Mondrian || Nicholson in Parallel, The Courtauld Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Mondrian || Nicholson in Parallel, The Courtauld Gallery

Mondrian || Nicholson in Parallel, The Courtauld Gallery

A compelling conversation between two of the leading forces of abstract art in Thirties Europe

Conversations between artists both verbal and visual are the flavour of the month: the big voice of Picasso is almost but not quite drowning out a septet of British artists over at Tate Britain. Now joining the chorus is a fascinating exploration of the 1930s, in which the Brit Ben Nicholson and his Dutch friend and colleague Piet Mondrian are described by that hotbed of art history, the Courtauld, as "leading forces of abstract art in Europe”.

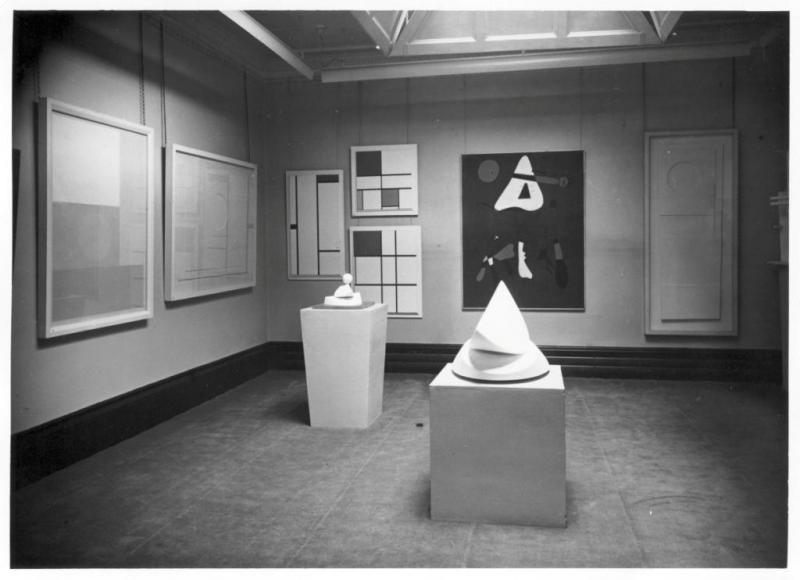

To make the point about both the conversation between Nicholson and Mondrian and the results, the Courtauld has put on a thoughtful, succinct exhibition – the gallery can do in two rooms what for most museums would take ten – based on its own exceptionally agreeable 1937 (painting) by Nicholson (pictured below left). But why does Mondrian have an international reputation as one of the leading painters of the 20th century and Nicholson, over 20 years his junior, a leader only in Britain?

To the visitor the paintings and reliefs seem startlingly different, though the scaffolding can seem touchingly similar. Nicholson’s carved white wooden relief, 1938 (white relief) and Mondrian’s Composition No 1 with Red, 1939, are almost like echo chambers in terms of composition. There is a shared sense of spatial relationships, and a pared down vocabulary of lines, squares, rectangles, no curves from Mondrian, an occasional circle from Nicholson. Mondrian’s Composition B/(No II) with Red, 1936 and Ben Nicholson’s 1936 (white relief) are equally fascinating as a pair, the Mondrian using a square of dazzling red in the top left hand corner, the Nicholson using a carved white circle as the protagonist.

To the visitor the paintings and reliefs seem startlingly different, though the scaffolding can seem touchingly similar. Nicholson’s carved white wooden relief, 1938 (white relief) and Mondrian’s Composition No 1 with Red, 1939, are almost like echo chambers in terms of composition. There is a shared sense of spatial relationships, and a pared down vocabulary of lines, squares, rectangles, no curves from Mondrian, an occasional circle from Nicholson. Mondrian’s Composition B/(No II) with Red, 1936 and Ben Nicholson’s 1936 (white relief) are equally fascinating as a pair, the Mondrian using a square of dazzling red in the top left hand corner, the Nicholson using a carved white circle as the protagonist.

The conversation had been intense. Nicholson, then married to his first wife, Winifred, a fine painter herself, first made Mondrian’s acquaintance in Paris in 1934. Indeed in 1935 Winifred was the first English purchaser of a Mondrian (he was already in collections in America), the masterly Composition with Double Line and Yellow, 1932 (pictured below), which was also the first Mondrian to use a double line: its vibrancy still startles.

The friendship further deepened when Nicholson facilitated his colleague’s move from Paris to London in 1938, in effect rescuing him from the Continent. Mondrian, understandably concerned about the political situation in general and his own position in particular (he had featured in Hitler’s notorious Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich in 1937) left his austere studio in Paris and joined the so-called "nest of gentle artists" - of course they were anything but – in Hampstead, which included not only Nicholson but Henry Moore and Naum Gabo. There too was Barbara Hepworth, already Nicholson’s lover and soon to be his second wife. Mondrian had brought his jazz records – he adored dancing – and his unfinished paintings, and set to work.

The friendship further deepened when Nicholson facilitated his colleague’s move from Paris to London in 1938, in effect rescuing him from the Continent. Mondrian, understandably concerned about the political situation in general and his own position in particular (he had featured in Hitler’s notorious Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich in 1937) left his austere studio in Paris and joined the so-called "nest of gentle artists" - of course they were anything but – in Hampstead, which included not only Nicholson but Henry Moore and Naum Gabo. There too was Barbara Hepworth, already Nicholson’s lover and soon to be his second wife. Mondrian had brought his jazz records – he adored dancing – and his unfinished paintings, and set to work.

Nicholson’s paintings deploy overlapping planes of relatively soft colours, with a sense of three dimensions, of recessive space. His carved white wooden reliefs sensitively use shadow to suggest line with light. Nicholson’s paintings and reliefs are refined, elegant, pleasing meditations on shape and colour. Mondrian too is pared down, resolutely flat, the paintings anchored by brilliant, punchy primary colours, suspended in an infrastructure of bold black lines, white always as the field. The Nicholsons have a charm that is almost delicate. The Mondrians are striking statements, shape and colour poised in dynamic equilibrium; their rightness of shape, colour, structure is dazzling, their energy after 70 years undimmed. Nicholson’s adventure was to strip out all reference to the observed world; but Mondrian invented a convincing and lasting vision, with an impact that is still reverberating. Who’s afraid of red, yellow and blue? Not Mondrian - he made them his own.

When war came, the Nicholsons went to St Ives in Cornwall but Mondrian, urban to the last, headed for New York, missing London but energised by the new world. His late masterpieces were New York Boogie-Woogie and Victory Boogie-Woogie, the latter still unfinished at the time of his death in 1944.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment