BBC Proms: London Sinfonietta, BBC Singers, Atherton, Cadogan Hall | reviews, news & interviews

BBC Proms: London Sinfonietta, BBC Singers, Atherton, Cadogan Hall

BBC Proms: London Sinfonietta, BBC Singers, Atherton, Cadogan Hall

Davies and Birtwistle slug it out in afternoon Prom

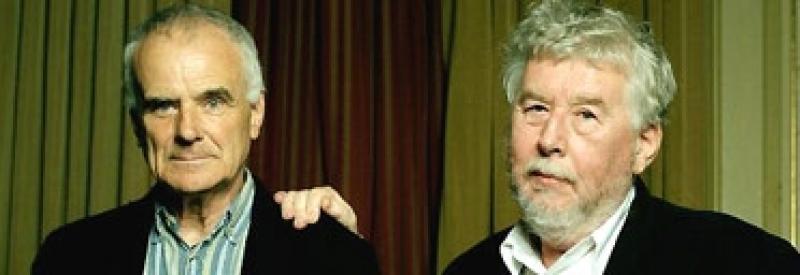

Sirs Harrison Birtwistle and Peter Maxwell Davies have now been at each others’ heels for almost 60 years. First, the composers were students together at the Royal Manchester College of Music. Then, once their careers began flourishing they kept rubbing against each other in concert programmes. Inevitable, really: the same organisations commissioned them; they were the Twin Peaks of British Modernism. Even now, for old times’ sake, the pair can’t escape each others’ shadow.

The difference between the old colleagues’ pieces was immense, though by now not entirely surprising. Birtwistle’s score, graphic in detail, volcanic in force, almost an opera in miniature, hit us straight in the solar plexus. Davies’s motet seemed beautifully intellectual in design, but emotionally remote. Conducted by David Atherton, the BBC Singers’ tenors began with pastiche plainsong, inaugurating five lines of Dante. Then the vocal thread multiplied and tangled to cope with Michelangelo’s sonnet about artistic inspiration: where it comes from, what it leads to. Davies’s construct slimmed down tenderly in the last minutes, leaving us feeling mildly contemplative, suspended in mid-air. All bearable, I suppose, and skilfully sung; though compared, say, to his brilliant student opera Kommilitonen!, premiered at the Royal Academy of Music this March, Il rozzo martello seemed more a commission ticked off than a work PMD had been panting to write.

Birtwistle’s Angel Fighter, though, burst before us, piping hot, jointly forged in the fires of HB’s love of Bach (an influence on its form rather than the style) and his long-standing fascination with myth and primal impulses. It burst out from the performers, too. A veteran of the Leipzig premiere, the incisive tenor Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts relished every pungent word in Stephen Plaice’s libretto as Jacob waited in the desert, moaned about the chorus’s jibes, then faced the higher challenge of an angel of God with a taste for hand-to-hand combat. Angelic counter-tenor Andrew Watts piped most eloquently too.

Bruiser Birtwistle landed many punches of his own, keeping speedy pace with the drama in a score full of baleful writhings (those opening bassoons), forceful arias and choral exchanges, and brilliant sharp edges (the blinding, shrill brass). Reunited with Atherton, their co-founder and first music director, the London Sinfonietta played with terrific panache; while the BBC Singers chipped in vividly as the desert observers, observing events beyond their ken. I had to be carried out on a stretcher.

Any light relief? We came closest with the world premiere of Champ-Contrechamp, a BBC commission from Georges Aperghis, born in Greece but French by adoption and his cultural disposition to the theatrical and absurd. Piano soloist Nicolas Hodges – the piece masquerades as a concerto – supplied an absurd touch himself by arriving in full evening rig, bow-tie, the lot, when all about were hanging loose. With Hodges’ gear you expected Brahms at least; but Aperghis limited the soloist to repeated jabbings and ticklings in a very narrow compass, stopping and starting as the Sinfonietta whirled around and about.

Married to the French film actress Édith Scob, Aperghis has obviously spent much time in the cinema. Hence the work’s title – a reference to the camera shots taken from alternating viewpoints, conventionally used to create dialogue exchanges between two characters. Hodges’ character, the piano, was mostly passive, sometimes aggressive; though charting the work’s ping-pong game quickly proved futile and unnecessary. Had the piece lasted longer than 15 minutes I’d have been driven to distracting thoughts, like whether PMD and HB exchange Christmas cards. But Champ-Contrechamp kept itself brief, tickled the ear, and ended. Bravo.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Add comment