Who's afraid of Edward Albee? | reviews, news & interviews

Who's afraid of Edward Albee?

Who's afraid of Edward Albee?

Remembering the playwright who fearlessly looked under the surface of the American Dream

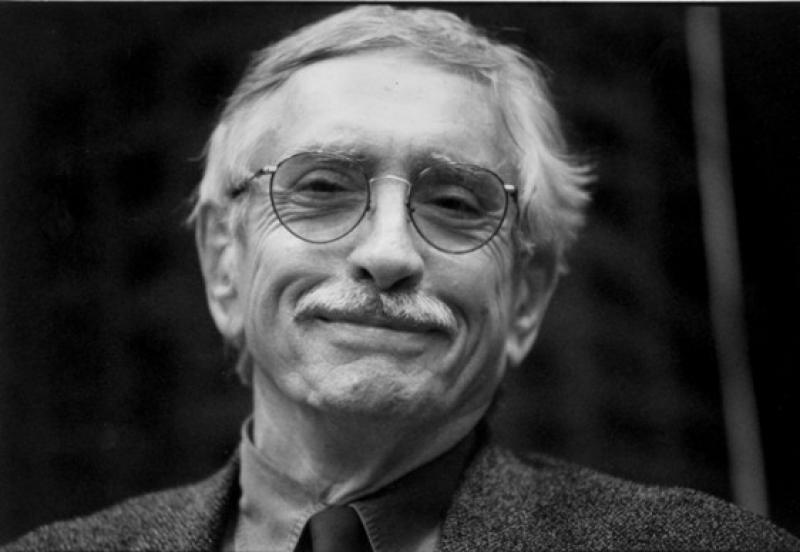

"I've always thought there's nothing worse than coming to the end of your life and realising that you haven't participated in it, and so I write about people who've done that to a certain extent." Edward Albee has died at the age of 88, having participated in his life far more actively than George and Martha, the couple in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? whose idea of hell is each other.

His best-known plays had the civilised exterior of East Coast comfort: there were no Eddie Carbones in his world view, only profs and tennis club habitués and well-heeled products of the WASP factory. But open the front door and all you can see is rage and cruelty and slurping alcoholism.

Albee took a bleak view of matrimony thanks to his loveless upbringing as the adopted only child of a wealthy New York theatre owner and his third wife, from whom he made good his escape in his late teens. He anatomised the baroque dynamics of heterosexual marriage with the detached curiosity of someone who spent several decades in a relationship with another man.

He began writing plays early. "I had written a three-act sex farce when I was 12," he told me when I first interviewed him in 1997. "There were a couple of half-assed attempts at writing plays in my early twenties which I didn't finish. I was a lousy novelist and a not very good poet. I wasn't ready to be a playwright until I was 30." That was the age, he said, at which he realised he was going to die. “If you're aware of that then you certainly know that you're supposed to live more fully."

His first play, The Zoo Story, was premiered in West Berlin in 1959, and was first seen in New York the following year in a double bill with Krapp's Last Tape. "There was no off-Broadway and no one wanted an hour-long grumpy play by an unknown American on Broadway." He quit delivering telegrams for Western Union, and within three years had written Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, ensuring that, however unhip, he would never be unknown again. (Pictured above, Kathleen Turner and Bill Irwin as Martha and George.) When John Steinbeck was sent on a friendship mission to the Soviet Union in 1963, he insisted on taking Albee with him, who was thus in Poland when the President was assassinated. (Steinbeck is the dedicatee of his next most performed play, A Delicate Balance.)

His first play, The Zoo Story, was premiered in West Berlin in 1959, and was first seen in New York the following year in a double bill with Krapp's Last Tape. "There was no off-Broadway and no one wanted an hour-long grumpy play by an unknown American on Broadway." He quit delivering telegrams for Western Union, and within three years had written Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, ensuring that, however unhip, he would never be unknown again. (Pictured above, Kathleen Turner and Bill Irwin as Martha and George.) When John Steinbeck was sent on a friendship mission to the Soviet Union in 1963, he insisted on taking Albee with him, who was thus in Poland when the President was assassinated. (Steinbeck is the dedicatee of his next most performed play, A Delicate Balance.)

A Delicate Balance, premiered on Broadway in 1966, won Albee the first of his three Pulitzer Prizes (Who's Afraid was denied it by the judging committe for being too frank about adultery and using profane language). It ruthlessly holding up a mirror to the predominantly middle-class audiences who flocked to see it. It tells of a wealthy suburban couple whose smoothly oiled marriage is at odds with mental instability, alcoholism and nameless paranoia of their closest family and friends. It was another coded attack on the WASPs among whom he'd grown up.

Albee protected these most performed of his works zealously. He would go on to see more than 100 different productions of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. He withdrew the rights to a production in Mexico when he heard they'd shortened it. He obliged a mid-1990s production of A Delicate Balance to change the set. "It was Bauhaus. I looked at it and said, 'It's absolutely perfect. There's only one trouble.' 'What's that?' 'Those people couldn't live there.'" He made it fairly obvious that he "loathed" John Napier's design for the Almeida production of Who's Afraid starring David Suchet and Diana Rigg. "There was so much fucking carpentry and machinery backstage. You couldn't cross the stage behind, and I thought that was terrible. There is a thing about British set design: it's always calling attention to itself. I hate sets that make psychological or symbolic comments."

He was not the easiest playwright to interview. His answers could be unnervingly short, as if in his own certainty he has no need of prolixity. And when they stretched their legs and wandered about a bit, they seemed to be using their length to crush the crassness out of the question. You could usually tell you'd been doltish when the first word of his answer was "probably". As in, how do the ideas make their way into his head in the first place? "Probably because I'm a writer. And they're plays rather than novels because I am a playwright." Or why did Three Tall Women, the first Albee play ever to earn unanimous critical approval (pictured above: Samantha Bond, Sara Kestelman and Maggie Smith), open in the New York equivalent of the Almeida? "Probably because Broadway management thought it was too - what's that terrible word? - dark. And also no chandeliers crashed to the floor."

He was not the easiest playwright to interview. His answers could be unnervingly short, as if in his own certainty he has no need of prolixity. And when they stretched their legs and wandered about a bit, they seemed to be using their length to crush the crassness out of the question. You could usually tell you'd been doltish when the first word of his answer was "probably". As in, how do the ideas make their way into his head in the first place? "Probably because I'm a writer. And they're plays rather than novels because I am a playwright." Or why did Three Tall Women, the first Albee play ever to earn unanimous critical approval (pictured above: Samantha Bond, Sara Kestelman and Maggie Smith), open in the New York equivalent of the Almeida? "Probably because Broadway management thought it was too - what's that terrible word? - dark. And also no chandeliers crashed to the floor."

While George and Martha travelled the world, he went through a period when New York producers wouldn’t touch him with a bargepole. The painfully nihilistic The Lady from Dubuque closed after 12 performances when premiered in New York in 1980. “It’s called the critical fallacy,” Albee told me. “If the critics don’t like it, it means it’s not good. I thought some of the criticism was not only hostile but stupid.” (The critics had mostly not been won round when in 2003 the West End revival yielded the odd sight of Dame Maggie Smith, national treasure, box-office royalty and regular Albee muse, playing to an empty circle.)

Despite the safety-first policy on Broadway, in 1990 Three Tall Women Off Broadway rescued its author from the slough of commercial despond. Not that he quite saw it that way. "All that time, a 10- or 12-year period when I wasn't ever put on in New York or London, I had lots of plays in the rest of Europe, around the United States, Latin America, just not New York City. But everybody in the theatre in America thinks New York City is the centre of the universe." Meanwhile, various new plays continued to attract the attention of audiences, notably The Play About the Baby (1996) and The Goat, or Who is Sylvia? (2002), Albee’s allegorical depiction of an architect’s extramarital hankering for a farmyard animal.

There were 32 plays in the end, including adaptations of Carson McCullers’ The Ballad of the Sad Café, Nabokov’s Lolita and Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s. His final play was Me Myself and I (2007), a typically contorted view of family dynamics in which a mother has trouble telling her twin sons apart partly because she has named them OTTO and otto.

There was one short experimental play Albee never wrote but which rattled around in his head anyway. Into it he planned to cram all his abhorrence of egotistical directors interfering with the rhythm of his dialogue. The actors would speak at the behest of an actual conductor. “If it’s written properly,” he told me, “there will be a proper relationship between what is conducted and how the actors naturally speak the lines.”

Directors and critics were not the only part of theatre’s ecology for whom Albee struggled to put together two good words. He wasn’t that keen on audiences, "trained to want less, to be satisfied with less". Nor playwrights "who go on writing plays who haven't got an idea in their head".

This last, of course, never happened to Albee. "When I have no ideas for plays,” he said, “I hope I'll have the sense not to try to write them."

Edward Albee, 1928-2016

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Add comment