Nile Rodgers: The Hitmaker, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Nile Rodgers: The Hitmaker, BBC Four

Nile Rodgers: The Hitmaker, BBC Four

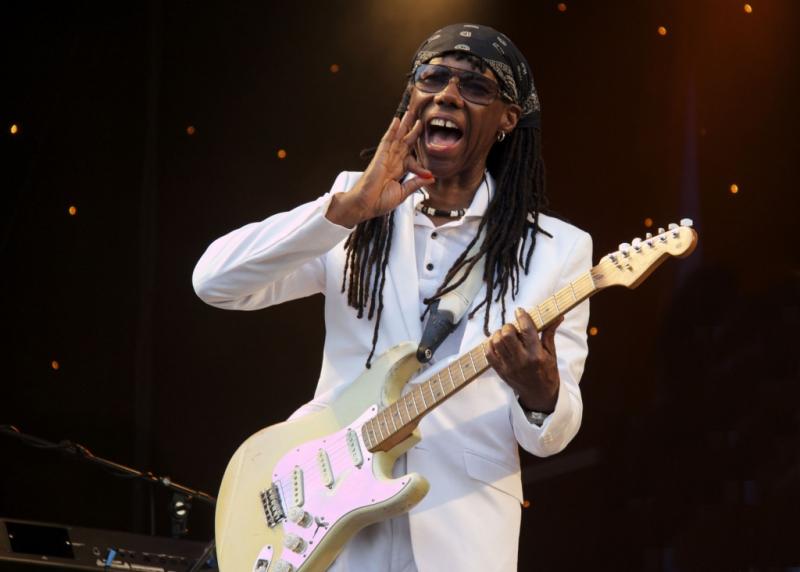

A well-deserved, if workmanlike, appreciation of the great Chic guitarist, producer and songwriter

It was one of those entirely unverifiable "facts" that music documentaries increasingly prefer over genuine insight: early on in this serviceable but routine overview of a truly stellar talent, we were told that Nile Rodgers’s guitar has “played on two billion dollars' worth of hits”. Who really knows? Who actually cares? You don’t measure the sheer joy of Chic’s “Good Times” or Sister Sledge’s “We Are Family” by counting the cash or doing the math. You simply use your ears.

As Johnny Marr pointed out, Rodgers is responsible for countless records “you’d have to be made out of stone not to be moved by”. Marr was just one of several stalwarts lined up to praise the songwriter, producer, arranger and guitarist. Duran Duran's John Taylor, Debbie Harry (saying precisely nothing), and, er, La Roux also appeared, while Bryan Ferry called Rodgers a “genius at improving a song”. The evidence in support was highly persuasive, but most of it came via the music rather than the script.

Bowie wanted a hit; Rodgers wanted some art-rock kudos. Bowie won

Rodgers's unconventional childhood left a mixed legacy. His mother, just 13 when she fell pregnant, and his Jewish step-father were New York beatniks who immersed their son at a young age in literature and modern jazz. They were also heroin addicts who would “fall asleep standing up” and, reckoned Rodgers, left him “wired to be an alcoholic or a drug addict”, a prophecy which had been well and truly fulfilled by the 1980s. By the time Rodgers finally quit cocaine and alcohol in 1994 his heart had stopped on eight separate occasions.

Prodigiously gifted and classically trained, he became a professional guitarist in his teens, first playing with the Sesame Street touring group, before joining the house band at the Harlem Apollo. His meeting with bass player Bernard Edwards in 1973 was the beginning of a partnership that made the pair the Lennon and McCartney of the Studio 54 generation, and their band Chic the disco kings of New York.

Chic's brand of modern, upbeat, repetitive R&B was spare, simple, direct and utterly beautiful. An initial desire for anonymity backfired when they were refused entry to Studio 54 on New Year’s Eve, 1978, despite the fact that inside their songs were filling the dancefloor. Edwards and Rodgers went home to drown their sorrows and wrote an instant riposte called "Fuck Off". It turned into "Le Freak” and sold seven million copies.

After that, they were given carte blanche to start “sprinkling their fairy dust” all over the Atlantic Records roster. They declined the chance to work with The Rolling Stones, believing – correctly – that Jagger and Richards would never give them the control they needed. Instead they turned the little-known Sister Sledge into superstars, writing and producing “We Are Family”, “Lost In Music”, “Thinking of You” and “He’s the Greatest Dancer”. A more thoughtful film would have explored the music in greater depth, and also made more of the fact that these were not just songs of hedonism and escape. They mirrored the sexual agenda of the late 1970s (witness the Rodgers-Edwards penned hit for Diana Ross, “I’m Coming Out”) and, as Rodgers explained, were consciously and cleverly crafted to provide a positive alternative in difficult times.

After that, they were given carte blanche to start “sprinkling their fairy dust” all over the Atlantic Records roster. They declined the chance to work with The Rolling Stones, believing – correctly – that Jagger and Richards would never give them the control they needed. Instead they turned the little-known Sister Sledge into superstars, writing and producing “We Are Family”, “Lost In Music”, “Thinking of You” and “He’s the Greatest Dancer”. A more thoughtful film would have explored the music in greater depth, and also made more of the fact that these were not just songs of hedonism and escape. They mirrored the sexual agenda of the late 1970s (witness the Rodgers-Edwards penned hit for Diana Ross, “I’m Coming Out”) and, as Rodgers explained, were consciously and cleverly crafted to provide a positive alternative in difficult times.

It couldn’t continue. Chic’s next huge hit, “Good Times”, was their last. Suffering from the Disco Sucks backlash, they split in 1983, the same year a chance meeting with David Bowie rejuvenated Rodgers’s fortunes. Bowie wanted a hit; Rodgers wanted some art-rock kudos. Bowie won, but by putting his imprimatur all over the glossy pop-funk of the hugely successful Let’s Dance, Rodgers was back in demand. He went on to “define the sound of pop in the Eighties”, according to John Taylor, who now resembles some weird hybrid of Jim Carrey and Alan Partridge. Rodgers was again a starmaker, producing Madonna’s Like A Virgin, Duran Duran’s Notorious, and working with INXS, Steve Winwood and Ferry. Meanwhile, Chic's bass lines and irrefutable grooves became the bedrock of numerous hip-hop tracks.

The film was slight but warm and well-deserved; and it did tease out the reasons behind Rodgers's success: huge talent, yes, but also unwavering confidence and, above all, an insatiable and truly democratic love of music: he is as likely to draw inspiration from KISS and Roxy Music as classical, R&B or jazz. He’s smart, too, and immensely likeable. Indeed, the film's greatest charm – aside from the soundtrack – turned out to be the engaging presence of the man himself. Whether explaining the essential cultural differences between singing “doo doo doo doo” rather than “la la la la”, or underplaying his recent struggles with an aggressive form of prostate cancer, Rodgers was easy to warm to. Asked about his illness, he said simply: “Every morning I say, ‘Hey, I woke up on this side of the dirt, it’s all cool’.” Long may he stay there.

Watch Chic perform "Good Times" in Japan, Bernard Edwards's final performance before his death in 1996

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Add comment