Sunday Book: Haruki Murakami - Absolutely on Music | reviews, news & interviews

Sunday Book: Haruki Murakami - Absolutely on Music

Sunday Book: Haruki Murakami - Absolutely on Music

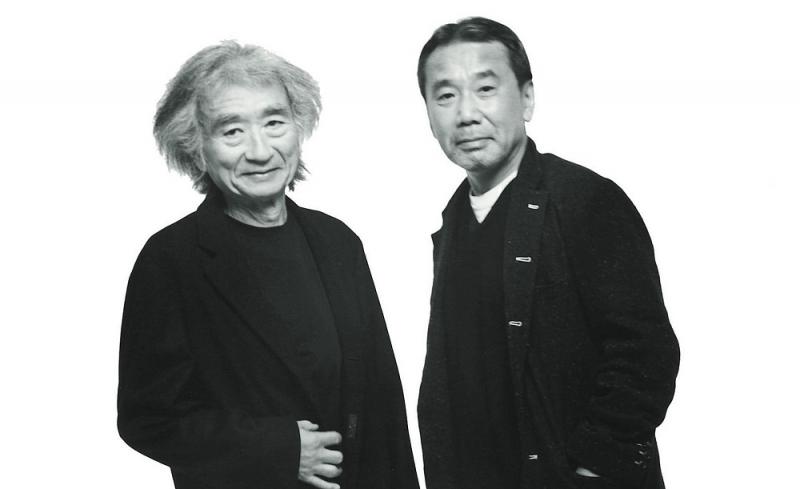

In 'Conversations with Seiji Ozawa', cult novelist and star conductor make sweet sounds

Every fan of his fiction knows that Haruki Murakami loves jazz and lets the music play throughout his books. Yet in this 320-page dialogue between the novelist and his equally eminent compatriot, conductor Seiji Ozawa, it’s the veteran maestro of the baton who makes the boldest lateral leap between their shared Japanese culture and the Western forms they admire.

Speaking of his beloved Louis Armstrong, Ozawa - unlike the snobbish jazz police - has kind words for the ageing entertainer as well as for the pre-war virtuoso. “You know how we talk about artistic ‘shibumi’ in Japan, when a mature artist attains a level of austere simplicity and mastery?” Ozawa asks Murakami. “Satchmo was like that.”

Now 81, the former chief conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (for a record 29 years) and the Vienna State Opera has settled into a reflective autumn as teacher, mentor and guru. An operation for oesophageal cancer in 2010 created the space and time for long-distance recuperation that allowed this book to happen. In Tokyo first, then at his Swiss summer school near Geneva, Ozawa sat down with Murakami to talk music with an unpretentious grace that itself embodies “shibumi”. Enraptured, occasionally nerdish, discussions of favourite recordings of Beethoven, Brahms, Stravinsky and Mahler ripple out into wider musings on craft and performance, art and ageing. As Murakami writes, these conversations stitched a “rare silver lining” into the cloud of illness - although the sun breaks through as Ozawa picks up the baton again.

By itself, such a trove of insight drawn from a stellar career would count as a notable event. Murakami’s presence on the other side of the mike changes the game, however. As a top-level literary-musical summit, the book has precious few counterparts - one being Daniel Barenboim’s set of conversations with Edward W. Said, Parallels and Paradoxes. Not only do twin doors open into the orchestral maestro’s workshop and the superstar novelist’s studio. Murakami works hard to knock what he calls “an effective passageway” though the “high and thick” wall that separates the music-loving literary amateur from the seasoned professional.

True, the result can ramble, dawdle and even lose its way in the manner of Murakami’s digressive story-telling style - or, maybe, of the notoriously snail’s-paced version of the Brahms first piano concerto that Glenn Gould recorded with Leonard Bernstein (one of the pieces scrutinised here). At best, though, these servants of sister muses maintain an easy rapport. It sheds fresh light both on the “lone craftsman” author, and the conductor whose devotion to a “communal work of art” may hide a “deep fog of solitude”.

True, the result can ramble, dawdle and even lose its way in the manner of Murakami’s digressive story-telling style - or, maybe, of the notoriously snail’s-paced version of the Brahms first piano concerto that Glenn Gould recorded with Leonard Bernstein (one of the pieces scrutinised here). At best, though, these servants of sister muses maintain an easy rapport. It sheds fresh light both on the “lone craftsman” author, and the conductor whose devotion to a “communal work of art” may hide a “deep fog of solitude”.

Running and music have always kept pace among Murakami’s obsessions. The novelist - who once owned a jazz bar in Tokyo called Peter Cat - soaks his prose with sounds. For example, the recent novel Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage nods in its title to Liszt’s piano odyssey Années de pèlerinage. It has characters who chew over that work’s finest recording (Lazar Berman or Alfred Brendel?), and sends the questing hero into a sort of enchanted forest where he meets a mysterious jazz pianist who plays Thelonious Monk’s “Round Midnight”. When, in his futuristic and dystopian epic 1Q84, Murakami made Janáček’s Sinfonietta a sort of theme-tune or leitmotif, worldwide sales of that work spiked for a while.

Most aficionados tend to focus on the jazz and pop allusions strewn across his stories as signals, atmospheres and character indicators by the author of Norwegian Wood. But the Western classical repertoire that occupies him in this book has served just as well as both “stimulus” and “source of peace”. For Murakami, “jazz and classical music are fundamentally the same.”

As Absolutely on Music shows, the writer cherishes the sort of performances that express the creative freedom he values most in a Charlie Parker or Miles Davis. When Ozawa and Murakami listen to Gould and Bernstein’s recording of Beethoven’s concerto, the latter marvels that the maverick Canadian pianist “changes the rhythm so freely - if he were a writer, I might say it’s the way he delivers his sentences.”

You have the impression of Murakami hunting down in musical performances an equivalent of the fluid, free-form, almost improvisational quality that makes his own prose so captivating - or, to sceptical critics, so loose and muddled. As the pair delve into the third movement of Mahler’s first symphony, Murakami paints a disguised self-portrait. When he scorns Herbert von Karajan’s “visceral intolerance for the hybridity, the vulgarity, the disunity of Mahler” and insists that a tavern ditty, a funeral march and a klezmer melody may jostle in his symphonies on equal terms and with no “sense of inevitability” about the music’s final destination, you glimpse Murakami gazing into a kind of sonic mirror.

Luckily, in Ozawa he has a like-minded interlocutor. A Murakami dialogue with Karajan - who figures here as the archetypal Germanic stickler, orthodox and dour - might have lasted all of 30 seconds. Sometimes, this cosy kinship of baton-wielder and keyboard-pounder feels a trifle gooey. When they play Mitsuko Uchida’s version of the same Beethoven concerto, Murakami supplies the stage-directions: “This is truly miraculous music-making. The two listeners groan simultaneously.” Too much of that and the reader will groan. Like any sensitive conductor, though, the interviewer knows when to vary pace and weight.

This relaxed, companionable tone - carried into English with an agreeably light touch by translator Jay Rubin - masks a few disparities. The serene elder statesman, Ozawa looks back in wonder, appreciation and occasional regret. He even worries that his creamy and polished Boston band had a tendency “to make sounds that are too nice”. In contrast, Murakami the creative magpie is not only paying homage to a hero but scavenging the recorded repertoire for music he can put to work. Sometimes you sense the writer’s eye, or ear, on the next - or the last - book.

The novelist flatly states that “you can’t write well if you don’t have an ear for music”, and that all good prose “has to have an inner rhythmic feel that propels the reader forward.” Despite the odd longueur, these dialogues have that. They add up to a sprawling feast of Mahler-style “polytonality” - or, alternatively, the sort of protean jam-session that Monk and Parker relished.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment