The Green Prince | reviews, news & interviews

The Green Prince

The Green Prince

The Israeli-Palestinian struggle explored through a single complex relationship

Finding a clear narrative among the deadly uncertainties of the long-lasting stand-off between Israel and Palestine is a challenge. Israeli documentarist Nadav Schirman, drawing on a real-life story, has honed The Green Prince down into a bare story of the ongoing contact between Gonen Ben Yitzhak, an officer of Israel's Shin Bet intelligence service, and Mosab Hassan Yousef, a young man from the very centre of the Palestinian leadership who becomes his agent.

It’s a remarkably unadorned film, concentrating on the direct testimonies of the two players. They tell their stories direct to camera, the only variety being whether they are framed in half-body shots or as close-ups on faces. Accompanying visual material is largely generic, made up of television newsreel footage of the events which feature in their narratives, or standard (and repeating) surveillance images, from drone, helicopter or vehicle; an electronic musical score (Max Richter, with sound design by Alex Claude) maintains a degree of tension throughout. But it’s mainly the clarity of their words, the implicit story of how the handler manipulates his agent, and the changing balances within their professional relationship, that makes the result so compelling, with the tension of a thriller.

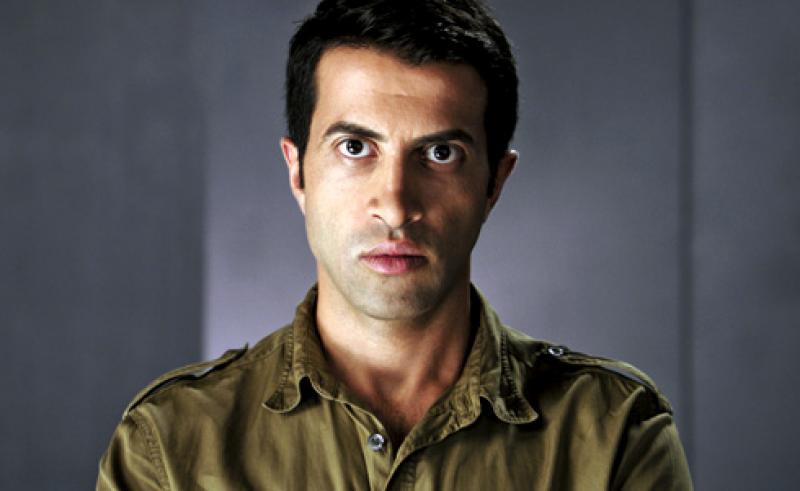

Mosab (main picture) was the 17-year-old son of a prominent cleric and member of the Palestinian resistance movement, a founder of its armed unit Hamas. With his father spending many years in Israeli prisons, his eldest son was left in effective charge of the extended family. Feeling a “right to make the other side feel pain”, Mosab arranged to obtain, though never used, weapons, which led to his arrest.

Mosab (main picture) was the 17-year-old son of a prominent cleric and member of the Palestinian resistance movement, a founder of its armed unit Hamas. With his father spending many years in Israeli prisons, his eldest son was left in effective charge of the extended family. Feeling a “right to make the other side feel pain”, Mosab arranged to obtain, though never used, weapons, which led to his arrest.

His fear on being in prison for the first time – “welcome to the slaughter house,” was the greeting from one of his guards – is palpable, as he’s pushed to breakdown through the standard tactics such as sleep deprivation. It’s at that point he encounters Gonen (pictured, above right), his interrogator. The latter’s task is to bring in his new charge as an agent, using all the resources he has at his command, not least, it turns out, his psychology degree: “recruiting is the art of understanding the person in front of you,” he remembers.

The moment of betrayal doesn’t come immediately – first Mosab spends time in prison, where he sees the murderous way in which Hamas deals with those they suspect of working for the enemy, a first step in his loss of any idealism for those carrying on his people’s struggle through violence. Quite what finally persuades the young man to take this course – he has earlier said that to collaborate with Israel would be worse than raping your mother – may remain elusive, but the sheer accomplishment with which he’s manipulated certainly played a part, combined with Mosab's sense that he can actually save lives. Not only do we know that this actually happened, but Mosab’s sincerity as he recounts it makes us believe him. (A painful incident in Mosab’s personal life may have resulted in his feeling a degree of alienation from his society, too.)

And so he started to work for the enemy, with the Shin Bet codename “The Green Prince”. Gonen certainly knows the value of his prize, comparing Mosab’s privileged position with listening access to the Palestinian hierarchies to the latter have the son of the Israeli prime minister as their agent.

Even if you’ve read the book and already know the story, the power of the film’s conclusion is remarkable

The Israeli knows how to manage his charge, and the “game”, as it’s referred to in one of the chapter titles that structure Schirman’s film, of manipulation begins. It’s a tangled web, with Shin Bet balancing how it reacts to information received from Mosab with the need to protect the source. At the same time Mosab wouldn’t necessarily always follow all instructions, justifying his independence with an articulated sense of his integrity – a word we might take with a pinch of salt coming from a traitor, one who has betrayed not only his people but more crucially his own father, was it not for the evident sincerity with which he speaks. So accomplished was Mosab’s ability to dissemble that the collaboration went on for more than ten years: the only element left a little unexplained here is how he was physically able to avoid suspicion, on the level of concealing the many meetings and even more telephone calls that must have been part of his double life.

The Palestinian also demanded a sense that he was trusted by his minders, one which Gonen gradually extended even when doing so risked breaking the protocols of his service. The results of this increasing empathy with his agent – it’s a situation in which something like Stockholm syndrome works in both directions – would lead to Gonen’s dismissal, and with that the eventual dissolution of Mosab’s collaboration.

The Green Prince is based on the book Son of Hamas that Mosab went on to write after he’d moved to America. Even if you’ve read it and already know the story, the power of the film’s conclusion is remarkable. These two individuals, each of whom has broken ranks with the strict structures of his own society, in turn achieved a mutual understanding of a kind that increasingly evades those respective societies on the widest level.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for The Green Prince

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Add comment