A Midsummer Night's Dream, English National Opera | reviews, news & interviews

A Midsummer Night's Dream, English National Opera

A Midsummer Night's Dream, English National Opera

Britten's worst nightmares realised in rigorous schoolhouse production

Just think, said a veteran enthusiast of Britten's operas when I showed him the earliest publicity designs for Christopher Alden's production, you could set them all in a school, even Gloriana - what about headmistress Bess and head prefect Essex? But could you squidge everything into the one shape, I wondered?

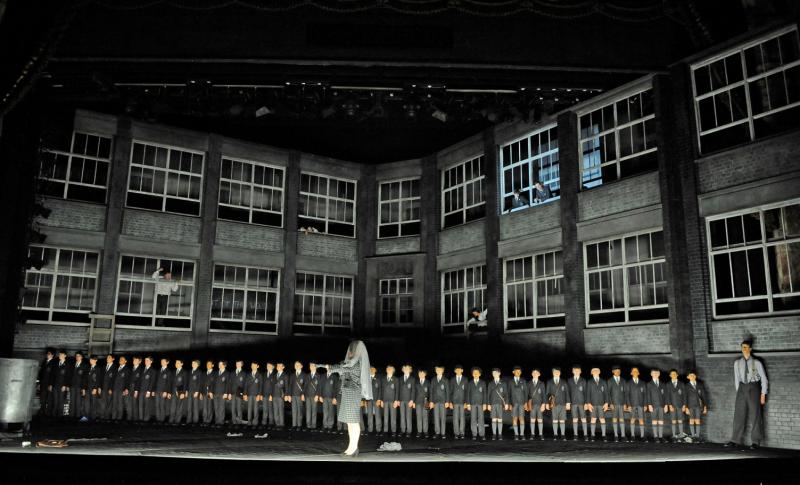

Yes it can, at least in this Alden brother's hands, and with a grim rigour that set some of us reeling from the parallel universe we'd been compelled to join, others - a critic or two among them, I later learnt, shame on the whole pack - booing loudly, presumably at the putative violation of composer's and playwright's more innocent visions. Violation there certainly is, a deliberate going against the grain of what idylls Britten seems, consciously at least, to have intended in a general drama of strangeness - chiefly Tytania's infatuation with translated Bottom (no midsummer sweetness, no ass's head here) and what's usually the poignant reconciliation of fairy and mortal worlds in the Scots-snap finale, concluded here with a bitterly sarcastic slow handclap. But for the first time I heard far more of the feral, jarring notes in the often bony score, and that has to do not only with the hard light that Alden's production, Charles Edwards's surprisingly adaptable school-block design and Adam Silverman's lighting shine on it, but also a knife-edge complementary vision from Leo Hussain conducting the ENO Orchestra.

Once you've accepted that you're not going to see the wood for the school, anything goes. The stark, grey facade works well with the sighing, groaning string glissandi that come from somewhere deep in the forest of Britten's own dream-world, as an old boy (a not always explicably anguished Paul Whelan, only to be revealed as Britten's Theseus two-thirds of the way through the action) conjures up his stricken younger self, an astonishing, angry performance by Jamie Manton. Zombie schoolboys of the late 1950s or early Sixties - the time of the opera's composition - line the glassless window frames: these are our fairies, a far cry from the Kensington WH Auden so loathed about the first performance.

It's not until the trumpet and drum rattle an acrobatic routine that's never going to be danced to here and the sullen teenager speaks his lines in a sour, cracked voice that you realise this is our Puck, and his master Oberon is the bespectacled schoolmaster at the blackboard (correction time for "this is thy negligence" pictured right, with Dominic Williams's "changeling boy" looking on). It was essential on the first night that the stylish Iestyn Davies, suffering from a throat infection and unable to call upon his similarly stricken understudy - another, extremely promising countertenor Iestyn - should go convincingly through the motions while William Towers, called up from Glyndebourne, did a wonderful job from a box at the side of the stage. We know the magic Davies can conjure, but it couldn't have surpassed every colour and inflection Towers brought to bear on the great Purcell-style solo of "I know a bank". Huge kudos to both for saving the integrity of the show.

It's not until the trumpet and drum rattle an acrobatic routine that's never going to be danced to here and the sullen teenager speaks his lines in a sour, cracked voice that you realise this is our Puck, and his master Oberon is the bespectacled schoolmaster at the blackboard (correction time for "this is thy negligence" pictured right, with Dominic Williams's "changeling boy" looking on). It was essential on the first night that the stylish Iestyn Davies, suffering from a throat infection and unable to call upon his similarly stricken understudy - another, extremely promising countertenor Iestyn - should go convincingly through the motions while William Towers, called up from Glyndebourne, did a wonderful job from a box at the side of the stage. We know the magic Davies can conjure, but it couldn't have surpassed every colour and inflection Towers brought to bear on the great Purcell-style solo of "I know a bank". Huge kudos to both for saving the integrity of the show.

But what were we watching here - Oberon and Tytania quarrelling over a little changeling boy, or ghostly Peter Quint and the Governess struggling for the soul of little master Miles in The Turn of the Screw? The parallel is perfectly apt, because Oberon's spectral music also carries the queasy colour of the celesta: he, too, is "all things strange and bold", and even just as an acted performance, Davies's managed to capture something of the threatening appeal behind the schoolmasterly repression. All this, it's not too implausible to believe, ran deep with Britten; in his comprehensive interviews with folk who knew the composer for his major biography, Humphrey Carpenter called upon librettist Eric Crozier to witness that Britten told him he'd been raped by a master at school. Fantasy or truth? We'll never know, but there it is, it won't go away and it would certainly account for the more subcutaneous utterances of this tortured genius. John Bridcut, who contributes a typically sensitive note to the programme, has also made a finely nuanced documentary and written a lucid book on Britten's complex relationship to childhood, and why it matters to his music.

Yet it would be reductive to make A Midsummer Night's Dream just about this, and the aura of abuse, if not the lifelong misery it causes, is in any case kept as intangible and threatening as it is in The Turn of the Screw. The sexual fantasies and confusions of adolescents are everywhere, once-straitjacketed feelings are released by puffing on the "weed" that serves as Alden's magic juice. There's the fumbling, pansexual heat of the mixed-up sixth form lovers - Allan Clayton ringing of tenor tone as a bumbling, bookish Lysander despite advertised ill health, the girls (Tamara Gura and Kate Valentine) less clear diction-wise than their ENO predecessors in the beautiful, bed-ridden Robert Carsen Dream.

And of course there's Alden's deliberately against-the-grain handling of the Tytania-Bottom encounter. Puck-become-Theseus's part in it, trapped in a red-lit bondage inferno that's never naff or crudely sensationalised, isn't quite clear; but Anna Christy, vocally too much of a pipsqueak coloratura to convey the measured sensuousness of the Fairy Queen, acts out her spliff-liberated violence with grim relish. And Sir Willard White (pictured above left with Christy) may not care at first to relish the misappropriated words of basement-dwelling weaver/caretaker Bottom, but he's game, and still in good shape both vocally and physically, for the sexual shenanigans of the nightmare.

And of course there's Alden's deliberately against-the-grain handling of the Tytania-Bottom encounter. Puck-become-Theseus's part in it, trapped in a red-lit bondage inferno that's never naff or crudely sensationalised, isn't quite clear; but Anna Christy, vocally too much of a pipsqueak coloratura to convey the measured sensuousness of the Fairy Queen, acts out her spliff-liberated violence with grim relish. And Sir Willard White (pictured above left with Christy) may not care at first to relish the misappropriated words of basement-dwelling weaver/caretaker Bottom, but he's game, and still in good shape both vocally and physically, for the sexual shenanigans of the nightmare.

There's a real coup here in de-twee-ifying the "fairies" and their role in the musical idyll. The kids have broken out, in the dream at least, with fags and shades; the piping recorder and homely percussion music that entertains Bottom becomes a terrifying orgy of rapping, stomping, window-rattling sound. It well prepares us for the eruption of greater violence later in the act. For the second time in just under a fortnight, I'm not going to spoil the shock of a visual coup, but this is where Edwards, Alden and Silverman really come together at their best. And this is a more consistently realised show than Gilliam's fitfully brilliant Damnation of Faust.

The fug of the nightmare gives way to a frozen tableau as Act III supposedly unravels the confusion. Each group is unbound - Davies and Christy winding their way in slow-motion ballroom dance up the school-block stairs, the lovers making beautiful work of their ecstatic quartet - and the difficult transition to the daylight world of Theseus and Hippolyta's wedding is superbly made. The very lamentable comedy of Pyramus and Thisbe brings belly laughs, but the kind that quickly freeze. We're now in a riotous red-and-yellow world of amateur theatrics with Annigoni's 1956 Queen looking on (pictured above right). Up Pompeii! meets Carry On, but with the repressed libido of all those No Sex Please We're British innuendos released. So repulsive, inebriated, pissing and vomiting Snout as Wall (Peter Van Hulle) actually shouts another line not in the original Shakespeare; Britten and Pears added only one, "compelling thee to marry with Demetrius", but here the tittering audience of lovers in a box are told to "fuck off!" too.

The fug of the nightmare gives way to a frozen tableau as Act III supposedly unravels the confusion. Each group is unbound - Davies and Christy winding their way in slow-motion ballroom dance up the school-block stairs, the lovers making beautiful work of their ecstatic quartet - and the difficult transition to the daylight world of Theseus and Hippolyta's wedding is superbly made. The very lamentable comedy of Pyramus and Thisbe brings belly laughs, but the kind that quickly freeze. We're now in a riotous red-and-yellow world of amateur theatrics with Annigoni's 1956 Queen looking on (pictured above right). Up Pompeii! meets Carry On, but with the repressed libido of all those No Sex Please We're British innuendos released. So repulsive, inebriated, pissing and vomiting Snout as Wall (Peter Van Hulle) actually shouts another line not in the original Shakespeare; Britten and Pears added only one, "compelling thee to marry with Demetrius", but here the tittering audience of lovers in a box are told to "fuck off!" too.

There's lots of mooning from Simon Butteriss's Starveling, the most consistently funny of the mechanicals in his green tights, and thigh-flashing from Michael Colvin's excellent Flute as Thisbe, but her passion ends the play rather darkly as Puck pops up again to propose our mock-Lucia finish herself off. The trauma is bound to return, and in one final touch of perverse magic, the most innocently beautiful of all Britten's operatic resolutions, "Now until the break of day", works brilliantly within the tension of Alden's context. Did I have uneasy dreams about it? Of course.

- Find Overture Opera Guide to A Midsummer Night's Dream (including an article on production history by David Nice on Amazon

- See what's on at English National Opera. Read ENO reviews.

Watch snippets of a very different staging accompanied by "Now until the break of day" in Baz Luhrmann's legendary Raj-set Opera Australia production

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Add comment