Storyville: Masterspy of Moscow - George Blake, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Storyville: Masterspy of Moscow - George Blake, BBC Four

Storyville: Masterspy of Moscow - George Blake, BBC Four

Intriguing espionage life-story of the British double-agent, and a brief encounter today

“The righteous traitor” must be as provocative a subtitle as any when the subject is espionage. Director George Carey nevertheless used it in this highly revealing film about George Blake, the “spy who got away”, which proved as much about the anatomy of treachery – its correlation with the uneasy relationship of the outsider to a dominant establishment – as it was an investigation of the intelligence world in which Blake played so notable a role.

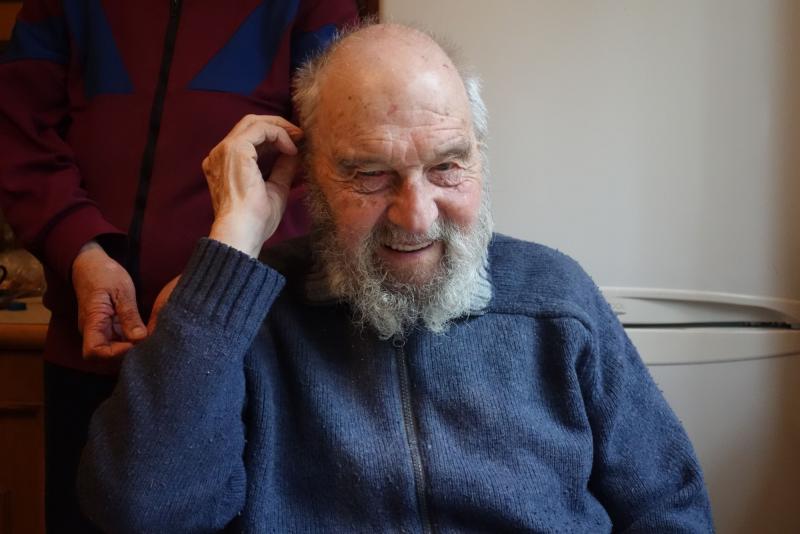

The final rankings of ignominy – who really was the Soviets’ “masterspy”? – may never be decided when it comes to rating which of the British defectors did most damage to their homeland (and, by extension, the non-Communist world of the time), though the Cambridge spies of the earlier generation – Kim Philby (the subject of Carey’s previous film), Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean – probably remain more notorious in the popular imagination. Blake’s story certainly differed from theirs: his ideological conversion to Communism dated from when he was a North Korean prisoner-of-war, rather than Cambridge in the 1930s. And the earlier trio escaped before they were caught, while Blake confessed his involvement with the Soviets under interrogation, and only made it to Moscow after he was sensationally sprung from Wormwood Scrubs prison in 1966 and spirited away via East Germany. He probably lived more happily in his Soviet exile than the rest, too, and we caught a late glimpse, tantalisingly brief, of Blake today, aged 92 and almost blind, living out his days peacefully in the countryside outside Moscow.

If he seemed to yearn in his Russian exile for a homeland, it was for Holland, the country of his birth

Most of all, though, Masterspy of Moscow emphasized how Blake never really was “one of us”, never a member of the British elite who could move effortlessly into intelligence: if he seemed to yearn in his Russian exile for a homeland, it was for Holland, the country of his birth, rather than England. His Rotterdam childhood in the Behar family – he would change his name later – certainly wasn’t easy, though after the early death of his distant father the young George was sent to stay in the very different, wealthy world of his paternal Jewish relations in Cairo. It was there that he was exposed to the opinions of a cousin who later became a prominent Egyptian Communist.

As in his Philby film, director Carey was an unobtrusive narrator, allowing his subjects to speak for themselves. He proved lucky that so many were still alive and able to talk so insightfully about their memories: what engaging company these interviewees were, with a French cousin, Sylvie Brabant, filling in much of that family context. (Blake’s first wife Gillian and his children from that marriage were notably absent from the film).

Then there were the professional contacts of Blake’s wartime espionage days, the upper-class SIS secretaries like Iris Peake and Susan Asquith, whose accents alone illustrated the gulf between where they and he came from; another veteran interviewee was Ed Sheffield, an American fellow prisoner-of-war in North Korea, seeing his own days out in rather sunnier climes in Florida. (The British legation in Seoul, where Blake was captured in 1950, pictured below.).Other ex-MI6 colleagues completed the film’s broad cast, alongside espionage historians Alan Judd (MI6) and Tim Weiner (CIA), and Blake’s biographer Roger Hermiston.

But two extended encounters seemed especially revealing: even if the individuals concerned weren’t exactly at the heart of Blake’s story, they somehow conveyed a greater sense of historical atmosphere than other more “official” contacts. We met Michael Randle, the last of the three accomplices who helped Blake escape from prison still alive, as he remembered how, with his wife and children, they smuggled Blake out of the country hidden under the back seat of a Volkswagen camper van. (More could have been said of the later repercussions of that story, when the three were tried, and then acquitted, for that at the beginning of the 1990s, with Blake vowing to return if they had been convicted – but at 90 minutes Masterspy… was already packed).

But two extended encounters seemed especially revealing: even if the individuals concerned weren’t exactly at the heart of Blake’s story, they somehow conveyed a greater sense of historical atmosphere than other more “official” contacts. We met Michael Randle, the last of the three accomplices who helped Blake escape from prison still alive, as he remembered how, with his wife and children, they smuggled Blake out of the country hidden under the back seat of a Volkswagen camper van. (More could have been said of the later repercussions of that story, when the three were tried, and then acquitted, for that at the beginning of the 1990s, with Blake vowing to return if they had been convicted – but at 90 minutes Masterspy… was already packed).

Even more revealing somehow were Louis and Trudy Wesserling, who got to know Blake and his family when they were at the Foreign Office Arabic school in Lebanon at the beginning of the 1960s; Louis was an oilman rather than a diplomat, but they were Dutch, and so the two couples got on especially well. Trudy’s memories of her final meeting with Blake, at a party to celebrate the end of their course, spoke volumes: they were drinking and dancing, and when the subject came to politics, Blake eventually blurted out the question, “Are you one of us?” Politically “red as a brick” herself, as she remembered today, she guessed at something, that he was longing to tell the whole story. Only days later, he would do just that, to both his own amazement (as he recalled in Tom Bower's 1990 television interview that was the film’s most important archive source) and that of his interrogators. He could have kept quiet and walked away, but instead a “dam burst”.

Carey’s closing encounter with Blake proved less revelatory. “Instead of that easy smile, the closed look of a man who can keep secrets came down,” Carey noted when the subject turned to Vladimir Putin, on whose goodwill Blake to some extent depends. How much their belief in Marxism-Leninism survived the experience of Soviet exile remains a crucial retrospective question for all the British spies, and Blake’s likely did (and does) more than that of the others. The contrast of their earlier idealism with the cynicism that’s at the heart of Russian statecraft today coud hardly be starker.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Add comment