Imagine: The Trouble with Tolstoy, BBC One | reviews, news & interviews

Imagine: The Trouble with Tolstoy, BBC One

Imagine: The Trouble with Tolstoy, BBC One

Scrupulous documentary enlightens even the crankier aspects of literature's God

Trouble? What trouble? There may be the odd reader who doesn't get past the Austerlitz sequence of War and Peace, and many who don't brave the master's last big novel questioning church and state, Resurrection, but that's their problem, not Tolstoy's. He is indeed - as Professor Anthony Briggs, the other star of this two-part documentary, states - the God of the novel. As a man, he was troubled to his dying day, and eventually a trouble to the state.

The chief virtue of Rupert Edwards's work is to illustrate how big a part Tolstoy plays in many people's - certainly many Russians' - lives today. "We need to look at our life now through the eyes of Tolstoy," is the emphatic proclamation of Professor Elvira Osipova. Novelist Boris Akunin is more playful about his 11-year-old self reading War and Peace - or at least the battle scenes - before going on to tell us that its loveable leading trio of Natasha Rostova, Andrey Bolkonsky and Pierre Bezukhov are "more alive for me today than a lot of people... whom I know personally". Alliluya to that.

In practical terms, we see the many descendants of Tolstoy through the eight of his 13 children who survived gathering at the family estate of Yasnaya Polyana, hear great-great-grandson Vladimir Tolstoy tell us how the Patriarch under Putin still fails to respond to pleas to lift the novelist's belated excommunication, watch Yentob drink kumiss or fermented mare's milk, as did Tolstoy for a cure, in the steppe outside Samara (or "Thamara" as our presenter first calls it - and this sequence is the only one which made me expostulate wearily at the TV), and watch a descendant of the Dukhobors, the pacifistic religious group which Tolstoy paid to emigrate to Canada, return to the estate. (Tom Birchenough, fixer and researcher on this documentary, gives further flavour in a feature on last year's "lost centenary".)

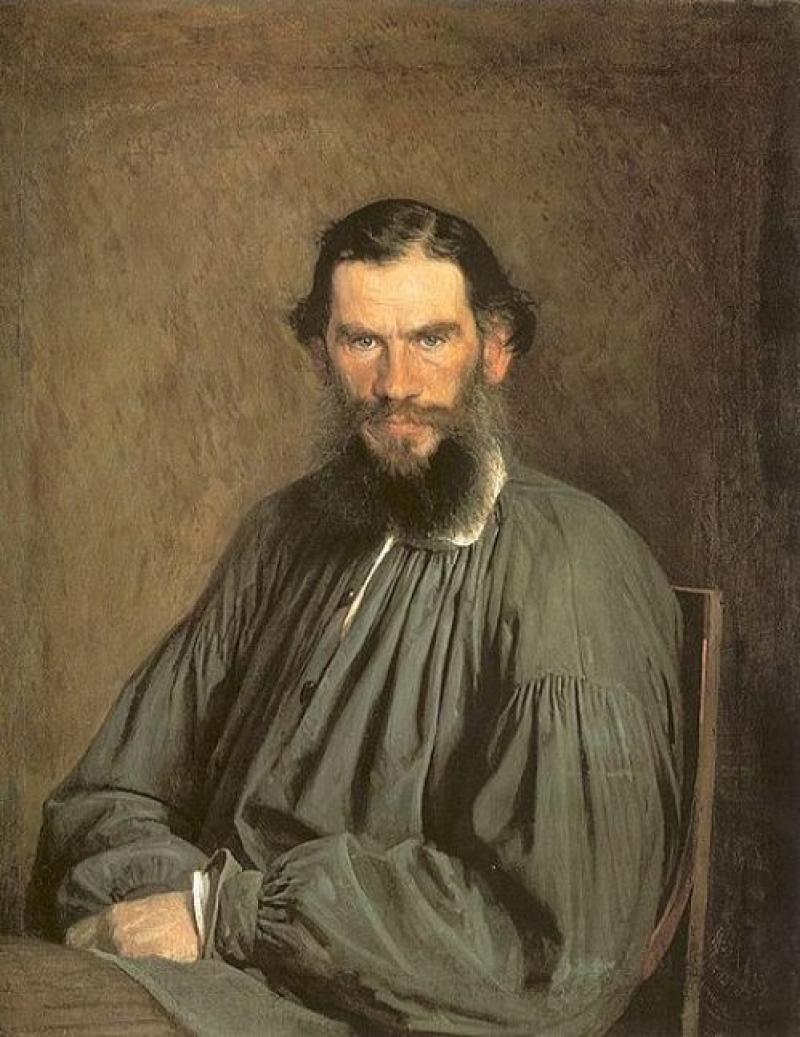

And always chief cameraman Andrey Erastov is catching the Russians, Tatars and Ukrainians of today in magical lights, poetically underlining the continuity of the superbly nuanced readings by Rory Kinnear, David Calder and Deborah Findlay. We listen with amusement as the young Tolstoy (pictured right in 1848), sent to study at Kazan University after losing his parents at an early age, resolves to "carry out" a vast, impossible programme of self-teaching, only to note "I haven't carried out this resolution" - a Sisyphean aspect of his nature which, Yentob wryly remarks, is still dogging the later self-examination. We hear powerful extracts from his first and second Sebastopol sketches, written during his first military posting proper in the Crimean War and moving from patriotic support of the Tsar's war effort to a sense of the pointlessness of it all. In War and Peace we get the crucial moment at the Battle of Borodino where Nicolai Rostov becomes "depressed, vague and confused" at the look of helplessness on a captured French officer's face.

And always chief cameraman Andrey Erastov is catching the Russians, Tatars and Ukrainians of today in magical lights, poetically underlining the continuity of the superbly nuanced readings by Rory Kinnear, David Calder and Deborah Findlay. We listen with amusement as the young Tolstoy (pictured right in 1848), sent to study at Kazan University after losing his parents at an early age, resolves to "carry out" a vast, impossible programme of self-teaching, only to note "I haven't carried out this resolution" - a Sisyphean aspect of his nature which, Yentob wryly remarks, is still dogging the later self-examination. We hear powerful extracts from his first and second Sebastopol sketches, written during his first military posting proper in the Crimean War and moving from patriotic support of the Tsar's war effort to a sense of the pointlessness of it all. In War and Peace we get the crucial moment at the Battle of Borodino where Nicolai Rostov becomes "depressed, vague and confused" at the look of helplessness on a captured French officer's face.

Excerpts in the second part of the documentary are equally tellingly chosen. I'd forgotten that it was as much in the character of long-suffering wife and mother Dolly in Anna Karenina as in its portrait of the young Kitty that Tolstoy sympathised, as perhaps he never properly did in life, with his own Countess Sofia - a stunning passage captures all the weariness of childbirth and the grief of child-loss. And the painful loss of love and respect between the Tolstoys is hauntingly captured in Sofia's diaries, registering the descent into a kind of Strindbergian hell which would have made an equally haunting novel (something of its disgust came out in the shocking novella The Kreutzer Sonata, not mentioned here).

The unhappy tale of the last years (pictured left, original colour photograph of Tolstoy in 1908) gets perhaps a disproportionate share in part two, but given the surprising amount of archive film and documentary evidence, that's not surprising. I found myself sympathetic for the first time to aspects of Tolstoy's supposed religious fanaticism, not least in the face of such creepy Russian Orthodox opponents as the still-resentful, censorious Father Selophil of the Optina Pustina monastery which played such a part in Tolstoy's religious development. His deviation seems not so much the madness of old age as a furious disenchantment with the heavy apparatus of state; you can see why he became a hero to the thousands of non-novel-reading Russians who gathered at his funeral and stirred up further revolutionary discontent post-1905. The Dukhobors don't seem so obsessive, either, though there remains the question mark of Vladimir Chertkov, great love of Tolstoy's old age - in what sense, it's never made quite clear, and surely the homoerotic aspect isn't as impossible as Professor Briggs asserts - bringing trouble and quarrels in his wake.

The unhappy tale of the last years (pictured left, original colour photograph of Tolstoy in 1908) gets perhaps a disproportionate share in part two, but given the surprising amount of archive film and documentary evidence, that's not surprising. I found myself sympathetic for the first time to aspects of Tolstoy's supposed religious fanaticism, not least in the face of such creepy Russian Orthodox opponents as the still-resentful, censorious Father Selophil of the Optina Pustina monastery which played such a part in Tolstoy's religious development. His deviation seems not so much the madness of old age as a furious disenchantment with the heavy apparatus of state; you can see why he became a hero to the thousands of non-novel-reading Russians who gathered at his funeral and stirred up further revolutionary discontent post-1905. The Dukhobors don't seem so obsessive, either, though there remains the question mark of Vladimir Chertkov, great love of Tolstoy's old age - in what sense, it's never made quite clear, and surely the homoerotic aspect isn't as impossible as Professor Briggs asserts - bringing trouble and quarrels in his wake.

And, yes, the well-documented tale of Tolstoy's last flight from the unbearable pressures of both wife and disciple is, as Professor Olga Slivitskaya says, a "King Lear moment, a genuine Shakespearean drama". Astonishing that there should be all that footage of the final crisis as he lay dying in the remote railway officer's house: there's old Sofia hanging around the door, desperate to embrace him one last time before he breathes his last (a request not granted).

The various biographers represented are tough on this complex, tormented man, with the surprising exception of an unusually affectionate AN Wilson. Rosamund Bartlett concentrates on Tolstoy's "narcissism"; Briggs, whose engaging manner and habit of seeming to polish off his vivid sentences on the hoof suggest he should have been our guide throughout, tells us how the great man was "left on a small island of self-righteousness and unrealistic expectations and disappointments. He couldn't love anyone: that's the great tragedy of Tolstoy". Yet how much love there is in his novels. And anyone who can still enrage so many people today, like that other great thinker of the 19th century Charles Darwin, has to be a hero of sorts. He's certainly one of mine, in spite of all the cruelties and weaknesses - or probably, in Tolstoyan terms, because of them.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

Add comment