The Hepworth Wakefield | reviews, news & interviews

The Hepworth Wakefield

The Hepworth Wakefield

Yorkshire's new gallery showcases a long tradition of collecting contemporary art

A town in desperate need of regeneration commissions David Chipperfield, the architect of the moment, to build an art gallery in the hope of attracting visitors with deep pockets.

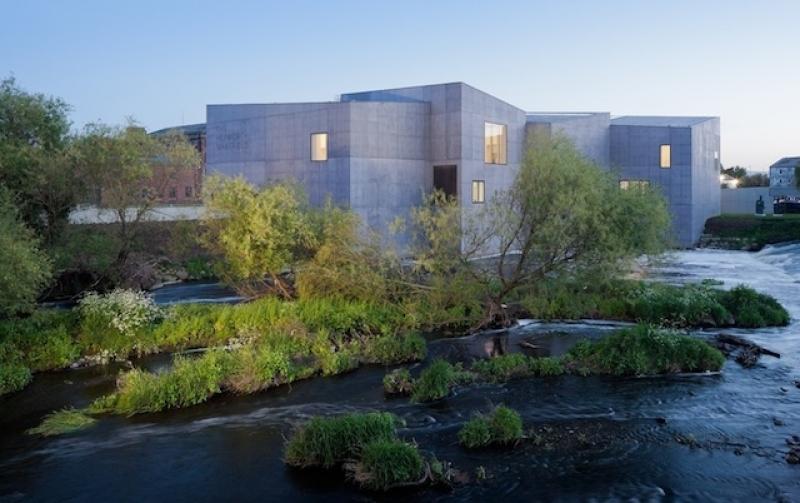

Chipperfield’s style is apparent in both buildings: a series of boxes with sloping rooves stands beside water. But whereas Turner Contemporary doesn’t fully engage with the sea, the Hepworth Wakefield performs a vital function as part of the town’s flood defences, since the River Calder which flows past its walls often breaches its banks.

Coloured pale blue like the sky, the sleek Margate capsule seems to have just landed and is preparing for imminent take-off; made from concrete pigmented with a deep purplish grey, the Wakefield cluster, on the other hand, feels grounded and permanent. And there’s another sense in which the Wakefield building has firmer foundations; having no collection of its own, Turner Contemporary seems like an empty shell, dependent on what it can beg or borrow and vulnerable to the ebb and flow of public opinion. The town of Wakefield, on the other hand, has long boasted an impressive collection of contemporary art.

The original Wakefield Art Gallery opened in 1934 with a remit to "keep in touch with modern art in its relation to modern life". This was surely inspired by the fact that Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore, two of our greatest 20th-century sculptors, came from the area. On August 9th, 1963, under the headline “Henry Packs ‘em in”, the Daily Mirror ran a double spread on the opening of Henry Moore’s exhibition in Wakefield. A wonderful photograph of local housewife, Mrs Elsie Hemmingway peering at an abstract sculpture titled Seated Woman is captioned with her remark: “Well, you can’t get away from it... it's clever."

The original Wakefield Art Gallery opened in 1934 with a remit to "keep in touch with modern art in its relation to modern life". This was surely inspired by the fact that Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore, two of our greatest 20th-century sculptors, came from the area. On August 9th, 1963, under the headline “Henry Packs ‘em in”, the Daily Mirror ran a double spread on the opening of Henry Moore’s exhibition in Wakefield. A wonderful photograph of local housewife, Mrs Elsie Hemmingway peering at an abstract sculpture titled Seated Woman is captioned with her remark: “Well, you can’t get away from it... it's clever."

These pages are on show alongside other memorabilia from the original gallery, which has long since become too small and will be sold now the collection has moved to the new building. These items are on display in its beautiful first floor galleries (pictured above by Peter Macdiarmid). Each room leads into the next. All have sloping ceilings, white walls, pale grey floors and soft light filtered through hidden skylights. Lest it gets too precious, the delicious calm is punctuated by large picture windows that provide dramatic views of the river and neighbouring warehouses. The spaces don’t feel uniform, though; ranging in size from intimate salons showing graphics and archive material to loft-sized spaces perfect for large sculptures, they are full of surprises that make the experience of wandering from one room to another extremely pleasurable.

The building is dedicated to Barbara Hepworth, who was born in Wakefield, and a superb display of her carvings sets the scene. The Cosdon Head, 1949, is one of the most subtly enigmatic of her sculptures. From the back, the smooth lump of dark blue marble looks completely abstract; but running down the front is a ripple carved to evoke the features of a profile. The eyes are suggested by an elliptical hollow on the left side and a sketchy line drawing incised on the right, while the outline of an elegant hand unexpectedly cups an invisible ear. Ranging from illustration to pure abstraction, they offer a witty resumé of the choices open to an artist exploring the language of sculpture at a time when abstraction and figuration were vying for supremacy.

In Hepworth’s case, abstraction won the day. Spring,1966, is a bronze shell hollowed out from both sides until the dividing wall is breached. The interior is coloured pale turquoise and laced with strings that add strength but deny access. Despite its abstraction, one’s experience of the work is enriched by references to natural forms such as eggs, nuts and pebbles and to associations with nurturing, womb-like enclosures.

Hepworth’s heirs have donated a large group of models from which Spring and other bronzes were cast. Most are in plaster, though you wouldn’t always know it since she polished and coloured some to resemble their bronze offspring. Dominating the room (pictured left by Iwan Baan) is the six metre high, aluminium prototype for Winged Figure of 1961 commissioned for John Lewis’s department store; it looks far better in this context than in the traffic laden environment of Oxford Street.

Hepworth’s heirs have donated a large group of models from which Spring and other bronzes were cast. Most are in plaster, though you wouldn’t always know it since she polished and coloured some to resemble their bronze offspring. Dominating the room (pictured left by Iwan Baan) is the six metre high, aluminium prototype for Winged Figure of 1961 commissioned for John Lewis’s department store; it looks far better in this context than in the traffic laden environment of Oxford Street.

A fascinating display of studio paraphanelia provides invaluable insight into the working methods and thought processes that lie behind her seemingly effortless production. It includes chiselling tools, small sculptures by Hepworth and others, including a group of Cycladic dolls, an explanation of the casting process and a maquette of an initial idea for the John Lewis commission of a flying ducks-style trio of ellipses.

While the family’s gift ensures the status of the gallery as a major centre for the study of Hepworth work, loans from the Tate, British Council and Dartington Hall of paintings by Mondrian and sculptures by major figures such as Brancusi and Naum Gabo ensure the gallery’s international significance. They allow Hepworth and other British artists like Henry Moore, Victor Pasmore, Ben Nicholson and Jacob Epstein to be seen in the context of European modernism – as pioneers of the abstraction that was sweeping away figurative art. And the minimalism of Chipperfield’s perfectly tuned design provides the perfect foil for their explorations of pure form.

Eva Rothschild’s acts of homage turn out to be wickedly subversive

To ensure the gallery keeps in touch with recent development and that punters return again and again, the four largest galleries are reserved for temporary exhibitions by contemporary artists. Eva Rothschild rises to the challenge with sculptures that create a witty dialogue between abstraction and figuration. Lying propped against the wall, El Fenix is a shining pool of black resin that lays claim to a rug whose presence is revealed only by the tufts of wool fringing the edges. Coloured green, red and black the angular rods of Stairways are delicately held aloft by six tiny black hands attached to the walls and ceiling. Sunrise performs one of Rothschild’s favourite tricks; the large hoop appears to levitate when, in fact, it is secretly held aloft by the red ribbons hanging from its rim.

Perforated ellipses such as Dr. Nut and Horn of Plenty (pictured right by Jerry Hardman-Jones) self evidently paraphrase Hepworth’s work, but these acts of homage turn out to be wickedly subversive. In their wobbly playfulness, the sculptures seem to embrace frailty, error and incompetence – signs of the weakness and entropy that modernists sought to overcome with their idealistic belief in the improving power of good design.

Perforated ellipses such as Dr. Nut and Horn of Plenty (pictured right by Jerry Hardman-Jones) self evidently paraphrase Hepworth’s work, but these acts of homage turn out to be wickedly subversive. In their wobbly playfulness, the sculptures seem to embrace frailty, error and incompetence – signs of the weakness and entropy that modernists sought to overcome with their idealistic belief in the improving power of good design.

The Hepworth Wakefield is not the only cultural attraction in the area. The Yorkshire Sculpture Park is only a 15 minute drive away and the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds is a few miles down the line; so visitors can spend a weekend exploring contemporary art in the area.

The gallery is just one of many initiatives instigated by Wakefield’s enlightened council to kick start the local economy. There’s a new market hall designed by David Adjaye and the gallery has commissioned a bespoke beer from West Yorkshire’s Ossett Brewery; the beer mats proclaim “There’s something creative brewing in Wakefield”. The leader of the council is Peter Box; his enthusiastic support has been crucial to the success of this ambitious project and, you’ve guessed it, the locals have nicknamed the new building Peter’s Box. It’s a sure sign that the Hepworth Wakefield will be a success.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment