The Great War in Portraits, National Portrait Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

The Great War in Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

The Great War in Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

A cleverly curated and incisive exhibition commemorating World War One

Telling a story through an exhibition can be a bad idea, partly because it seems a little pedestrian but mainly because it runs the risk of using art as illustration, glibly treating paintings as if they were objective visual records. In its title, The Great War in Portraits makes very plain its use of portraiture as a lens through which to view this earth-shattering conflict, but any anxieties about its handling of such a tricky approach are quickly assuaged.

The exhibition begins with Jacob Epstein’s Torso in Metal from The Rock Drill, 1915-16 (pictured right), a sculpture that still shocks a century after it was made. It was originally a much bigger object with a body mounted onto a pneumatic drill so massive that the faceless, humanoid figure astride it seemed to be less in control of the drill than as an appendage attached to it. Epstein described it as the "armed, sinister figure of today and tomorrow. No humanity, only the terrible Frankenstein’s monster we have made ourselves into." The drill was removed in 1916, and the figure was reduced to a head and torso with one arm, a change that was apparently made in response to the unfolding horrors of the conflict, and in hindsight Epstein’s actions seem to mirror changing public perceptions of the First World War with uncanny acuity. On its own, isolated and somewhat cocooned from the rest of the show, the much diminished The Rock Drill is no longer a chilling harbinger of war, and is instead small and unthreatening, a victim not an aggressor. Somehow, with all its contrasts and contradictions it serves as a fitting manifesto for this small but incisive show.

The exhibition begins with Jacob Epstein’s Torso in Metal from The Rock Drill, 1915-16 (pictured right), a sculpture that still shocks a century after it was made. It was originally a much bigger object with a body mounted onto a pneumatic drill so massive that the faceless, humanoid figure astride it seemed to be less in control of the drill than as an appendage attached to it. Epstein described it as the "armed, sinister figure of today and tomorrow. No humanity, only the terrible Frankenstein’s monster we have made ourselves into." The drill was removed in 1916, and the figure was reduced to a head and torso with one arm, a change that was apparently made in response to the unfolding horrors of the conflict, and in hindsight Epstein’s actions seem to mirror changing public perceptions of the First World War with uncanny acuity. On its own, isolated and somewhat cocooned from the rest of the show, the much diminished The Rock Drill is no longer a chilling harbinger of war, and is instead small and unthreatening, a victim not an aggressor. Somehow, with all its contrasts and contradictions it serves as a fitting manifesto for this small but incisive show.

The soldiers’ sunken cheeks, gaping mouths and exhausted poses express a despair as profoundly horrifying as any of the pictures on display

The exhibition is characterised throughout by exceptionally clever curating. A room that sets the scene, giving us an impression of Europe as it was on the eve of war, seems destined to be a pretty boring collection of state portraits, but instead it is a compelling argument that the family alliances that dominated Europe’s ruling élite made large-scale conflict an inevitability. The splendid portraits of Europe’s rulers could not be in greater contrast to the grainy little press photo of the hapless Gavrilo Princip, a man of no consequence, whose assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand turned Europe on its head. By juxtaposing this tatty image with the great portraits of Europe’s leaders, the curators underline the way that this conflict like no other engulfed everyone, from the very privileged to the most ordinary.

From the mass-produced, sentimental postcards depicting soldiers dreaming of home, to the haunting drawings and paintings of official war artist William Orpen, the exhibition does well to cover the great range of image-making generated by the conflict. Orpen’s work features heavily here, and the breadth of his subject matter, from formal portraits like that of a young but careworn Sir Winston Churchill, 1916, to drawings made while wandering the battlefields, suggests not only the vast scope of his brief, but also his own fluctuating view of the war.

Some of Orpen’s most affecting works are little more than sketches and the sparsely detailed background of The Receiving Room: the 42nd Stationary Hospital, 1917 (pictured right), forces our gaze on the agonised figures of three soldiers waiting to be treated. There is no getting away from this picture, which is horribly and quietly naturalistic; the soldiers’ sunken cheeks, gaping mouths and exhausted poses express a despair as profoundly horrifying as any of the pictures on display here.

Some of Orpen’s most affecting works are little more than sketches and the sparsely detailed background of The Receiving Room: the 42nd Stationary Hospital, 1917 (pictured right), forces our gaze on the agonised figures of three soldiers waiting to be treated. There is no getting away from this picture, which is horribly and quietly naturalistic; the soldiers’ sunken cheeks, gaping mouths and exhausted poses express a despair as profoundly horrifying as any of the pictures on display here.

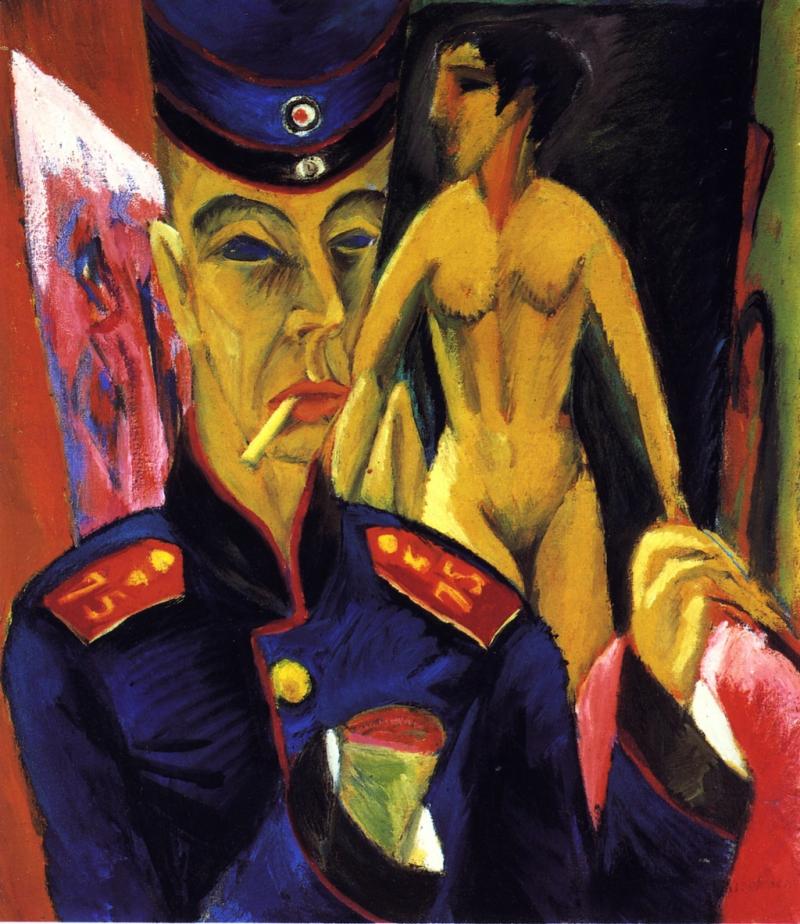

The Official War Artists programme was one way for the government to monitor and control the information that came back from the Fronts, and it is surprising to see how much made it past the censors. Eric Kennington’s devastating painting Gassed and Wounded, 1918 (pictured below) shows a claustrophobic, hellish scene of stretchered casualties, their bandaged eyes the telltale sign of one of the most terrible effects of mustard gas, blindness. The eyes of the orderlies are hidden in shadow too; without eyes, the men appear empty, like husks, as if the War has ripped out the very humanity of its victims.

Appalling as they are, there is a glimmer of hope in a series of images of soldiers undergoing facial reconstruction. A young surgeon, Harold Gillies pioneered plastic surgery as a way of treating the catastrophic effects of gunshot wounds and mustard gas, and drawings and photographs of each patient’s injuries and treatment formed an important part of his medical records. The carefree, boyish face of 2nd Lieutenant RR Lumley shown alongside photographs of his subsequent terrible disfigurement by mustard gas go some way to encapsulating the magnitude of the tragedy inflicted by the War, but the careful, painstaking efforts made to return these men to something of their former selves surely proves that not all humanity was lost.

Appalling as they are, there is a glimmer of hope in a series of images of soldiers undergoing facial reconstruction. A young surgeon, Harold Gillies pioneered plastic surgery as a way of treating the catastrophic effects of gunshot wounds and mustard gas, and drawings and photographs of each patient’s injuries and treatment formed an important part of his medical records. The carefree, boyish face of 2nd Lieutenant RR Lumley shown alongside photographs of his subsequent terrible disfigurement by mustard gas go some way to encapsulating the magnitude of the tragedy inflicted by the War, but the careful, painstaking efforts made to return these men to something of their former selves surely proves that not all humanity was lost.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment