Ballyturk, National Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Ballyturk, National Theatre

Ballyturk, National Theatre

Enda Walsh's unsettling comedy triumphs at the Lyttelton

In his masterly essay in the programme for Enda Walsh's latest play, Colm Tóibín warns against attempting to pin his work to a particular philosophical position, but simply to read into it a metaphor for humanity's efforts to cope with life while knowing that there is no escape from death. And certainly an attempt at blow-by-blow analysis – even understanding – would be a waste of time. Ballyturk is a thing in and of itself.

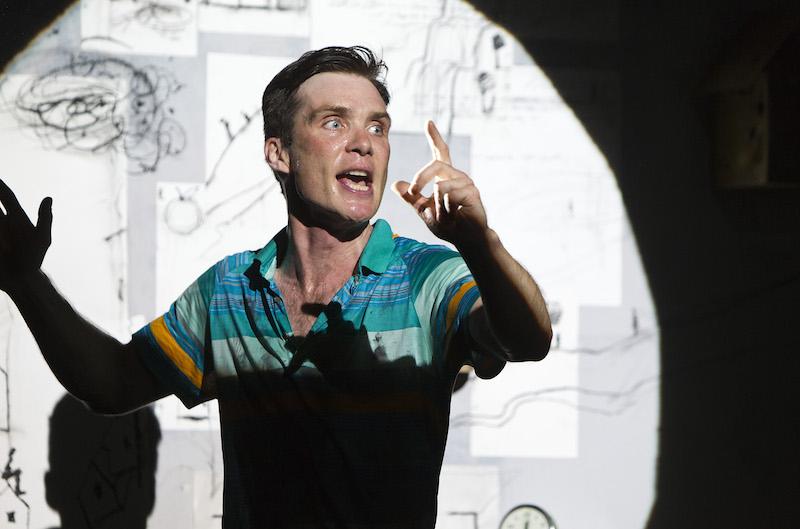

This is what we see. Two friends share a shabby room which they never leave. The setting, we are told, is "No time. No place", but it is also, of course, specifically Irish. Tóibín's description of Walsh's characters as being left "in a Trojan horse with the battles for Troy all over" is apt, although this place has the trappings of a particular, run-down twentieth-century dwelling: cuckoo clock, microwave, fridge, drop-down bed and dingy shower. It also has a wall covered in drawings and a curtained screen with the word "Ballyturk" in neon revealed at precisely the same moment each day. There are faces drawn on the screen and, as names are called to fit them, 1 or 2 aims darts at them.  Cillian Murphy plays 1 and Mikel Murfi 2. Murphy has a small frame and an angelic face which can sometimes take on a sinister aspect: in BBC 2's Peaky Blinders his knife-blade cheek bones rival the lethal razor blade in his cap and his piercing blue eyes might dazzle an opponent to death. Here he is fearful, given to fits and manic. Equally frenetic is Mikel Murfi (pictured right), chunkier, red-haired and able to inhabit dozens of characters in an instant by swiftly adapting his body in a sequence of mimes. Both actors fling themselves about the stage under Walsh's own demanding direction. The physical comedy, involving changes of clothes, balloons, loud music, dancing, an alarm clock and various furnishings, is wild, fast, often hilarious and sometimes melancholy, recalling Keaton's sad-eyed, zany purposefulness.

Cillian Murphy plays 1 and Mikel Murfi 2. Murphy has a small frame and an angelic face which can sometimes take on a sinister aspect: in BBC 2's Peaky Blinders his knife-blade cheek bones rival the lethal razor blade in his cap and his piercing blue eyes might dazzle an opponent to death. Here he is fearful, given to fits and manic. Equally frenetic is Mikel Murfi (pictured right), chunkier, red-haired and able to inhabit dozens of characters in an instant by swiftly adapting his body in a sequence of mimes. Both actors fling themselves about the stage under Walsh's own demanding direction. The physical comedy, involving changes of clothes, balloons, loud music, dancing, an alarm clock and various furnishings, is wild, fast, often hilarious and sometimes melancholy, recalling Keaton's sad-eyed, zany purposefulness.

Whether Ballyturk is a real place to 1 and 2, whether the characters impersonated by the pair are figments of their imagination, whether the whole idea of a community is notional – all these are open to question. All we know for sure is that these two are together and that they have a ritual, interdependent existence and occasionally hear other voices beyond their walls. Day follows day according to a pattern, although there is also a sense that they don't quite know what might happen next. Above all, they are friends. Then: Enter 3.

Stephen Rea plays 3, a cooler, cigarette-smoking talker. He might be a version of the Grim Reaper; some have described him as the Godot who did show up. Whoever he is, he disrupts the status quo as, in drama, the unexpected visitor always will.

Like Misterman, Walsh's previous play starring Cillian Murphy at the National, this is a Landmark Production which began life at the Galway Festival. Once again Jamie Vartan and Adam Silverman are responsible for spot-on design and lighting respectively. Helen Atkinson as sound designer and composer Teho Teardo provide an atmospheric, sometimes disturbing soundscape. All the actors are superb.

Despite his venture into musicals with Once, Enda Walsh retains his ability to unsettle, to place side by side daft slapstick, playful theatricality and sublime poetry. As Stephen Rea has said of Ballyturk: "It isn't about something; it is something."

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment