strike him off just because he’s a collateral victim of cancel culture. McGilligan’s biography is comprehensive, diligent, and fair. It may well become definitive. It deserves to be read with an open mind.

- Woody Allen: A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham (Harper Collins, £40)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

This rock solid testimony

This rock solid testimony from his other son should've completely silenced everyone else: http://mosesfarrow.blogspot.com/2018/05/a-son-speaks-out-by-moses-farrow...

Great write-up

Great write-up