Darondo and Disco Gold: Unearthed Funk and the Birth of Disco | reviews, news & interviews

Darondo and Disco Gold: Unearthed Funk and the Birth of Disco

Darondo and Disco Gold: Unearthed Funk and the Birth of Disco

Winning comps of music neglected by the mainstream

By 1977, disco was a cliché to be mocked. But a few years earlier, before its ubiquity, disco was a liberating music uniting minorities on the dance floor. Funk, too, became a cliché, little more than a reductive musical cypher. Two new reissues celebrate these genres when both were still vital, still able to surprise.

Disco wasn’t just the place to dance, but the music, too: a synthesis of funk, soul and Latin rhythms that brought the beat to the fore. Manu DiBango’s “Soul Makossa” burst into the US charts in 1973 from New York via Cameroon and Paris. Where the record came from didn’t matter – it was the feel that counted.

Year Zero was 1969, when DJ Francis Grasso began playing records at New York club The Sanctuary, the night spot which filled the space created by the closure of the proto-disco Salvation. Stringing records together, Grasso created a never-ending beat from Aretha Franklin, Booker T and Gladys Knight. He’d sync the drum breaks from Chicago’s “I’m a Man” with the vocal from Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love” for a crowd that was mixed, with a large gay element. Soon, the invitation-only Loft got going, and other clubs followed. At the same time, the string-led Philly sound was cleaning up in the charts. Disco would soon go overground.

Crucial to disco’s increased profile were tracks reconfigured for the dance floor, either sequenced with additional elements (as Grasso had done) or remixed with longer breaks and an increased emphasis on the rhythm. Tom Moulton was central to this new approach. Disco Gold: Scepter Records & The Birth of Disco compiles the best tracks from two albums, Disco Gold and Disco Gold Vol 2, issued by New York’s Scepter label in 1975. Each bore the credits “album mixed and edited by Tom Moulton. A Tom Moulton mix”. In time, Moulton would also pioneer the disco 12-inch.

Crucial to disco’s increased profile were tracks reconfigured for the dance floor, either sequenced with additional elements (as Grasso had done) or remixed with longer breaks and an increased emphasis on the rhythm. Tom Moulton was central to this new approach. Disco Gold: Scepter Records & The Birth of Disco compiles the best tracks from two albums, Disco Gold and Disco Gold Vol 2, issued by New York’s Scepter label in 1975. Each bore the credits “album mixed and edited by Tom Moulton. A Tom Moulton mix”. In time, Moulton would also pioneer the disco 12-inch.

Listen to Patti Jo’s “Ain't No Love Lost” from Disco Gold: Scepter Records & The Birth of Disco

Moulton was a model and regular club-goer at Fire Island, the New York resort. Frustrated with the mood-killing break that came every three minutes when tracks ended, he had the idea of making a mix tape with no breaks between tracks. It took 40 hours to make the first tape. After his tapes caught on, Philadelphia’s studios invited him to mix multi-track masters specifically for the dance floor. Scepter Records then noticed that one of its B-sides, “I Love You, Yes I Do” by The Independents, was climbing the charts with no radio play. Dance floor exposure from Moulton had generated the sales.

Scepter’s Mel Cherin hooked up with Moulton – who’d already been bugging him to release singles solely aimed at the dance floor – and the Disco Gold albums were the result. Disco Gold: Scepter Records & The Birth of Disco joyfully tears through these two records. This isn’t just essential musical history, it’s essential music. Moulton’s mix of “I Love You, Yes I Do” leaves the Philly feel intact, but ramps up the rhythm without undercutting the song. Melody was always central to any potential dance-floor anthem. The South Side Movement’s “Mud Wind” is similarly great, the lack of a vocal line hardly noticeable. George Tindley’s “Pity the Poor Man” could have been a Northern Soul crossover. When Ultra High Frequency declare “We’re on the Right Track”, it’s hard to disagree.

Listen to Bobby Moore's "(Call Me Your) Anything Man" from Disco Gold: Scepter Records & The Birth of Disco

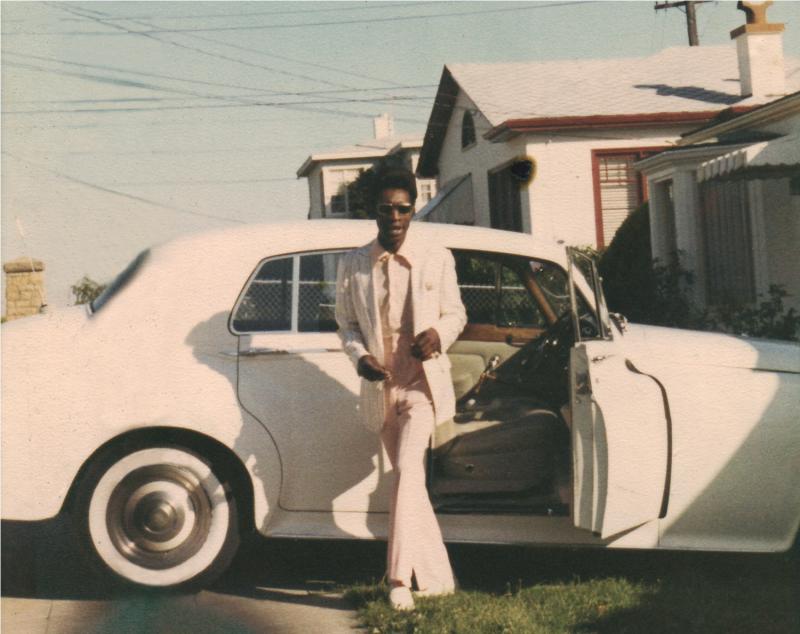

While all this was happening on the East Coast, William Daron Pulliam was trying to get his music career off the ground. From Berkeley, over the bay from San Francisco, he didn’t need big bucks as he’d been investing in property since he was at school and cruised the area in the white Rolls Royce seen above. But music was what drove him. He’d been in the club soul outfit The Witnesses in 1965, and spent a short time working on the railroad. With independent means, he was a regular at clubs in and around San Francisco and hung out with musicians. In 1973 he became Darondo for his debut single “How I Got Over”. It was the first of three. The last was “Legs Pt 1”. All are high-dollar collectables.

Listen to “Didn't I” from Darondo’s Listen to My Song: The Music City Sessions

Between “How I Got Over” and “Legs Pt 1” he attracted the attention of producer Ray Dobard, who owned Music City, the name he used for his pair of record shops, studio and label. Although Music City issued just the one Darondo single – 1973’s “Listen to My Song”/“ Didn't I”, sessions took place in August 1973 and February 1974 for a proposed album. It never came out as Dobard and Darondo acrimoniously fell out. Later, after “Legs Pt 1” failed to make waves, Darondo became a minor celebrity on East Bay cable TV with his mid-Eighties show Darondo's Penthouse. More recently, collectors' interest in his slim discography led to him performing live again. The unreleased Music City album remained in the can, the subject of much speculation.

Watch an excerpt from Darondo's Penthouse, Darondo’s cable TV show

Listen to My Song: The Music City Sessions collects all the material recorded at both sessions. With a sparkling new remix from the master tapes, it’s one of this year's best archive releases. For anyone familiar with the beautiful, Dells-ish “Didn't I”, this CD is going to come as a jolt. The crack and growl of Darondo’s multi-register voice on “Didn't I” is exploited to maximum effect on cuts like “I’m Gonna Love You” and the yearning “Gimme Some”, where he suddenly bounces from one end of the scale to the other. This funk is as much about melody as the groove, and both cuts are as memorable as any Sixties side. Strings and stabbing brass never swamp the voice. This is all about Darondo. Pity it took almost 40 years for this material to come out.

Listen to My Song: The Music City Sessions collects all the material recorded at both sessions. With a sparkling new remix from the master tapes, it’s one of this year's best archive releases. For anyone familiar with the beautiful, Dells-ish “Didn't I”, this CD is going to come as a jolt. The crack and growl of Darondo’s multi-register voice on “Didn't I” is exploited to maximum effect on cuts like “I’m Gonna Love You” and the yearning “Gimme Some”, where he suddenly bounces from one end of the scale to the other. This funk is as much about melody as the groove, and both cuts are as memorable as any Sixties side. Strings and stabbing brass never swamp the voice. This is all about Darondo. Pity it took almost 40 years for this material to come out.

In their own way, each of these CDs is an eye-opener. Disco Gold: Scepter Records & The Birth of Disco washes away the taste of what disco came to mean. Darondo’s Listen to My Song: The Music City Sessions showcases a what if. What if Darondo had issued an album in 1974? Could he have become the soul star he was naturally cut out to be? For now though, the question will have to be moot. Decades on, the music itself will have to do.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Add comment