Reissue CDs Weekly: Peter Zinovieff | reviews, news & interviews

Reissue CDs Weekly: Peter Zinovieff

Reissue CDs Weekly: Peter Zinovieff

Essential collection of the influential and pioneering electronic musician

Peter Zinovieff: Electronic Calendar – The EMS Tapes

Peter Zinovieff: Electronic Calendar – The EMS Tapes

Roxy Music’s June 1972 debut appearance on The Old Grey Whistle Test found them miming to “Ladytron” from their debut album, released that week. A prime focus for the camera was Eno, in a fake leopard-skin jacket and shiny gold gloves. Twiddling knobs and waggling a joystick, he stood at what was obviously an instrument but not a conventional one. There was no keyboard and the noises generated bubbled and swooped. This was an EMS synthesiser.

The EMS synthesiser was British and a favourite of Hawkwind, Pink Floyd, Paul McCartney, The Who and David Bowie, whose own example was displayed at the David Bowie Is exhibition. The Aphex Twin is a fan of EMS. Although models came with the keyboard Eno had no time for, the synthesiser wasn’t great at staying in tune so most aficionados used it to create interesting noises as colour for their music. Nonetheless, EMS marketed their affordable instruments as right for any household. They even proclaimed that every picnic needed their Synthi model. In the ad (pictured below left), the knobs Eno had handled rested in verdant grass.

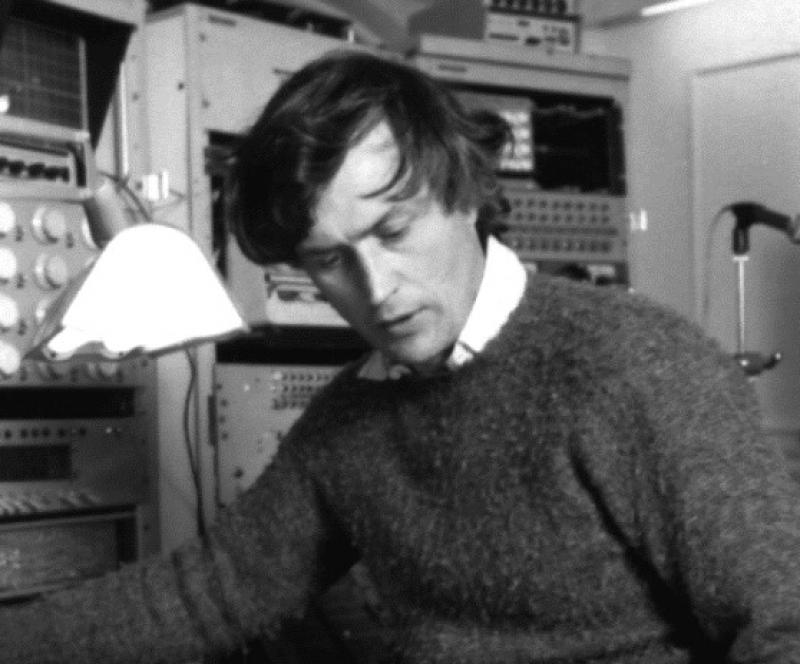

Peter Zinovieff was behind this important and pioneering British company. Electronic Calendar – The EMS Tapes is the first ever overview dedicated to his own music. Disc One collects two sets of collaborations, the first with British composer Harrison Birtwistle, the second with the radical German composer Hans Werner Henze. Disc Two collects 14 tracks, two of which are individual collaborations with the computer artist Alan Sutcliffe and the British composer Justin Connolly: the remaining 12 are credited to Zinovieff alone

Until now, the narrative surrounding Zinovieff has been lacking a soundtrack from his own music. While it was possible to hear an EMS synthesiser on Pink Floyd’s “On the Run”, The Who’s “Won’t Get Fooled Again” or even Portishead’s “We Carry on”, finding recordings of it in the hands of its inventor was extremely difficult. Electronic Calendar plugs a major gap in the understanding of British music.

Until now, the narrative surrounding Zinovieff has been lacking a soundtrack from his own music. While it was possible to hear an EMS synthesiser on Pink Floyd’s “On the Run”, The Who’s “Won’t Get Fooled Again” or even Portishead’s “We Carry on”, finding recordings of it in the hands of its inventor was extremely difficult. Electronic Calendar plugs a major gap in the understanding of British music.

Zinovieff (born in Britain in 1933) had Russian parents and was employed as a mathematician by the Air Ministry during World War II. He then worked in atomic physics but had other interests. British tape music pioneer Daphne Oram had shown him how to create music with splicing. Dissatisfaction with this as a process led him to formulate the idea of an electronically controlled recording studio. In 1964, with funds from the sale of his wife’s wedding tiara, he bought a computer and installed it in the garden shed of his Putney home. From ex-army equipment, he and engineer David Cockerall assembled amplifiers, filters, noise generators, ring modulators and 384 oscillators.

In 1966, Zinovieff joined Unit Delta Plus, the ensemble formed by ex-BBC Radiophonic Workshop mainstays Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson. The idea was to make music and effects for commercials, soundtracks and themes. Zinovieff found he did not share that vision, and soon split from them. He wanted to experiment for the sake of it, rather than working to a client’s brief. With Tristram Cary and David Cockerell, he formed Electronic Music Studios (EMS) in 1969 and was soon marketing the synthesisers they manufactured. Fractionally larger than a briefcase, they were more manageable than the wall-sized American Moog units. They were relatively cheap too. The EMS VCS3 sold for £330 in 1969. Its keyboard was an additional £150. He also set up the Musys studio in the basement of his house at 49 Deodar Road, Putney (pictured below right).

Robert Moog was amongst the visitors to Zinovieff’s house-cum-studio-cum-workshop, and played Walter Carlos’s Switch-on Bach album to Zinovieff, Cockerell and a horrified Birtwistle, who stormed out of the room appalled at the havoc wreaked on Bach. Others who dropped in included Bowie, McCartney, Pink Floyd, and Tangerine Dream. Zinovieff was at home – literally – with the worlds of the avant-garde, experimental, pop and rock. EMS went bankrupt in 1979

Robert Moog was amongst the visitors to Zinovieff’s house-cum-studio-cum-workshop, and played Walter Carlos’s Switch-on Bach album to Zinovieff, Cockerell and a horrified Birtwistle, who stormed out of the room appalled at the havoc wreaked on Bach. Others who dropped in included Bowie, McCartney, Pink Floyd, and Tangerine Dream. Zinovieff was at home – literally – with the worlds of the avant-garde, experimental, pop and rock. EMS went bankrupt in 1979

Electronic Calendar opens with the Zinovieff-Birtwistle collaboration “Chronometer ’71”. Rather than being played on an EMS synthesiser, it is an extraordinary piece created by Zinovieff from recordings of Big Ben striking and the clock mechanism at Wells Cathedral. Birtwistle wrote a graphic score and, once the recordings were made on tape, they were fed through the computer and then committed to another tape. In one move, Zinovieff was both sampling and sequencing before both became commonplace in the digital world to come. From an aural perspective, “Chronometer ’71” is absorbing, jarring and utterly enthralling.

Of the Zinovieff-Hans Werner Henze works, created in the same way with Zinovieff realising the composer’s vision, “Tristan”, first released in 1973, takes this approach even further by melding computer-processed sounds with orchestra and human voice to uncanny effect.

Disc Two has further examples of computer-tape music but also what appear to be (see the note below about frustrations with the annotation of his release) recordings made with EMS synthesisers. The short and brilliant “Un Known 1” could actually be The Aphex Twin, while the bubbling, pulsing “Tarantella” prefigures acid house. Best of all is the fantastic, jagged “January Tensions”, which seems to mix computer-processed music with synthesiser-generated sounds. Ironically, “Lollipop for Papa” begins like a trite Walter/Wendy Carlos confection but soon turns into a crazy sonic kaleidoscope sounding like a cut-up of Switched-on Bach. It may be a piss take of Carlos. (Pictured left: the EMS AKS briefcase-sized synthesiser, the model owned by David Bowie)

Disc Two has further examples of computer-tape music but also what appear to be (see the note below about frustrations with the annotation of his release) recordings made with EMS synthesisers. The short and brilliant “Un Known 1” could actually be The Aphex Twin, while the bubbling, pulsing “Tarantella” prefigures acid house. Best of all is the fantastic, jagged “January Tensions”, which seems to mix computer-processed music with synthesiser-generated sounds. Ironically, “Lollipop for Papa” begins like a trite Walter/Wendy Carlos confection but soon turns into a crazy sonic kaleidoscope sounding like a cut-up of Switched-on Bach. It may be a piss take of Carlos. (Pictured left: the EMS AKS briefcase-sized synthesiser, the model owned by David Bowie)

Electronic Calendar’s two CDs are held inside the front and back covers of a casebound, 62-page book. The design and layout are clear and precise. Despite the splendid package, there are two major problems.

The first centres on the failure to annotate the track list with information on dates and sources. Only the title of each composition is listed. In the main, the when, where and why of anything heard is a mystery. There is no track-by-track commentary. Obviously, from its title, the Zinovieff-Birtwistle collaboration “Chronometer ’71” dates from 1971. The press release says that, “in 1967 [the track] 'ZASP' won second prize at an IFIP (International Federation for Information Processing) congress, a society dedicated to computer arts.” So that dates this track. Similarly, the press release also notes that, “Now is the Time to say Goodbye” is “the last piece of music recorded in the EMS studio before it was destroyed by a flood in London’s National Theatre in 1979” – so that dates it to 1979 or earlier. Neither of these two dates is noted in the package. This oversight is extremely frustrating, as it is essential to know what is being heard. (Pictured right: an example of Zinovieff's computer music scores)

The first centres on the failure to annotate the track list with information on dates and sources. Only the title of each composition is listed. In the main, the when, where and why of anything heard is a mystery. There is no track-by-track commentary. Obviously, from its title, the Zinovieff-Birtwistle collaboration “Chronometer ’71” dates from 1971. The press release says that, “in 1967 [the track] 'ZASP' won second prize at an IFIP (International Federation for Information Processing) congress, a society dedicated to computer arts.” So that dates this track. Similarly, the press release also notes that, “Now is the Time to say Goodbye” is “the last piece of music recorded in the EMS studio before it was destroyed by a flood in London’s National Theatre in 1979” – so that dates it to 1979 or earlier. Neither of these two dates is noted in the package. This oversight is extremely frustrating, as it is essential to know what is being heard. (Pictured right: an example of Zinovieff's computer music scores)

The second problem centres on the book, which collects separate essays. These seem to be either written specially for this release or extracts from Zinovieff’s diaries, or text drawn from EMS catalogues and concert programmes. There are no proper credits, though three sections are credited to Zinovieff (one is dated to "Spring 1968"). As this unwieldy text is not a chronological account, there is no clear sense of the story behind what is heard. The lack of clarity and opaqueness are, again, extremely frustrating

Electronic Calendar isn't a user-friendly release. Nonetheless, it's an essential one.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Add comment